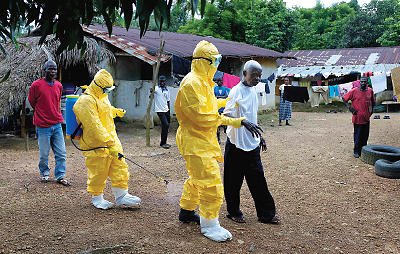

Hidden behind the scramble to halt the incendiary Ebola epidemic in West Africa are the early stages of efforts to deal with the inevitable psychological consequences of a major disaster.

Public health and infectious disease experts have already noted the weakness of the preexisting medical systems in the region.

“The Ebola crisis today is a reflection of long-standing and growing inequalities of access to basic health care,” wrote World Bank President Jim Yong Kim, M.D., and Paul Farmer, M.D., cofounders of Partners in Health, in the Washington Post on August 31. The nations hardest hit by the outbreak—Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—lacked the staff, supplies, and equipment to battle the disease, they said.

The same is even more true of the options for mental health care in those countries. Ebola has produced enlarging circles of victims beyond the infected and the dead. Survivors, families, children, and health workers are dealing with the stress and trauma left behind by the disease.

“The totality of the response has been quite slow, and the mental health response has even been slower,” wrote Benjamin Harris, M.D., in an email to Psychiatric News. Harris is an associate professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at A.M. Dogliotti College of Medicine in Monrovia, Liberia.

The only two internal medicine specialists in Liberia, including the head of the country’s only postgraduate medical training program, have died from the disease, he said

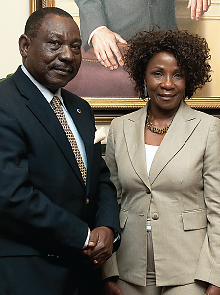

“There is a psychosocial burden of the disease on the families of health professionals,” said Mardia Stone, M.D., M.P.H., who returned from Liberia in August. Stone is an obstetrician/gynecologist and a senior advisor to the Chester M. Pierce, M.D., of the Division of Global Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. “Families are becoming quite resistant to having their loved ones go to work. Some people are even threatening to divorce their spouses. Nothing is being done to embrace the psychosocial element of what the workers are encountering.”

“[In Sierra Leone,] medical personnel are facing extremely long shifts attending to too many patients, with a lack of resources, while witnessing their colleagues’ deaths and working under lots of fear and stress,” said Carmen Valle, Ph.D., project coordinator and mental health specialist for the Enabling Access to Mental Health (EAMH) program in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in an email. EAMH is run by CBM, a Christian development organization based in Germany.

There is another vulnerable group, said Harris.

“Children made orphans by Ebola is a very sad and tragic consequence of the epidemic,” he said. “As a result of the increasingly widespread fear of infection, these children are being ostracized, stigmatized, and discriminated against, … partially driven by the low level of knowledge of disease transmission in the affected countries. Unless this situation is urgently addressed, these children will suffer adverse social and psychological consequences for years to come.”

In response, orphanages in Monrovia are starting to accept some children. Other groups are working to lessen stigma and reintegrate some of these children into their communities, he said.

In Sierra Leone, the Ministry of Social Welfare is working with child protection specialists from UNICEF and Save the Children to register “unaccompanied and separated children,” as they are termed, and find care for them.

EAMH is providing training and continuing support for child protection practitioners, as well as the services of mental health nurses, said Valle.

Access to mental health care was poor even before the epidemic struck and has been exacerbated by the trauma it is causing.

Sierra Leone has just one working psychiatrist, and there is one, small, aging psychiatric hospital in Freetown, the country’s capital, said Ayana Jordan, M.D., Ph.D., the chief resident in psychiatry at Yale. She has visited Sierra Leone frequently over the last four years, conducting psychiatric epidemiology surveys on behalf of the medical nonprofit Wellbody Alliance.

“Elsewhere in the countryside, there are no established mental health services,” said Jordan in an interview. “People with mood, psychotic, or substance abuse disorders are treated by traditional healers.”

The Ministry of Health and Sanitation issued its first mental health policy and strategic plan in 2012, said Valle. Since then, 21 mental health nurses have been trained and now work in district hospitals. Another 130 staff members at local clinics have been trained in basic metal health knowledge so that they can detect and refer patients.

Liberia faces similar conditions. “I am currently the only practicing psychiatrist in the country,” said Harris. “We have a small mental hospital that takes care of about 50 inpatients. Psychiatric drugs of all kinds are in very short supply, with shortages of basic drugs being faced on a regular basis.”

Given that background, any mental health response to the outbreak begins well behind the starting line, but at least it is beginning.

Before the outbreak, the Carter Center had helped train about 100 nurses and physician assistants in Liberia to assess and manage basic mental health conditions, said Harris. “I am not aware of any medical organizations providing mental health–related interventions currently in Liberia.”

The Mano River Union, a consortium of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, is developing a psychosocial initiative called the Social Protection Strategy, said Harris, who is working on the project. “Focus will be placed on minors, unaccompanied children, orphans, and widows.”

Stone expects a demand for psychiatrists and psychologists once the outbreak is under control, but foreign specialists will have trouble with local ethnic languages and cultural nuances even though the two countries’ official language is English.

EAMH and other organizations working in Sierra Leone are training health workers in psychological first aid and providing backup support to mental health nurses in district hospitals, said Valle. “The goal is to help them with stress-management techniques and referral to psychiatric nurses.”

A group of Sierra Leone expatriate mental health professionals is just beginning to organize to find ways to assist, Mandy Garber, M.D., of the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System told Psychiatric News. The use of quarantines and lockdowns to combat the spread of Ebola has meant that the few mental health workers cannot provide any individual therapy, so Garber’s colleagues are considering ways to use mass media like radio and television to provide some kind of relief.

As with any disaster, the greater part of the need for mental health evaluation and care will arise once the acute phase passes—whenever that might be. Stopping the virus is the great immediate priority.

“We need epidemiologists and other experts to help to minimize the spread of the infection in the various communities,” said Harris, praising the recent U.S. government decision to increase assistance.

“The main problem at this point is the lack of medical staff,” said Valle. “This outbreak is much bigger than we can control with the resources that we have. Many Sierra Leonean doctors and nurses are dying, and all the teams responding to the outbreak are overwhelmed and need more equipment, more isolation units, and more professionals.

“Unfortunately, mental health tends to come last in the provision of funds, and this outbreak is having terrible consequences in a population already affected by a cruel civil war. We are committed to work, we have wonderful Sierra Leonean staff, but we need as much support as possible.” ■

The website for CBM’s mental health program in Sierra Leone can be accessed

here. Two Boston-based nonprofits are working in the epidemic zone.

Wellbody Alliance trains community health workers and provides medical care in Kono, Sierra Leone;

Last Mile Health works in remoter villages in Liberia.