Despite escalating tuition costs, medical students are willing to take on more and more loan debt, leading to a median indebtedness of $190,000 in 2016—compared with $32,000 in 1986 ($70,000 in 2017 dollars), according to a survey published in JAMA Internal Medicine on September 5.

The survey also revealed what the study authors called a “quieter” increase in the proportion of medical students graduating without debt, from 16.1 percent in 2010 to 26.9 percent in 2016.

“Although this [no-debt] finding seems positive, it suggests a concentration of medical students with wealthy backgrounds,” lead author Justin Grischkan, B.A., from the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry and colleagues wrote. In fact, an Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) report, published in Academic Psychiatry in April 2014, found the gap in socioeconomic backgrounds of medical students has widened: in 2005, more than 75 percent of the medical students enrolled came from the upper two quintiles of U.S. household incomes, and only 10 percent from the lower two quintiles. “The current trend in medical education costs will only further compromise efforts to increase the diversity of the physician workforce,” stated the report.

For the JAMA Internal Medicine report, researchers used de-identified data from the 2010-2016 AAMC Graduation Questionnaire to evaluate the trends in the distribution of medical education debt. They included 12,786 of 13,904 (92 percent) graduates who self-reported medical school debt in 2010 and 13,610 of 15,232 graduates (89.4 percent) who self-reported medical school debt in 2016. Figures were adjusted to 2016 dollars.

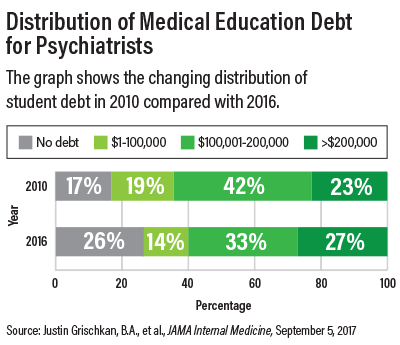

The researchers stratified medical education debt into one of four categories: no debt, $1 to $100,000, $100,001 to $200,000, and greater than $200,000.

Data indicated that among the students with debt, the mean amount increased from $161,739 in 2010 to $179,068 in 2016. Overall, 16.1 percent of graduates reported “no debt” in 2010 compared with 26.9 percent in 2016. The percentage of graduates reporting more than $300,000 in debt rose from 2.1 percent in 2010 to 4.2 percent in 2016.

“The mean scholarship funding increased from $53,065 to $58,136 between 2010 and 2016, but not substantially enough to justify the growth in medical graduates without debt,” the authors noted.

The researchers found that among graduates who pursued psychiatry, the percentage of those with “no debt” increased from 17 percent in 2010 to 26 percent in 2016; with $1-$100,000 decreased from 19 percent in 2010 to 14 percent in 2016; from $100,000-$200,000 decreased from 42 percent in 2010 to 33 percent in 2016; and more than $200,000 increased from 23 percent in 2010 to 27 percent in 2016.

The largest increase in “no debt” was among medical students in the following fields: radiology (from 17.1 percent in 2010 to 30.4 percent in 2016); dermatology (from 23.1 percent in 2010 to 36.1 percent in 2016); neurology (from 18.1 percent in 2010 to 30.7 percent in 2016); obstetrics and gynecology (from 11.5 percent in 2010 to 24.7 percent in 2016); ophthalmology (26.3 percent in 2010 to 39.9 percent in 2016); and pathology (from 20.8 percent in 2010 to 34.8 percent in 2016).

Another survey finding was that medical education debt is being carried by fewer individuals. This “disguises individual debt burdens behind aggregate debt estimates,” stated the researchers. The survey also found that the distribution of student debt across medical specialties has changed as well.

Higher tuition costs have important implications for medical students interested in certain specialties. “Medical schools must evaluate options for reducing the cost of medical education. The current rise in tuition is simply unsustainable, particularly for fields such as psychiatry and family medicine, where the debt-to-income ratio is becoming less favorable,” the AAMC report found.

However, there is a bright side: “psychiatrists’ expertise in communication, interviewing, physician-patient relationships, team-oriented approaches, and interprofessional education makes them uniquely suited to be at the table as academic medical centers begin to rethink their approach to education and revise their curricula. Their involvement from the beginning of the first year of medical school is critical for the development of mentoring and role-modeling relationships with medical students—particularly because role models have a significant influence on specialty choice,” the report stated.

The report also suggested that medical schools and psychiatry faculty inform students about opportunities to reduce their debt through programs such as the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) and the federal loan forgiveness program. The NHSC offers substantial tuition and loan repayment assistance for students who agree to serve in health professional shortage areas with the greatest needs.

Given the need for psychiatrists nationally, as well as the high number of psychiatry positions in federal, state, and nonprofit institutions, the AAMC report suggested that this debt-relief option may be attractive to students considering a career in psychiatry. ■

“Distribution of Medical Education Debt by Specialty, 2010-2016” can be accessed

here. “The Rising Cost of Medical Education and Its Significance for (Not Only) Psychiatry” is available

here.