The neuroscientific revolution is erasing the line drawn between disorders of structure and function. Medical fields were defined on the basis of what could be seen with the naked eye or with a microscope at autopsy. With advanced brain imaging, neurophysiological techniques, sophisticated animal models, and cell cultures, it has become apparent that

all brain disorders have their basis in brain structure and that

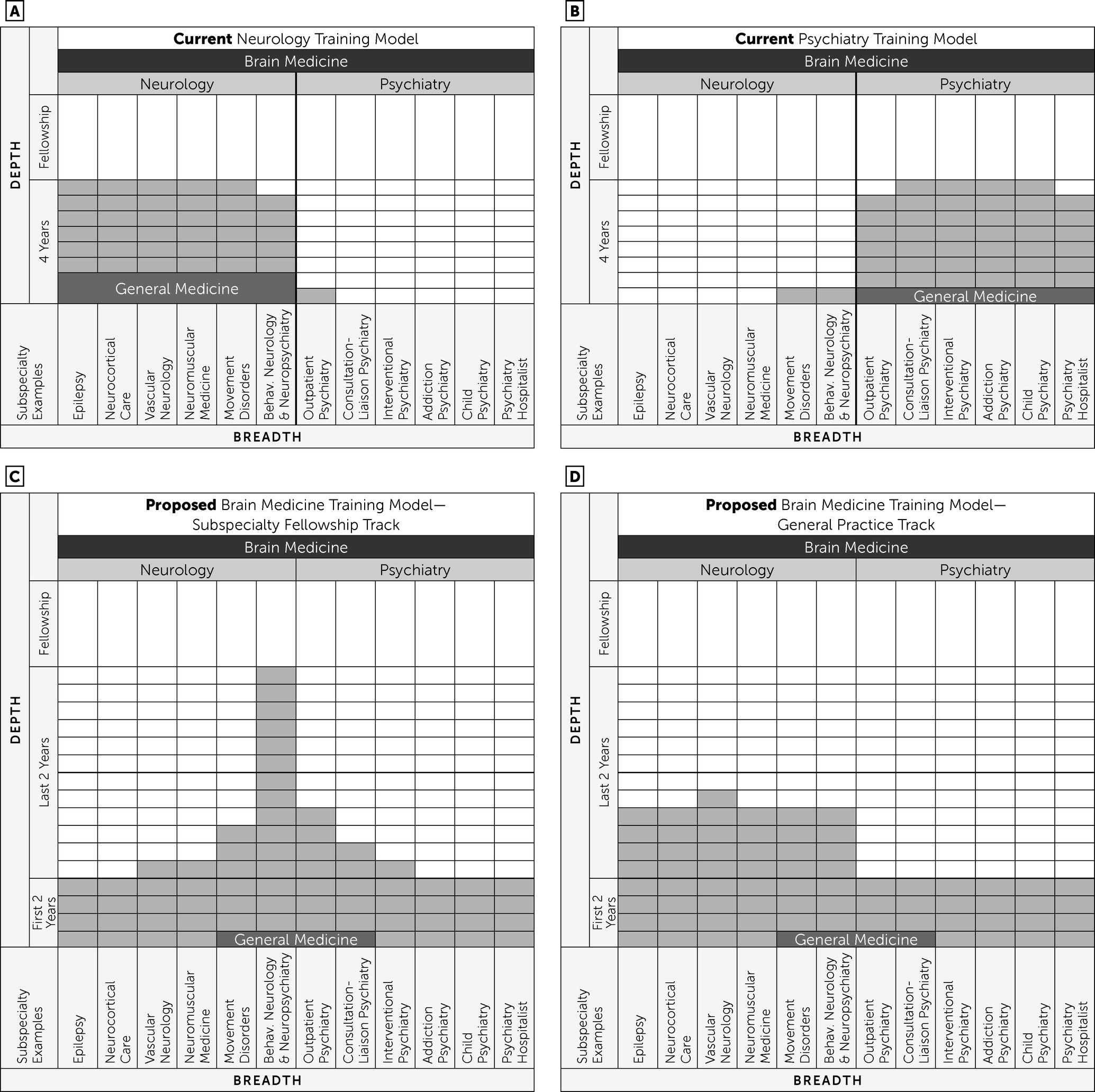

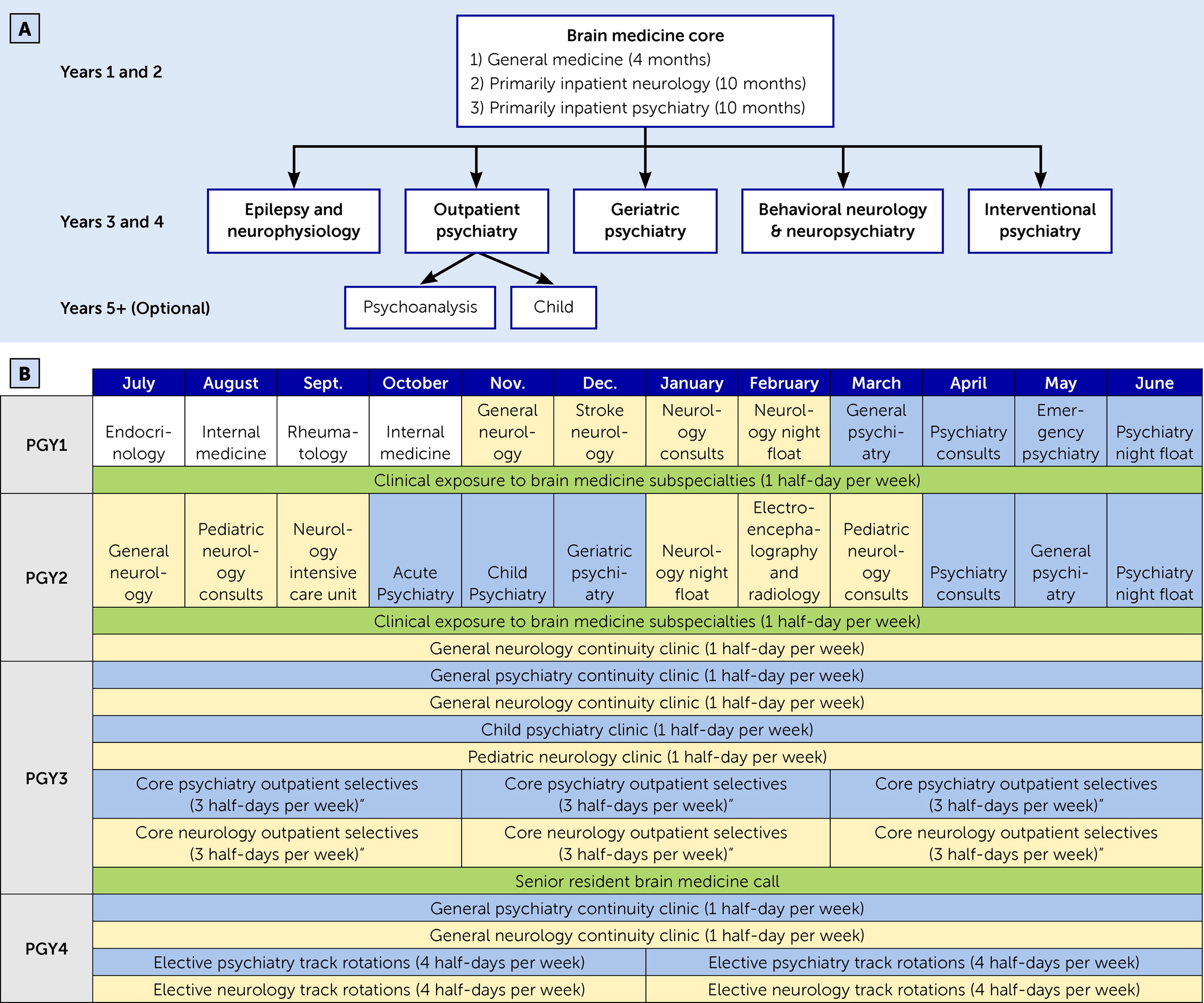

all brain disorders affect brain function. However, clinical training remains stuck behind these boundaries. In response, we propose a novel residency program to address the growing need to provide training that captures the multifaceted nature of the brain—with flexibility for early subspecialization to keep up with advances—without increasing the duration of training. This is accomplished through foundational training in brain medicine during the first 2 years, followed by 2 years of subspecialization or more extensive generalization (

Figure 1C–D).

