Thanks to the exciting new field of neuroimaging in psychiatric genetics, it may be possible eventually to identify people who are at risk of Alzheimer’s disease soon after birth.

Rebecca Knickmeyer, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, and her colleagues have not only identified in newborns the Alzheimer risk gene variant APOE-e4, but have linked its presence with reduced temporal cortex volume, which is also known to be present in adults with the APOE-e4 variant.

These findings were published January 3 in Cerebral Cortex.

But other provocative results emerged from their research as well.

The study included 272 Caucasian infants who received MRI brain scans at University of North Carolina–affiliated hospitals shortly after birth. The DNA of each newborn was tested for common variations in seven genes that have been implicated in various psychiatric illnesses—Alzheimer’s, autism, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, and schizophrenia—and that have been associated with brain abnormalities in adults. The genes are DISC1, COMT, NRG1, APOE, ESR1, BGNF, and GAD1. The researchers then assessed whether any of these variants could be linked with brain abnormalities in the newborns.

They did in fact find such an association, and not just for the APOE-e4 variant, but for other variants as well.

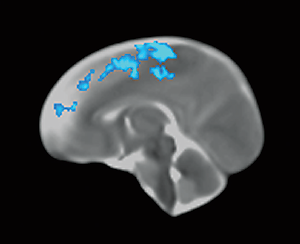

For example, newborns who had two copies of a particular variant of the DISC1 gene—the rs821616 variant—had reduced gray matter in their frontal lobes, especially in the medial superior frontal gyrus and motor areas as well as in the lateral temporal cortex including the superior and middle temporal gyri. Reduced volumes in the medial superior frontal gyrus have been reported in young adults with two copies of this variant. Also, gray-matter reductions in the superior temporal gyri have been noted in individuals with schizophrenia.

Newborns who had two copies of a variant of the COMT gene—the rs4680 variant—had reduced gray matter in their temporal lobes, especially the hippocampus. Such alterations have also been frequently observed in individuals with schizophrenia.

“Our results suggest that variation in COMT affects neural systems implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia before birth,” Knickmeyer and her colleagues said.

Thus “common genetic polymorphisms in putative psychiatric risk genes predict individual differences in brain structure shortly after birth,” the researchers concluded. “These variants and the associated neuroimaging phenotypes likely represent stable markers of risk and highlight the critical role of the perinatal period in the etiology of mental illness.”

In an accompanying press release, Knickmeyer said that her group’s study results “could stimulate an exciting new line of research focused on preventing onset of illness through very early intervention in at-risk individuals.”

“This fascinating study indicates that genes that increase risk for some psychiatric diseases may actually alter brain structure prior to birth,” Gary Small, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, and a neuroimaging and Alzheimer’s expert, said in an interview. “These findings point to the importance of developing interventions that exert their effects very early in the course of these conditions so that they can protect a healthy brain before neuronal damage becomes extensive.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. ■