This article is the first in what Psychiatric News

hopes to be a series for the Residents’ Forum in which residents write about a mentor or psychiatrist who made a deep impression on them or influenced their career path. More information is available by contacting Catherine Brown at [email protected] . When Dr. Benjamin Liptzin arrived at McLean Hospital in 1978 to direct the geriatric unit, his 92-year-old patient had already been there 60 consecutive years. When she died at age 102, she had stayed on the unit for 70 years! “Her hospital course reflected the whole of 20th-century psychiatry,” recalled Dr. Liptzin. Looking back, he wondered if he should have discharged her to a nursing home. She had been stable, and her hallucinations were relatively quiet. “It just didn’t feel right to discharge her after so many years, and we wondered how much longer she would live.”

Geriatric psychiatry as a specialty did not exist until the late 1970s. At McLean, Dr. Liptzin started one of the first geriatric psychiatry fellowships in the country. “It was an exciting time for geriatric psychiatry,” said Dr. Liptzin. Anyone over age 65 had Medicare for health insurance, and many were in need of services and more willing to accept those services. He recalled that you could tell the population was changing because elementary schools were turning into senior centers.

Dr. Liptzin turned the geriatric unit at McLean into a more contemporary, shorter-stay unit. He came from humble beginnings, but he seemed destined to be a psychiatrist. Born in the Bronx, Dr. Liptzin was the youngest of three children. Loving science and math, he attended the prestigious Bronx High School of Science. His older brother was already in a psychiatry residency at Rochester when he was 15 years old. One summer, Dr. Liptzin borrowed one of his brother’s books by Erik Erikson and read it when he was a camp counselor. Dr. Liptzin majored in developmental psychology at Yale College and matriculated at the University of Rochester for medical school. He did his psychiatry residency at the University of Virginia.

After residency, he worked for the Public Health Service at the National Institutes of Health for several years and became a consultant for the care of elderly patients in Washington, D.C.

It was during this time that he fell in love with geriatric psychiatry. He recalls one time in which he treated an older woman who was depressed, grimacing in pain, and wanting to jump off a roof. After having been prescribed an antidepressant medication, she no longer felt depressed and her functioning dramatically improved. She wore make up again and even volunteered at a nursing home, he recalled. While in Washington, D.C., Dr. Liptzin served as a Ginsburg fellow at the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry (GAP), producing manuscripts for the Preventive Psychiatry Committee that would help shape the future of psychiatry.

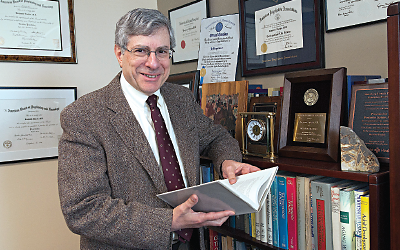

Forty years later, our paths would cross, and I would be in the same position as a Ginsburg fellow, but for the Committee on Aging, which Dr. Liptzin chairs. His current title is chair of psychiatry at Baystate Medical Center and professor and deputy chair of Tufts University Department of Psychiatry.

Over the years, Dr. Liptzin has contributed seminal papers in the field on delirium and health services research, and won numerous awards, including the Jack Weinberg Memorial Award for Geriatric Psychiatry from APA. He has held prominent positions in APA, the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, and the International Psycho-geriatric Association.

The current GAP Committee on Aging has experienced geriatric psychiatrists, such as Dr. Liptzin, who have served as mentors for me. What has impressed me most about these psychiatrists is their thoughtfulness, sincerity, and sense of perspective. They were the ones at the very beginning who set the tone for the field and are now passing the torch to the next generation of geriatric psychiatrists. At our semiannual meetings, Dr. Liptzin has given me incredible support and advice on how to succeed in an academic career.

His advice to residents and early-career psychiatrists is the following: 1) make your interests known; 2) pursue opportunities and see where they take you; 3) try out new things; and 4) always be learning. Throughout his life, Dr. Liptzin’s guiding principles have been to “develop yourself but make contributions to society and organizations.” He reminds us that the field continues to change, but geriatric psychiatry will always be a broad-based specialty with numerous clinical, research, and educational opportunities. ■