It has been more than two decades since researchers first proposed the accumulation of proteins called beta-amyloid (Aβ) to be a driving force behind the series of events in the brain that ultimately result in Alzheimer’s disease.

Efforts to reduce the levels of these proteins in the brain using antibodies have largely been a clinical disappointment—with most failing to reduce amyloid levels in the brain or demonstrate clinical benefit. However, the results of a phase 1b trial suggest the Aβ antibody aducanumab may help reduce Aβ in the brains of patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s—a change that was accompanied by a slowing of clinical decline.

The study, which was funded by Biogen, the manufacturer of aducanumab, was recently published in Nature.

This preliminary but promising success might be due to aducanumab’s ability to target Aβ fibrils, said study co-author Roger Nitsch, M.D., a professor of medicine at the University of Zurich. While the dense Aβ plaques are a visual hallmark of Alzheimer’s, smaller tangles of Aβ are also present in compromised cells and may represent the true toxic species.

As part of the trial, 165 patients with prodromal or mild Alzheimer’s disease were given monthly infusions of aducanumab (at one of four doses) or placebo over the course of a year in a test of the drug’s biological activity and tolerability.

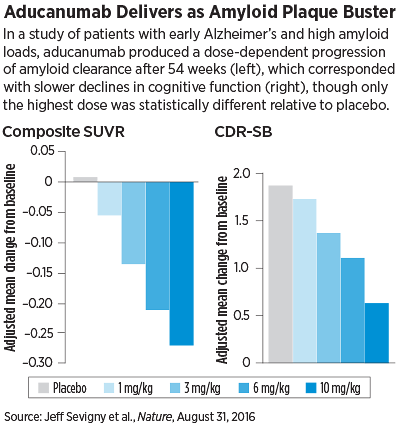

Not only did aducanumab perform well in these assessments—patients showed a steady dose- and time- dependent reduction in amyloid levels (measured by standardized uptake value ratios [SUVR] of positron emission tomography [PET] scans)—but it also appeared to slow cognitive decline after a year.

As with the amyloid clearance, participants taking aducanumab had lower progression in their Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores after one year. Patients taking the highest doses had on average the lowest score change since baseline.

While the cognitive findings attracted significant attention by Alzheimer’s researchers, Lon Schneider, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and gerontology at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California (USC) and director of USC’s Alzheimer’s Disease Center cautioned the results should be viewed with some healthy skepticism, since the study was not designed to address memory.

Schneider, who was not involved in this clinical trial, pointed out that the researchers carried out multiple neuropsychological assessments of the study participants, but only the CDR-SB and MMSE yielded an observable benefit for aducanumab—and even then the improvements were only statistically significant at the highest medication dose (10 mg/kg).

The fact that the large dose of aducanumab was required for the cognitive effect is an important observation, Schneider said, since the safety findings in the trial also revealed that this highest dose increased the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities—which reflect potential microhemorrhages and other vascular problems—in patients who carried the ApoE4 risk gene. Therefore, an important subgroup of patients might not be able to benefit from this drug, he noted.

“This antibody did exactly what it is engineered to do, in a very potent and predictable fashion, and given that some other amyloid-based drugs have failed this point, this is an important rite of passage,” said Schneider, who was a member of the working group that developed the APA Practice Guideline on Alzheimer’s and Other Dementias. “But when discussing what this trial showed, that’s where the period should end.”

Aducanumab Faces Hurdles Ahead

The next part of the story will be answered by a pair of large phase 3 studies of aducanumab that are already under way. These two international studies (which are identical except for the participating institutions) aim to enroll 2,700 people with early Alzheimer’s and compare aducanumab and placebo over 78 weeks, with CDR-SB now being the primary outcome measure. In consideration of the safety issues raised in this current study, ApoE4 carriers participating in the phase 3 will be capped at 6 mg/kg aducanumab.

Even if the trial finds aducanumab can improve cognition, there will still be patients who have dementia due to factors other than amyloid buildup and who may not benefit from the drug, including some who receive a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

Eric Reiman, M.D., executive director at Banner Alzhemier’s Institute Phoenix, noted that about a quarter of people who receive a clinical diagnosis of mild to moderate dementia, including more than a third of those without the ApoE4 risk gene, do not have biomarker or autopsy evidence of appreciable amyloid plaque deposition.

“If aducanumab is ultimately confirmed to have a clinical benefit and approved for use in patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, PET scans or other biomarkers would likely be needed to confirm the presence of amyloid plaques at which the anti-amyloid antibody is aimed,” said Reiman, who wrote an editorial regarding the recent Nature paper.

To date, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has been reluctant to pay for these expensive tests without additional evidence to support their value in the diagnosis or management of the disease. One large national study known as IDEAS is aiming to change this designation by assessing whether PET scans can influence clinicians’ decision making (

Psychiatric News, March 18).

“I personally believe that amyloid PET scans already have some value in the diagnosis and nonmedication management of certain patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia,” said Reiman. “But if anti-amyloid-like treatments like aducanumab are confirmed to have a clinical benefit, PET or other measurements of amyloid plaque deposits are likely to play major roles in the clinical diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Reiman is particularly interested in the implications for prevention, since amyloid plaques begin to accumulate more than two decades before the onset of dementia, and about 30 percent of healthy people over the age of 70 have appreciable plaques.

These anti-amyloid treatments may therefore have the most profound benefit if started before the disease is already extensive. If that proves to be the case, it would help to find amyloid screening tests that are less expensive than a PET scan and less invasive than a lumbar puncture to monitor response to the therapy in older adults, Reiman said.

Even as researchers continue to evaluate the effectiveness of anti-amyloid treatments, Reiman emphasized the importance of building a diversified portfolio of treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Combining anti-amyloid treatments with others that target other elements of the disease will likely prove even more effective than the individual treatments alone, particularly in the later stages of the disease, he suggested.

“For instance, imagine the chance to simultaneously target earlier stages and later stages of the disease in clinically affected patients, such that we could extinguish both the kindling and the fire in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease,” Reiman told Psychiatric News. “There is no guarantee that any of these treatment strategies will work, but now is the time to find out.” ■

“The Antibody Aducanumab Reduces Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease” can be accessed

here. Reiman’s editorial, “Alzheimer’s Disease: Attack on Amyloid-β Pro-tein” is available

here.