As the risk of concussion has risen higher in the consciousness of sports fans, players, and parents, so has the interest in finding better ways to diagnose and treat such injuries.

Now, a prospective study of more than 2,000 athletes published in the May 17 issue of the journal Neurology suggests that preinjury somatic symptom reporting may predict postconcussive symptom recovery.

For the study, Lindsay Nelson, Ph.D., an assistant professor of neurosurgery and neurology at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and colleagues recruited 2,055 physically and psychologically healthy high school and college athletes (80 percent male), who underwent a 90-minute preseason baseline examination. Out of this group, 127 sustained concussions involving a direct blow to the head. About 63 percent of the athletes with concussions played football and 24 percent soccer. The injured athletes received 60-minute postconcussion examinations four times: within 24 hours of injury and eight, 15, and 45 days later.

Most recovered fairly quickly, with 64 percent of the athletes recovering within one week and 95 percent within one month.

As has been previously reported in athletes who present with symptoms of concussions in outpatient specialty clinics, the authors found that symptom severity was the strongest predictor of longer recovery time.

In addition, higher baseline scores on the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 somatization subscale were independently associated with longer recovery from symptoms. Somatization appeared to increase either the athletes’ perception of their symptoms or their willingness to report them.

“The results don’t surprise me, but it’s important to firm up impressions with data,” sports psychiatrist Antonia Baum, M.D., a private practitioner in Chevy Chase, Md., and an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at George Washington University School of Medicine, told Psychiatric News. “Concussion symptoms are largely subjective, so it’s important to look at the patient’s background, not only for diagnosis but to guide treatment, as well,” added Baum, who was not involved with this study.

Neither depression nor anxiety was strongly associated with postinjury symptoms or recovery time.

“This finding rules out the possibility that acquiescence or general distress inflate symptom ratings broadly and instead points to a specific influence of somatization on postconcussive symptoms and subsequent recovery,” Nelson and colleagues wrote.

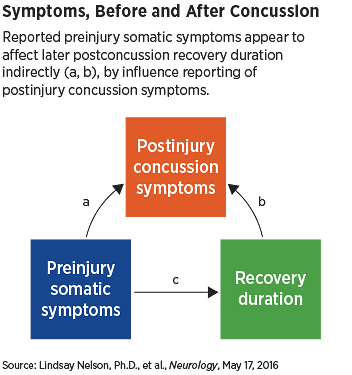

They further hypothesized that preinjury somatization affects the time for postconcussion recovery both directly and indirectly, by influencing the athletes’ reports of acute symptoms following injury. Ongoing subjective symptoms may lengthen impairment and increase service use.

“Of particular interest is that preinjury somatization’s role in predicting postinjury symptom recovery was related to its effect on postinjury symptom reporting rather than an effect of prolonging postconcussive symptoms,” wrote David Loring, Ph.D., a professor of neurology and pediatrics at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, and Michael Makdissi, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., of the Olympic Park Sports Medicine Centre in Melbourne, Australia, in an accompanying editorial. “These data also highlight that concussion assessment requires consideration of preinjury psychological function in addition to the postinjury clinical presentation.”

“[C]linicians should assess psychological health factors in the management of athletes recovering from sports-related concussions,” concluded Nelson and colleagues. “Future work clarifying the psychological, cognitive, and neurobiological underpinnings of somatization is needed to understand the mechanisms by which this construct contributes to enhanced experience or reporting of postconcussive symptoms and subsequent recovery time.” ■

An abstract of “Preinjury Somatization Symptoms Contribute to Clinical Recovery After Sport-Related Concussion” can be accessed

here. An excerpt of “Baseline Somatization Influences Sport-Related Concussion Recovery” is available

here.