More than 15 years after the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center (WTC), thousands of men and women who helped with rescue, recovery, and cleanup at the site continue to experience physical and emotional scars, including a high prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Robert Pietrzak, Ph.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, and Adriana Feder, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, have been trying to better understand PTSD and other mental health trajectories in WTC responders. In their work, they have collaborated with other researchers at the WTC Health Program, a consortium of five centers established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in 2002 that provides treatment and medical monitoring for 9/11 responders.

Just as the WTC attacks were unprecedented in scope, so too was the response needed on the morning of the attacks and in their aftermath, bringing together police and paramedics with construction workers and asbestos handlers. The number and diversity of WTC responders, as well their willingness to share their experiences with researchers, has made it possible to uncover nuanced details about WTC-related PTSD trajectories, Pietrzak said.

“It’s not a simple matter of you have PTSD or you don’t,” Pietrzak said. “We’ve uncovered considerable heterogeneity in the severity of this disorder and how it evolves over time.”

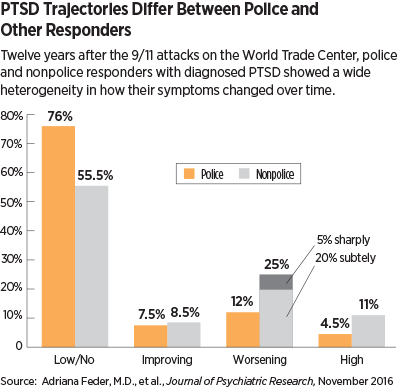

Pietrzak and Feder recently published a study in the Journal of Psychiatric Research that describes the heterogeneity of PTSD reported by professional and nontraditional responders 12 years after 9/11.

The study included 1,874 police and 2,613 other responders involved during and after the WTC attacks. As part of a health survey, the responders were given the PTSD Checklist Specific-Stressor (PCL-S) three, six, eight, and 12 years after 9/11. Participants also answered questions about various life stressors that took place in the year before and since 9/11.

For police responders, WTC-related PTSD symptoms grouped into four distinct trajectories, and for nonpolice responders, five distinct PTSD symptom trajectories emerged over time (see chart).

Many variables were consistent predictors of PTSD trajectories across both responder groups; for example, Hispanic ethnicity, psychiatric history prior to 9/11, greater exposure to the devastation caused by the WTC attacks, and maladaptive coping (such as substance use) strongly increased the risk of a symptomatic PTSD trajectory (everything but no/low symptoms). In contrast, higher perceived preparedness and a greater sense of purpose lowered the risk of symptomatic PTSD.

In another study, Pietrzak and his colleagues also identified a set of three typologies that comprise WTC-related PTSD. About 45 percent of responders with PTSD generally experienced all symptoms, while 31 percent had “dysphoric” PTSD that was characterized by emotional numbing and unease as the predominant symptoms, and 23 percent were part of a “threat” typology characterized by hypervigilance and avoidance.

“These predictors can help tell us how to prepare a diverse workforce to respond to a large-magnitude disaster,” Feder told Psychiatric News. “For example, rescue workers can be screened for their risk to identify people better suited for supportive instead of frontline roles that may experience more trauma.”

Feder, Pietrzak, and colleagues are also searching for biomarkers that may identify PTSD resilience. They have conducted more extensive interviews with over 300 responders from their cohort, who have also provided blood samples that will be used to measure stress hormone levels as well as the expression of stress-related genes.

Other groups have turned to WTC responders for clues about the effects of PTSD across the lifespan. For example, Sean Clouston, Ph.D., of Stony Brook University has been monitoring a subset of responders who live on Long Island to explore the role of PTSD in the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia.

“There is burgeoning interest in trauma and aging, suggesting some important connections between PTSD and dementia,” said Pietrzak, who’s been collaborating with Clouston on this endeavor. “Particularly, it involves the continual re-experiencing of past events that uses up a lot of cortical resources and may contribute to cognitive problems down the road for WTC responders.”

Another research team, led by Christina Hoven, Ph.D., M.P.H., of Columbia University is exploring the younger age spectrum and assessing the children of WTC responders to evaluate the generational effects of 9/11.

The real value of all this epidemiological data may be in how it can inform prevention and treatment for PTSD. Feder and Pietrzak noted that they just received a new grant to test a potential therapy. They will conduct a randomized trial of an Internet-based writing program that uses a novel, trauma-focused psychotherapy to help WTC responders find meaning in their trauma—testing whether sense of purpose can reduce PTSD symptoms.

“We are really excited to get the chance to apply some of our findings in therapy and see if we can improve some people’s lives,” Feder said. ■

An abstract of “Risk, Coping, and PTSD Symptom Trajectories in World Trade Center Responders” can be accessed

here. An abstract of “Latent Typologies of Posttrau-matic Stress Disorder in World Trade Center Responders” is available

here.