For New Yorkers, there will be “no wrong door” when seeking health care—primary care, mental health care (including substance abuse treatment), or any other specialized care—at state-operated health facilities.

The state has made a full commitment to the principles of integrated care in public-health facilities, including monitoring of mental health conditions (starting with depression) in primary care (as well as of key general health indicators in mental health care settings). This also includes providing incentives for adoption of the “collaborative care” model at primary care training clinics at selected academic medical centers, and Medicaid reform by taking advantage of the Medicaid health-home option in the Affordable Care Act.

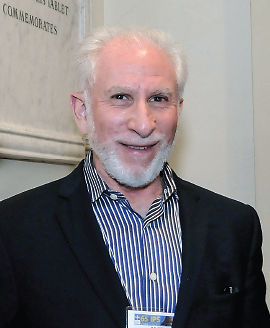

Lloyd Sederer, M.D., medical director of the New York State Office of Mental Health (OMH), said that together, these initiatives represent what may be the most far-reaching effort by a state mental health authority to move toward an accountable and more fully integrated 21st-century public-health delivery system.

“From the start since I came on at OMH, we have made integrated care a guiding principle,” Sederer told Psychiatric News. “Beginning with the integration of mental health and substance abuse treatment and later the integration and coordination of mental health and primary care, we are building integrated care into clinical care, step by step, throughout the state.

“The idea is that for patients there will be no wrong door for them to enter to get the health care they need, whether they are seen at a primary care or a behavioral health clinic,” he said.

In a state like New York, the task is enormous—the OMH licenses and oversees mental health services provided to more than 700,000 individuals each year by more than 100 not-for-profit hospitals, 80 assertive community treatment teams, and 250 agencies offering clinic and other ambulatory programs. The state also operates 24 state psychiatric hospitals and more than 90 outpatient clinics.

In a column in the September Psychiatric Services, Sederer and coauthors Thomas Smith, M.D., and Matthew Erlich, M.D., described the pressing fiscal case for integrated care. “In 2009 total Medicaid expenditures in NYS [New York state] exceeded $54 billion, including $7 billion spent on individuals with behavioral health conditions,” they wrote. “As in other states, Medicaid is a ‘budget buster,’ and in 2011 NYS Gov. Andrew Cuomo convened a Medicaid Redesign Team to provide recommendations for restructuring the state’s Medicaid program. More than 800,000 individuals were identified as the most costly, indicating both that expenditures were not under effective control and that the health of these individuals was poorly managed. Over 50 percent of these individuals had a primary or secondary behavioral health diagnosis.”

Speaking with Psychiatric News, Sederer credited the leadership of former NYS Mental Health Commissioner Michael Hogan, Ph.D., in championing integration and current Health Commissioner Nirav Shah, M.D., in continuing the effort. It was Hogan who encouraged Sederer to expand statewide the primary care initiatives he had helped start in New York City, when he was executive deputy commissioner for mental hygiene in the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. For instance, in 2005 an initiative was undertaken in the city to get primary care practices to use the PHQ-9 on a routine basis to screen for and then treat depression. The project included the municipal hospitals, which serve 1 in 8 New Yorkers, as well as other major hospital settings (Psychiatric News, May 20, 2005).

In the early phases of integration at the state level, the focus was on bringing together mental health and substance abuse treatment. Beginning in 2007, OMH and the Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services, along with the New York State Health Foundation, began collaborating on ways to integrate treatment of people with co-occurring disorders.

The state agencies removed financial and regulatory barriers to integrated treatment, and the foundation provided funding to establish a Center for Excellence in Integrated Care; the goal has been to provide hands-on assistance in implementing best practices in at least half of the state’s 1,200 mental health and substance abuse treatment clinics. The effort is described in the October Health Affairs in the article “New York State Health Foundation: Integrating Mental Health and Substance Abuse Care.”

Then, in 2009, OMH required monitoring of cardiometabolic status and antipsychotic prescribing in all state-operated mental health facilities for adults, youth, and forensic populations. This involved establishing standards for quarterly electronic reporting of blood pressure, body mass index, and smoking status for all adults (and slightly different metrics for youth) in state-operated outpatient settings.

A recent review of approximately 4,000 NYS OMH adult inpatients also showed that cholesterol levels dropped over time and that levels were significantly lower than the national norm for this population, even when adjusted for age.

And last year, OMH partnered with the NYS Department of Health to implement collaborative care—based on the model developed by Jürgen Unützer, M.D., and Wayne Katon, M.D., at the University of Washington—at primary care training clinics at 20 academic medical centers statewide. The initiative will train primary care providers to screen for and treat depression, using care managers to engage and educate individuals, and psychiatrists will be available to consult with care managers and primary care doctors regarding individuals whose depression-assessment scores show little improvement.

“The project has the additional benefit of introducing a new generation of physician trainees to the principles of collaborative care,” Sederer told Psychiatric News, a step toward remaking the culture of medicine in the future.

That’s crucial, because as Sederer and colleagues wrote in Psychiatric Services, “Integrated health care is the new gold standard” for individuals with general medical and mental disorders, whether their medical home is a primary care clinic or a community mental health center.

“When a ‘no wrong door’ policy is in place, individuals need not (and will not) seek different settings for detection and routine treatment of highly prevalent general medical and mental disorders,” they wrote. “Integration, therefore, opens the door to collaboration, timely care, improved quality, and parity for general medical and behavioral illnesses—and closes the door on disconnected treatment that is divisive, ineffective, and inaccessible.” ■