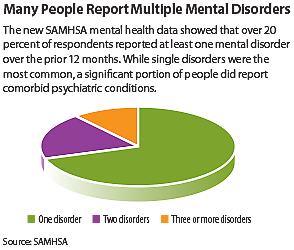

A newly released report from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) estimates that over 22 percent of American adults have one or more mental disorders that require some type of active treatment intervention.

While adults with one mental disorder account for most of this prevalence, the report also found that about 4 percent of adults have two disorders, while about 2 percent have three or more such disorders.

Among the specific disorders were adjustment disorder (present in 6.9 percent of the population) and major depressive disorder (6.0 percent)—these were the most common individual psychiatric disorders in the U.S. population, while substance abuse was the most prevalent category, occurring in about 7.8 percent of adults.

These new findings come from the Mental Health Surveillance Study (MHSS), a joint effort by SAMHSA and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). While SAMHSA provides periodic mental health data as part of its annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), this new report is the first to generate detailed nationwide data of representative adults using clinically based assessments.

As Sharon Larson, Ph.D., director of the Division of Evaluation, Analysis, and Quality and associate director for science at SAMHSA, told Psychiatric News, “The NSDUH format limits our data to broad categories like mental illness, serious mental illness, or depressive symptoms; this clinical analysis enabled us to take a deeper dive and examine specific mental conditions.”

In addition to providing overall prevalence rates for mental illness, the MHSS also describes the rates in relation to important correlates such as age, gender, income, and insurance status.

These analyses showed, for example, that women are much more likely than men to have one or more mood disorders or anxiety disorders, while men, particularly young men, are much more likely to have a substance use disorder.

It’s been about a decade since the last nationwide survey of specific mental disorders—the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) study, carried out from 2001 to 2003. However, the NCS-R was not administered by health professionals and used a survey methodology designed as a screening tool. The MHSS employed a modified version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID).

“SCID is the gold standard for diagnosing mental disorders,” said Michael Schoenbaum, Ph.D., of NIMH’s Office of Science Policy, Planning, and Evaluation. “This study used the same tool an individual patient would receive if they went to get diagnosed.”

Schoenbaum added that in light of time and resources available, the MHSS clinical assessments did not use a full SCID, and therefore some conditions, such as schizophrenia, could not be determined (though past-year psychotic episodes were quantified).

Even so, the assessments were one of the most comprehensive and rigorous ever conducted in such a large sample. The MHSS took place from 2008 to 2012 and involved 5,653 people who had participated in the NSDUH during the same span. In addition to having clinicians conduct the semistructured phone interviews, all results were reviewed by clinical supervisors.

New Data Come With Caveats

SAMHSA had initially planned to conduct about 3,500 clinical interviews among the NSDUH participants; the goal was to see how closely the clinical results matched the NSDUH data and then use the findings to develop a mathematical model to enable more-accurate scoring of future NSDUH efforts.

NIMH staff, who participated in the expert panels that initiated these assessments, decided to partner with SAMHSA and provided funding to include an additional 2,000 interviews, which would be enough to generate reasonably accurate stand-alone data. “Both of our organizations’ missions would benefit by having information available on the prevalence of specific disorders,” Schoenbaum told Psychiatric News.

“Carrying out structured clinical interviews can be difficult, as they are lengthy and require specially trained staff,” Larson added. “We are grateful we had the opportunity to partner with NIMH and make it happen.”

Both groups will use this new prevalence information to shape their future programs, whether in the areas of prevention, intervention, or priorities for future research. With the numerous correlates also factored in, the data should also help interested parties throughout the United States better understand the patterns of need—particularly unmet need—concerning specific disorders and populations.

One area of interest that the MHSS data cannot address, however, is identifying trends in mental health and mental illness. Though the new report included data from the NCS-R, the last large national survey, Michael First, M.D., a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, cautioned against the temptation of making apples-to-oranges comparisons, since the NCS-R data did not have the benefit of clinical judgments.

“The NCS-R data represent how an average person might classify people based on the symptoms they observe, while SCID data would be closer to a clinical truth,” said First, who assisted in training MHSS reviewers in using the SCID. “So you may see a lot of people in your office who look sad, but only a subset of them would actually have depression.”

If one keeps all the caveats in mind, though, there are interesting differences in the rates of some conditions under the two approaches; for example, the MHSS prevalence of social phobia (1 percent) and specific phobias (1.2 percent) was 6.1 and 7.5 percentage points lower, respectively, than found by the NCS-R. ■

The report “Past Year Disorders Among Adults in the United States: Results From the 2008-2012 Mental Health Surveillance Study” can be accessed

here.