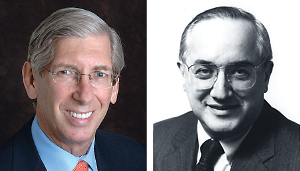

Louis Sokoloff, M.D., a giant in the history of psychiatric research, died on July 30 at the age of 93. He developed the first method to measure blood flow rates in every region of the brain and demonstrated that regional blood flow was associated with metabolic and functional neural activity.

In a 2003 interview Sokoloff said, “My most important research contributions were the development of the 2-deoxyglucose method and using it to show that local brain energy metabolism can not only be measured, but that it can be exploited to localize neural functional activity and even to image its distribution within the brain. In addition, we were able to use the method to define a number of the properties of the metabolic response to functional activation. For example, we showed that the changes in energy metabolism evoked by alterations in functional activity occur in the synaptic regions in the neuropil and not at all in the neuronal cell bodies. Furthermore, the change in the metabolic activity found in these regions in the neuropil reflects mainly the change in spike frequency in the terminals of the afferent pathways to the region.” The interview appeared in Recollections of the History of Neuropsychopharmacology Through Interviews Conducted by Thomas A. Ban, edited by P.R. Martin.

Lou was born and raised in South Philadelphia, the son of Jewish immigrants who had fled Ukraine. He attended the University of Pennsylvania and its medical school. After graduating in 1946, he entered military service, and after a brief training course, he served as a neuropsychiatrist. Like most psychiatrists at that time, he practiced psychotherapy. When one of his patients improved dramatically, he decided to spend the rest of his career trying to find out why. He believed that the secrets of the mind could be discovered only by studying the brain.

After discharge from the Army in 1949, Lou returned to Philadelphia and accepted a research assistant position with Seymour Kety, M.D. In 1953 he followed Kety to the newly established National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). There they developed the techniques to measure regional blood flow rates in the brain and eventually developed the groundbreaking method that became the foundation of functional brain imaging.

In 1969, following a sabbatical in Paris, Lou returned as head of the Laboratory for Cerebral Metabolism at NIMH. Using enzyme kinetics, he successfully developed the autoradiographic 2 [14C] deoxyglucose (a radioactive analogue to glucose) method to measure local cerebral glucose utilization. By 1971, he had pioneered in vivo use of this method in rats, leading the way for future adaptations in other animals and ultimately humans. His reports were published in the leading scientific journals including Science (1975), PNAS (1976), and Journal of Neurochemistry (1977). His adaptation of a glucose method for use in nuclear medical imaging with positron emission tomographic (PET) scanners was published in the Annals of Neurology (1979), renowned as a revolutionary method for detecting and treating brain disorders and still used today.

It was an exciting time in the field, and Lou was at the center of it at NIMH, where a revolution in psychiatric research was under way. Lou’s and Seymour’s commitment was not so much to psychiatry, or behavior, or even the brain, as to good science. They were instrumental in introducing a scientific orientation and methodologic rigor to the field of psychiatry and research on mental illness. In the process, they created a new discipline, and their students generated new academic departments around the country.

The mother church at Bethesda was quite special. Julius Axelrod, Ph.D., a future Nobel laureate, led a section parallel to Lou. Marshall Nirenberg, Ph.D., also a future Nobel laureate, was cracking the genetic code on the next floor. Seymour traveled around the world, receiving well-deserved honors, while Lou stayed at home, attending to his professional and personal families. His door was always open to discuss a scientific question or methodologic problem with anyone who sought his counsel.

In 1981, Lou received the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award, and along with Seymour, became the first recipient of the National Academy of Sciences Award in the Neurosciences in 1988. He was a visionary and pioneer in forging a scientific path for the field of psychiatry and developing the crucial methodology for studying the brain and how it related to human behavior at the dawn of neuroscience. Lou was one of the pivotal figures in the evolution of our field in the second half of the 20th century. ■