Although we are proposing this as a novel training paradigm, it is actually not new at all. Internal medicine residents become board eligible after 3 years of training across organ systems, followed by optional subspecialization. The proposed brain medicine training program would mirror this paradigm, except that trainees would complete all 4 years before board eligibility. We will now address several notable challenges and limitations.

Competency in Only 4 Years

Time in training is a precious commodity. In an era of reduced resident work hours, bloated electronic medical records, increasing regulatory requirements, and expanding medical knowledge and subspecialties, is it possible to train in two specialties without increasing the duration of training? Even our current single-specialty system grapples with attaining proficiency in the face of time limitations (

20,

21). How, then, can one possibly become competent in two specialties in only 4 years? We contend that it can be done through reprioritization. The brain medicine concept is not an accelerated program for the most gifted, nor is it a shortcut. Current combined neurology and psychiatry programs (in which all of the authors trained) reduce the combined 8 years of training into 6 years through overlapping shared requirements and not duplicating the intern year. In the proposed brain medicine program, as illustrated in

Figure 1, several months of general medicine in the first year are reallocated to brain medicine. Furthermore, once a senior-resident level of competency is attained, various rotations less critical to one’s chosen field are reallocated and dedicated toward one’s chosen subspecialty (

Figure 1).

We concede that achieving expertise in all brain subspecialties in 4 years is not possible. We contend that because subspecialists are increasingly practicing only within their subspecialty, it is not necessary to spend precious months of training in less relevant subspecialties. Even now, there are more subspecialties than there are months to rotate through them. The trend toward subspecialization is a product of the incredible expansion of knowledge in this last frontier of neuroscience. As a result, a misguided goal to maintain a traditionally accepted ratio of individual knowledge to available knowledge in one’s specialty (as a metric of competence) established 80 years ago could arguably result in a 30-year program today. It is therefore an untenable position to strive for the same depth across the entire breadth without continuously increasing training duration. Rather, creative solutions to the already restrictive time limitations must be conceived and implemented (

22).

In current practice, a stroke specialist typically does not manage patients with new seizure onset or read the electroencephalogram, but rather he or she consults the epileptologist. After years of practicing only within one’s subspecialty, those skills not actively in use will fade. With this inherent reality in mind, what should be the goal of training? Is it to be capable of fully managing every patient (which is not currently accomplished), or is it to develop expertise in one’s subspecialty while appropriately referring with awareness of urgent issues, initial work-up, and treatment? This is the level of competency expected of a senior resident, which is currently supposed to be accomplished after 2 years of training. Brain medicine, therefore, is a deliberate shift from trying to become expert in all subspecialties to gaining a senior-resident level of competence and familiarity across aspects of the brain, followed by focused training related to one’s subspecialty. Currently, decisions of subspecialty are typically made in the third year, which would fit within the time frame of the proposed brain medicine program (

Figure 1).

We have focused on subspecialties to this point, but neurologists and psychiatrists who have a more general practice constitute many of those in the two fields and are critical to the public health mission. Brain medicine easily incorporates training programs that remain broad (

Figure 1D) and can be favorably compared with current structures (

Figure 1A) but with an additional foundation that covers aspects of the whole brain. In this sense, brain medicine training is broad: it is more akin to internal medicine training than the narrow subspecialty of behavioral neurology & neuropsychiatry, for which combined neurology and psychiatry training is often confused.

