Though its impact can sometimes be underestimated, fatherhood is one of the most significant events in the life cycle of a man and is a major force behind the development of offspring. However, the ideals of fatherhood that were common a half a century ago may be forced to evolve with societal changes—at least for some cultures.

Last month, at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP) in San Diego, several psychiatrists of different ethnic and cultural backgrounds discussed their personal role in “modern” fatherhood and how it affects their children.

“Until the 1950s, fatherhood was [considered] patriarchal and colonial,” with autocratic characteristics and very little involvement with nurturing offspring, said Rama Rao Gogineni, M.D., division head of child and adolescent psychiatry at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University and chair of the session “Fatherhood: Sociocultural Clinical Considerations.”

With the current sociocultural evolution of fatherhood that is taking place, “we are beginning to understand the role of the father and his contribution to a child’s mental development,” he told Psychiatric News.

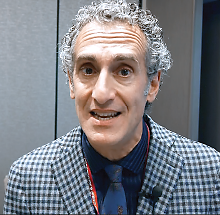

“Fathers in many ways provide the kind of structure and support of development that very much complement the nurturing role of mothers,” commented Andres Pumariega, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Cooper, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “They help solidify strong identity—especially as it relates to ethnic identity and racial identity.”

Pumariega, who is a Cuban-born American, focused on Latino fatherhood, the characteristics of which are being transformed in the United States by immigration and acculturation, he pointed out.

“The traditional role of Latino fatherhood is within the lines of machismo, which requires men to be strong, stoic, and protective,” he said. Though machismo is associated with family loyalty and sense of ethnic pride, Pumariega pointed out that the negative attributes of this ideology—including male dominance and gender-based double standards—can cause conflict in today’s assimilating Hispanic-American family.

“I have two daughters who are very outspoken and most certainly a part of the American culture,” he noted. “I started [fatherhood] in the machismo role. With new societal norms, I couldn’t be the overprotective father. My role had to shift as a nurturer, mentor, and advisor. … I had to learn how to collaborate more in parenting than just being the head, and it has worked well,” Pumariega said

“Fatherhood has become a huge part of my identity,” Peter Daniolos, M.D., training director of the adolescent and child psychiatry fellowship program at the University of Iowa Clinics and Hospital, told Psychiatric News. “My spouse, who is a ‘he,’ and I made a remarkable decision to become fathers … and it has been the most profound and powerful thing that I have ever done in my life—and also the most difficult.”

During his presentation, the father of two expressed that he never would have imagined that he would one day be leading a public discussion on such a topic.

“Growing up in Bismarck, North Dakota, there was absolutely no hope for marriage—or children—for a person like me. It was an extremely grim landscape for gays,” a once-common reality for many gay Americans who are now aged 50 and older, Daniolos explained. Due to recent legal protections granted in more than half of the states to gay men and lesbians, Daniolos said that youth who identify as such can expect both marriage and parenthood in their future.

Though some public-opinion polls have suggested that the majority of Americans have no problem with same-sex relationships, Daniolos said that he remains fearful for his children.

“Because homophobia is still prevalent … my fear [going into fatherhood] was that my children would be thought poorly of and would struggle with finding friends and playdates,” Daniolos said. He told Psychiatric News that he and his spouse are beginning to figure out ways to help their children respond when situations arise involving their children having same-sex parents without their children being distressed or alarmed.

“I think people meant well when they have asked me ‘Where is the mother?’ or asked my children ‘You have two dads?’ … These are all natural questions. Fortunately, these questions have not materialized into isolation or adverse consequences for my family. But as a father, I certainly have fears concerning how my children are perceived.”

Other topics addressed included becoming a father through adoption and the common negative perception of African-American fathers being absent in their children’s lives. In three recent high-profile cases involving confrontations with unarmed black youth (Trayvon Martin, Jordan Davis, and Michael Brown), very active and present fathers were fighting for justice for their sons, but these situations run counter to the stereotype of the absent father, explained Kenneth Rogers, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Greenville Health Systems in South Carolina. “Not all African-American fathers are absent—they are there,” he stressed. Rogers also emphasized that it is crucial for psychiatrists to extend an invitation to fathers—who are present in their children’s lives—to play an active role in the mental health treatment of their offspring.

Gogineni added that next year the AACAP committee that plans the annual meeting program expects to add other types of fatherhood to a similar session, including the role of a stepfather. “The United States is a diverse country, and we are accepting the diversity of fatherhood,” he said. ■