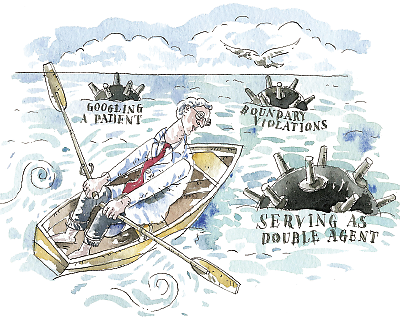

Psychiatrists have always been challenged about “doing the right thing” for their patients. And some of the same ethical hurdles that existed 30 years ago, such as boundary crossings, still exist today. But all things considered, the ethical landscape of today is quite different from that of that era, members of the APA Ethics Committee tend to concur.

For example, “Your primary job is to be the patient’s doctor,” Richard Milone, M.D., an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at New York Medical College and chair of the APA Ethics Committee, pointed out. “Any time you start being something else to a patient, it’s the start of trouble. What are some of the other things? Lending a patient money. You are not the patient’s banker. Borrowing money from your patient. The patient is not your banker. We’ve had psychiatrists who asked recently, ‘Can I be a guardian for a patient who is not thoroughly competent? He likes me; I like him.’ Well, you can’t do that because as a guardian you would have the responsibility of doling out money and giving an allowance to the patient. And if he were dissatisfied with how much you gave him, it could erode your doctor-patient relationship.”

“An ethical issue I’m coping with right now are the recent changes in CPT codes,” Claire Zilber, M.D., a Denver, Colo., psychiatrist and an APA Ethics Committee member, commented “One insurance company is requesting a patient’s entire chart before it will pay for every visit by the patient. Although technically the company is allowed to do that under HIPAA, I don’t think that it’s ethical.”

The new CPT codes present yet another ethical dilemma, said Mark Komrad, M.D., an instructor in psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions and also an APA Ethics Committee member. “There are now so many nuances in coding. Spending just one extra minute or two with a patient can bring you to a whole new code, which could get more reimbursement for the patient or for you. Should you shift the encounter one minute to maximize reimbursement?”

Psychiatrists May Work as ‘Double Agents’

A new ethical quandary for psychiatrists has appeared in the wake of the Newtown, Conn., school shootings last December, Milone suggested, as psychiatrists in some situations will both serve their patients and protect society from dangerous patients. Or as Komrad put it, “Society expects us to be their protectors, to work as double agents.”

“It is a longstanding principle in psychiatry that when a patient presents a serious and imminent danger to either himself or others, the psychiatrist has the duty to report it,” Milone explained. “This is the well-known Tarasoff rule. We psychiatrists accept that, we’re comfortable with it, and we employ it without hesitation. But some states—for instance, New York and Connecticut—have now passed gun laws that say that when a psychiatrist or therapist believes that a patient is likely to engage in conduct that would render serious harm to self or others, then it is the psychiatrist’s or therapist’s duty to report that patient. Likely is much weaker than imminent.

We psychiatrists are therefore concerned [that these laws can lead to] overreporting and a breach of patient confidentiality. The New York State Psychiatric Association and the APA Council on Psychiatry and Law are grappling with this conflict we are facing.”

Yet the greatest ethical hurdles psychiatrists have to cross these days are posed by the new information technology and use of social media, Elissa Benedek, M.D., a former APA president, an adjunct professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, and a member of the APA Ethics Committee, asserted. She believes that psychiatrists are facing more ethical challenges than ever before because of such technology.

For example, when, if ever, should you use e-mail with your patients? To schedule appointments only, Milone contended, and that is all that he uses it for.

Is it ethical to defend your professional reputation online when patients have negative things to say about you on doctor-rating sites? “What appears on such sites is more likely to come from disgruntled patients,” Komrad remarked. “But how can doctors defend themselves within the bounds of preserving patient confidentiality? Would it be appropriate to ask patients to make positive comments about you to balance the negative comments?” Komrad thinks probably not.

And when, if ever, is it ethical to Google patients?

Not long ago, Milone said, a psychiatrist agreed to discount his fee for a patient who he believed didn’t have much money. Subsequently the psychiatrist Googled the patient to learn more about him and found out that he lived in a mansion. The psychiatrist was furious and confronted him about it. It turned out that he did live in the mansion, but in the basement, and worked for the owners to help pay his way through college.

“This is an example of how patient-targeted Googling can go awry and put you in a bad place,” Milone noted. “It is also an example of why members of the APA Ethics Committee generally discourage Googling patients.”

Yet if current technology presents ethical conundrums, future technological developments will probably present even more.

“One of the ethical concerns about the initial evaluation of a patient is that it takes place in a face-to-face situation,” said Stephen Scheiber, M.D., an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Northwestern University and an APA Ethics Committee member. “Well, that was great 20 years ago. But does face-to-face include Skyping a patient while you’re sitting in your office? These are things that are coming at us at a rapid pace, and I think it is going to accelerate. And we’ll need to make sure that ethical considerations are taken into account early rather than after the fact.”

In Malone’s opinion, psychiatrists will be increasingly pressured to conduct therapy via the Internet, and “they’ll need to resist it,” he said. ■