Reflecting multiple ways of explaining the workings of mental illness, the National Academy of Medicine has awarded the 2015 Rhoda and Bernard Sarnat International Prize in Mental Health to Kay Redfield Jamison, Ph.D., and Kenneth Kendler, M.D.

Jamison, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, was honored for her research on affective disorders and suicide.

“However,” said the academy in a statement announcing the award, “her greatest impact may lie in her works of narrative nonfiction, which probe links between creativity and mental illness, trace the natural history of affective disorders, and explore the suicidal mind.”

Much of Jamison’s work for general audiences has gained resonance by drawing on her own experience with depression, suicidality, and bereavement.

“With our patients, so many are disenfranchised and voiceless and cannot advocate for themselves, so having someone like Kay Jamison is a necessary and precious advantage,” said Philip Wang, M.D., director of APA’s Division of Research, in an interview. “She provides an ideal blend of an academic’s perspective, a writer’s ability to communicate, and a patient’s actual experience to inform what she communicates. This gives her an incredibly powerful voice.”

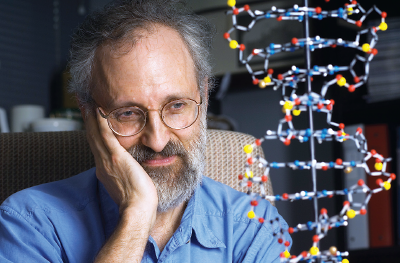

Kendler, a professor of psychiatry at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in Richmond, may be less well known to the public but he has written or co-written more than 900 scientific papers and has linked an inward view to genetics and an outward gaze at the environment and experience as his prime research domain. He also examines broader diagnostic, historic, and philosophical issues in psychiatry.

“Kendler represents the best of a humanistic tradition in psychiatry,” said Wang. “He really fathered a bottom-up approach that showed how genetic and cellular functions lead to complex behavior, thoughts, and feelings.”

Kendler’s expansive view of his field should come as no surprise for someone who was an honors double major in religious studies and biology as an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Two events propelled him into psychiatric research. During a psychiatry rotation in medical school at Stanford, he met his first patient with schizophrenia and wondered what could be going on in the mind to produce those symptoms. Later, a lecture on the opiate receptor stirred the excitement of how science could advance the understanding of psychiatric problems.

He has since worked largely at the ever-changing interface between statistical and molecular genetics on the one hand and psychiatric diseases—especially mood disorders, personality disorders, and psychoses—on the other.

“All the questions I think about are bridging the gap between clinical questions,” he said. He reads old psychiatry textbooks for enjoyment and patients’ charts for research. “I have an immense tolerance for sitting and reading psychiatric descriptions.”

His early career was spent studying neurochemistry, but he walked away from that in his early 30s, deciding that reductionist models were “way too simplistic.” He plunged into psychiatric genetics, tying them to the patient’s environment, stressful life events, childhood abuse, and more. The biopsychosocial model, he decided, was “soft, fuzzy, but basically right.”

In this, he has benefitted from massive scientific developments in molecular genetics, as research has progressed from relatively simple adoption studies in the late 1970s through gene-mapping, candidate gene studies, genomewide association studies, and now whole-genome sequencing.

Most recently, this has resulted in identifying and replicating two gene loci for depression among 12,000 people in China (

Psychiatric News, August 21).

Kendler is also a strong proponent within psychiatry of power calculations in research.

“He said if you’re serious about understanding something, you need adequately powered studies,” said Patrick Sullivan, M.D., a professor of genetics and psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an adjunct professor at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

“Very few people in the history of psychiatry have made such a massive set of contributions to the literature,” said Sullivan, who worked from 1996 to 2003 as an associate professor in the institute which Kendler directs at VCU. “He always wants to apply new methods to old problems to see if we can gain traction on them, and he’s been doing that for 30 years. Every paper of Ken’s that I’ve read has been exceptional in its care, thoughtfulness, and methodological rigor.”

Kendler’s longstanding interest in psychiatric nosology was boosted by an invitation from Robert Spitzer, M.D., to work on DSM-III-R in 1982. He was again involved in the development of DSM-IV and chaired the review committee that monitored scientific quality for changes in DSM-5. He also serves on the steering committee overseeing future revisions of DSM-5.

“Conceptual issues are important,” he said. “I wanted to increase the importance of empirical, evidence-based methods in psychiatric nosology and get away from the old model of just getting experts together and asking them to reach a consensus. I want to move psychiatry toward the approaches used by evidence-based medicine: looking at data and validators.”

The blend of scientific curiosity and alleviating the problems and suffering of people with mental illness has motivated him through his career.

“Science is quite strange, a self-disciplinary and evaluative process,” said Kendler. “We’re members of this aggregate enterprise, and we all contribute our little piece that in some way moves the science forward. What’s important about these awards is that in some way, the field is saying that what you do matters.” ■

Kay Redfield Jamison’s article on creativity and mental illness, “Great Wits and Madness: More Near Allied?” can be accessed

here. An abstract of “What Psychiatric Genetics Has Taught Us About the Nature of Psychiatric Illness and What Is Left to Learn” by Kenneth Kendler is available

here.