The theory that psychotic disorders are caused by infection went for decades without receiving more than an occasional raised eyebrow from researchers, but new studies have revived interest in its validity. If the theory turns out to be correct, psychiatry could begin to find cures in antimicrobials.

The prime suspect is Toxoplasma gondii, a protozoan parasite carried primarily by cats.

“When we started, it was considered a crazy idea,” psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey, M.D., executive director of the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI), told Psychiatric News. In the early 1970s, Torrey began to suspect an infectious origin of schizophrenia. He has been on this trail for decades.

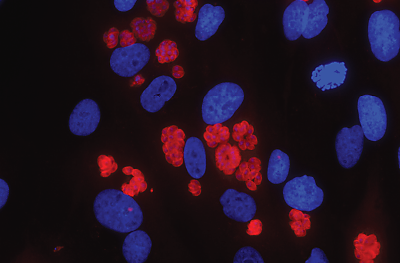

Torrey does not have direct evidence to convict T. gondii as the culprit, but quite a bit of circumstantial evidence exists. For one, T. gondii, in its dormant form as cysts, is known to invade brain tissue in humans and remain there for as long as the person lives.

Second, congenital infection with T. gondii is known to cause brain abnormalities, including mental retardation, deafness, and seizures in the fetus. This is why pregnant women are routinely tested for T. gondii antibody, a sign of infection or past exposure, and are warned against handling cat litter.

Third, epidemiological data from Eastern Europe and Asia for over a half century have consistently shown that a T. gondii-positive test is more common in those with schizophrenia than in the general population.

Another piece of the evidence puzzle is that T. gondii can manufacture dopamine. “We know toxoplasma has the genes to produce a precursor of dopamine,” said Torrey. Excess dopamine in the brain has long been associated with psychosis. “This idea that excess dopamine [in schizophrenia] may be coming from an outside organism is kind of mind-blowing,” he said, marveling at the “smart little organism.”

Besides dopamine, T. gondii may also cause human nerve cells to secret GABA, another neurotransmitter, according to a study by researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and published online in PLoS Pathogens December 6, 2012.

“[The cysts] are not replicating in the brain, but they do appear to be active in some way,” Robert Yolken, M.D., a professor of pediatric infectious disease at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) Medical School, told Psychiatric News. An expert in infectious diseases, he has been a long-term research collaborator of Torrey’s. Yolken heads the developmental neurovirology lab at JHU. In addition to producing neurotransmitters, the parasite may manipulate brain functions by inducing an autoimmune response, he suspects.

Infection Theory Long Ignored

Despite the slowly accumulating findings supporting the infection theory, it has been unable to penetrate mainstream psychiatric research. Torrey believes that’s because the theory does not fit into preexisting paradigms of psychiatric disorders. “There are ‘fashions’ in scientific research, and the fashion in psychiatric research for many years has been genetics and neurotransmitters,” he said. “Things that fall outside the fashions are basically ignored.”

Yet genomic studies have failed to identify genes that can explain schizophrenia. Curiously, the chromosome region that has come up repeatedly in association with schizophrenia is the HLA genes involved in immune response, Torrey noted, which again points to a possible infectious element in the pathology.

Perhaps it is not surprising that the infection theory has gotten little notice. After all, it is difficult for humans to imagine that their brain, self-regarded as the most complex organ in the natural world, can be so easily hijacked by a primitive single-cell organism. Also, noncongenital T. gondii infection causes no overt psychiatric symptoms in humans.

However, scientists know that the parasite alters mouse behaviors in subtle and strange ways. For example, mice infected with T. gondii, which is shed in cats’ feces, become bolder and lose their natural fear of the smell of cat urine. This phenomenon makes sense, as a mouse not afraid of cats is more likely to be eaten by cats, thus allowing the T. gondii cysts to reinfect the primary host, cats, and completing its lifecycle.

Like mice, humans can become a secondary host, usually through ingesting undercooked meat or contaminated water. Research on what T. gondii does to humans has been mostly done by biologist Jaroslav Flegr at Charles University in Prague. He has shown that men who have been infected by toxoplasma are more suspicious, jealous, and impulsive than men who have not been infected, but women with the infection tend to show more warmth and sociability. He also found that toxoplasma-positive individuals have a higher risk of causing motor-vehicle accidents. Torrey thinks Flegr’s research is intriguing and credible but “needs replication.”

Probably a Predisposing Factor

The prevalence of T. gondii has been estimated at 20 percent to 30 percent in the U.S. population. Therefore, it cannot be a sufficient cause for schizophrenia. “Genetic predisposition is a possible factor,” Torrey suggested, citing the link between HLA genes and schizophrenia. Different strains may have different effects on the infected individual. “We know some strains are more lethal than others,” he noted. In addition, Yolken proposed that the timing of toxoplasmosis may be important. Perhaps schizophrenia would occur only in those with early-in-life infection by certain virulent strains.

When pressed for his own beliefs, Torrey said he is convinced T. gondii is “one etiological factor in a majority of cases of schizophrenia.”

T. gondii has been suspected of increasing the risk of bipolar disorder with psychotic features and suicide (Psychiatric News, January 4).

For decades, SMRI has been the major funding source for research on infection as a cause for psychotic disorders. Recently, however, more researchers have joined the quest. In addition to the Swedish researchers, a group of French researchers published a study on human endogenous retrovirus type-W and schizophrenia in the December 4, 2012, Translational Psychiatry. The retrovirus is incorporated into the human genome and can be passed to offspring. The authors found greater transcription of the viral envelope protein in schizophrenia and bipolar patients than in healthy controls, as well as an association between the viral transcription and T. gondii exposure.

“Now we’re almost respectable,” Torrey said with a chuckle.

Experimental Treatment May Prove Case

“Ultimately no one is going to believe our theory until you can show that, if you treat a [schizophrenia] patient with antitoxoplasma treatment, the person improves,” said Torrey. The hurdle is that antitoxoplasma drugs were discovered to treat malaria and are barely effective against T. gondii, especially in the dormant stage. Crossing the blood-brain barrier to reach cysts in the brain poses additional difficulty.

Torrey and Yolken have identified a candidate drug originally developed for malaria and have high hopes for its viability. The yet-unnamed drug is effective in killing T. gondii cysts in mice and is in preclinical development in preparation for human testing.

Meanwhile, Yolken, who owns two cats, recommends people handle cat litter with care and keep cats indoors as much as possible. ■