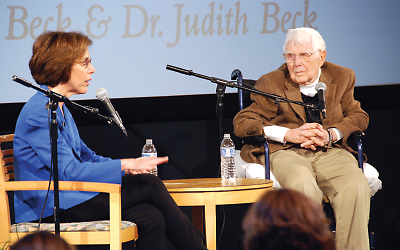

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) reshaped the field of psychotherapy over the last several decades, and in November in Philadelphia, Aaron Beck, M.D., who developed the therapy, discussed its origins and growth in a dual interview with his daughter and colleague, Judith Beck, Ph.D.

Beck developed CBT in the 1960s at the University of Pennsylvania at least partly in reaction to the then-reigning psychoanalytic paradigm.

“We changed therapy by emphasizing current problems, as opposed to childhood experiences,” said Aaron Beck before a large audience in the studios of public radio station WHYY. “Therapy today is more structured, with more activity by the therapist compared to analysis, and more emphasis on coping by the patient.”

Beck graduated from Yale Medical School in 1946. Today, at age 92, he is professor emeritus of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and president emeritus of the Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

Like most of his generation, Beck began his career as a psychoanalyst. In analytic theory, dreams were said to reveal the patient’s inner state, yet Beck’s clinical experience convinced him that the dreams of depressed patients were quite benign.

“But their self-image affected the way they viewed the world,” he said. “A negative self-image screened out the positive things in their lives.”

When sitting opposite his patients, he observed the expression of emotions on their faces and thus could ask what they were thinking about at that moment. “I saw their expressions as automatic thoughts, a form of internal communication not usually said out loud,” he recalled. At that moment, he asked his patients to pin down the negative thoughts they had just before sensing the emotion. He then began actively challenging the patients’ statements, asking them for the facts behind their words.

“CBT is about the problems connected to the reactions to an event, not to the event itself,” said Judith Beck, a clinical associate professor of psychology in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and president of the Beck Institute.

“People in psychological distress often have a distorted view of their situation,” she said. “To make lasting changes, you have to work at deeper levels of core beliefs.”

Despite the name, cognitive-behavior therapy is not defined solely by cognitive techniques, she pointed out. Therapists can also use psychodynamic techniques, gestalt therapy, supportive methods, medication, or environmental change.

Fidelity to the CBT model is important, though, she said. The Becks have long conducted research to validate CBT, and in 1994 they created the Beck Institute as a center for training clinicians in this modality. Aaron Beck still takes part in training programs there.

“Cognitive-behavior therapy is practiced more outside the United States than here,” he said. In Britain, for instance, the institute has trained more than 8,000 clinicians who have helped more than 1 million patients, he noted.

Trainees anywhere in the world can now upload tapes of patient sessions and get an hour of consultation and supervision.

However clinicians learn CBT, the essence of the process remains the structure of the patient-therapist interaction, said Judith Beck.

Ideally, a session begins with a preparatory discussion with the patient, choosing and prioritizing one or two problems. After discussing those points the therapist asks the patient to summarize the session and then agree to some action or homework before the next session. Finally, the therapist asks the patient for feedback, making therapy a collaborative enterprise.

“Our goal is to teach patients to be their own therapists,” she said.■