It is worth emphasizing that in only 3 years, our internal medicine colleagues develop the clinical competence to diagnose and treat disease across all other organ systems and are actually board eligible without any required fellowship training. Our internal medicine colleagues are well respected and competent. Similar to the situation with internal medicine, all current neurology and psychiatry subspecialties would be available through brain medicine. Both fields are already governed by the same board, the ABPN, and there is already substantial overlap in tested material. We can also look to other combined programs: internal medicine-pediatrics programs combine two 3-year specialties into a 4-year program. Adding only one extra year is achieved through substantial overlap. By contrast, combining fields that merely intersect, such as child neurology, leading to board eligibility in pediatrics and neurology, as well as triple-board programs, leading to board eligibility in pediatrics, psychiatry, and child psychiatry, are both 5-year programs. Both add only 1 year to the standard 4 years of neurology or psychiatry despite only intersecting knowledge and practice bases. This raises the question of whether psychiatry and neurology have enough overlap (a single-organ system) to be accomplished in 4 years through the proposed changes described herein or whether, like the combined programs above, an additional year will be necessary.

With our collective experience from combined neurology and psychiatry training, we believe that 4 years may be sufficient to accomplish our stated goals of training, with additional expertise still available through fellowships. However, this is merely our opinion. We are proposing an idea that must be tested before it can be considered for widespread implementation. Trials and testing may reveal that 5 years is needed to achieve competence in brain medicine. The important consideration is that both 4-year and 5-year programs are tested, with detailed outcomes of competency and feasibility being assessed. Only then can the optimal length of a curriculum never before attempted be known with any certainty.

Our field is changing and requires a fresh view. For example, fellowship training may expand to include modes of practice, similar to existing nonapproved neurohospitalist fellowships or interventional psychiatry fellowships (

23–

25). Brain medicine provides the flexibility to focus on the most relevant training (

Figure 1) while coming to understand manifestations of the whole brain.

Implementation

Change is challenging. How can a change of this magnitude actually be implemented? The first–and arguably most important–point is that we are proposing a change in residency training but

not in departmental structure or clinical practice models. In other words, while this training model allows for change in response to neuroscientific advances to improve patient care, the only direct change is in residency rotations. Leaving most of the current infrastructure intact is an advantage of the brain medicine training model and may help facilitate this experiment. None of the following would have to be changed: ACGME requirements, trainee competencies, ABPN board-certification examinations, existing clinics and services, faculty positions, promotion structures, and so forth. The difference comes not in

what physicians practice but in

how we practice and, ultimately, in

how well we practice. As an example, if a patient is seeking a movement specialist, he or she will be referred to a movement specialist in a neurology department. The difference will be that this movement specialist would have a greater background in psychiatry from the first 2 years of training, with which to manage comorbid conditions and more keenly recommend medication changes if iatrogenic contributions are recognized. Additionally, this movement specialist would have had increased exposure to his or her chosen subspecialty before a fellowship (

Figure 1). The individual would otherwise be hired and promoted exactly as he or she would in the current structure.

All of this being the case, changing a residency structure is not trivial. Multiple levels of stakeholders have vested interests in these programs and must be included in the process of actually implementing brain medicine: the ACGME and its Review and Recognition Committee over neurology and psychiatry; the ABPN as the governing board for both specialties; and governing entities of both specialties, which include the American Psychiatric Association, the Association of University Professors of Neurology, the American Academy of Neurology, and the American Neurological Association. Change is difficult, and change should not be made only for the sake of change. The benefits of a brain medicine training program must prove beneficial in smaller pilot programs before widespread support is solicited.

The ACGME has a platform for novel pilot residency programs (

26). Thus, a stepwise integration “where the rubber meets the road” is possible and appropriate. We expect that the model would be tested before full-scale implementation. It would likely start with a resident from one program, then another, then perhaps a small cohort, then numerous cohorts, and so forth. As with all things, the idea must be tested, and if it proves to be superior and feasible, it will naturally emerge as the predominant training paradigm. As it is in science, a novel idea may begin with a single subject before larger studies are warranted and before eventual widespread acceptance, if merited. One such scientific example of this principle comes from one of the authors of the present article (M.S.G.) (

27).