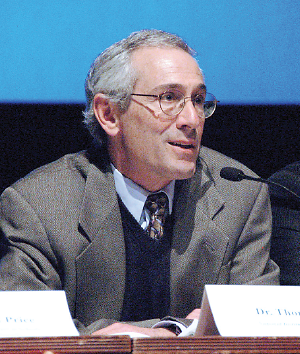

The popular association of homicidal violence and mental illness is tenuous at best, Thomas Insel, M.D., director of the National Institute of Mental Health, pointed out to congressional staff members at a Capitol Hill briefing in late January.

“Suicide, not homicide, is the most urgent public-health problem associated with gun violence,” said Insel. About 90 percent of suicides involved individuals with mental illness, but that was true for only 5 percent of homicides.

The briefing was one of several held in the wake of the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. The session on mental health aspects of gun violence prevention was led by Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) and Rep. Grace Napolitano (D-Calif.), chair and co-chair, respectively, of the House Democratic Gun Violence Prevention Task Force.

Despite common public perceptions, there is little connection between gun violence and mental illness, said Insel. Only 6 percent of violent crimes were committed by someone with a diagnosed mental illness.

However, certain subgroups presented higher than average risks, he pointed out.

The approximately 100,000 people (most of them aged 16 to 20) who become newly psychotic each year but who are not diagnosed or being treated are at increased risk of violence, he said. “About 38 percent of those within or before a first episode of schizophrenia may become violent,” he said. “But once they are treated, the rate of violence decreases 15-fold.”

Furthermore, people with mental illness were 11 times more likely to be victims of violence than its perpetrators, he noted. “We can do better if we get involved sooner with early detection and early intervention.”

“Behavioral health, mental illness, and substance abuse are not social problems,” added Pamela Hyde, J.D., administrator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. “They are public-health problems and should be tackled and solved that way.”

Napolitano and Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.) told the briefing that they will introduce the Mental Health in the Schools Act in the House and Senate, respectively. (At press time, both had introduced the bill in their respective chambers.) The proposed act would provide resources for schools to work with mental health care providers and offer comprehensive training to parents and teachers about warning signs of mental illness, said Franken.

“It’s not just about preventing violence,” he said. “It’s about making sure kids have access to mental health services.”

Napolitano has introduced similar legislation in previous sessions of Congress, but the program she has advocated has received only pilot-stage funding. She said she is concerned that fiscal wrangles in Congress lie in the way of final passage.

“Unless we find the money, the likelihood of passage is quite low,” she told Psychiatric News after the briefing.

Nevertheless, she and other speakers said that the tragic shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School might spur action to reduce gun violence and increase access to mental health services for young people.

Insel also sought to inform his audience about the biological substrate of mental illnesses, which should be viewed as disorders of brain circuitry, he said. “We should be rethinking how we talk about these disorders.”

He added that “the behavioral changes occur before the first changes are observable in the brain itself.”

Early detection and intervention have reduced morbidity and mortality in other illnesses, he emphasized. “Science can transform the way we think about these disorders, too.” ■