Adding vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) to the treatment regimen of a patient with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) may lead to better long-term outcomes, according to a report published March 31 in AJP in Advance. The findings, based on the longest and largest naturalistic study of efficacy outcomes in TRD, suggest the superior outcomes of VNS may last up to five years.

VNS—a technique that delivers electrical impulses to the vagus nerve via an implanted device in the neck—has long been recognized as a possible adjunctive option for patients with TRD. APA’s practice guidelines recommend VNS as an add-on option for anyone who has not responded to at least four other approved depression therapies.

As a condition for approving VNS as an adjunctive treatment for TRD, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required a post-marketing surveillance study. In 2006, the Treatment-Resistant Depression Registry was established to track the clinical course and outcomes over five years of patients with TRD receiving adjunctive VNS and compare their health outcomes to TRD patients receiving usual care.

A total of 795 study participants were included in the study, 494 of whom received a VNS implant in addition to their usual treatments (which included medication, psychotherapy, and/or electroconvulsive therapy) and 301 of whom received usual treatment only. Both groups of patients had failed to respond to multiple therapies; at baseline, the mean number of failed treatments for depression was 8.2 in the VNS arm and 7.3 in the treatment-as-usual arm.

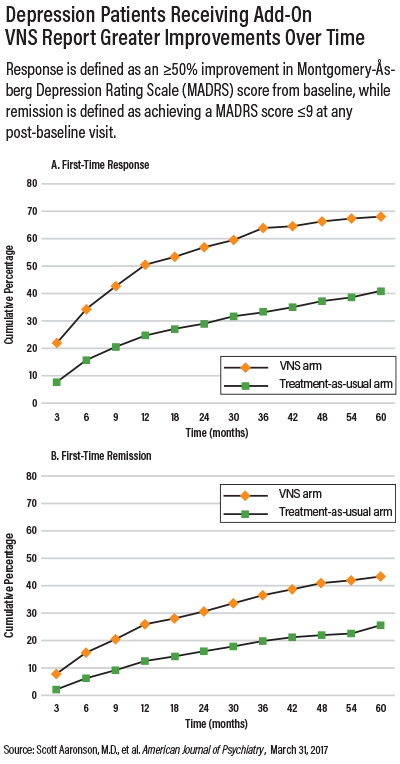

Follow-up visits, which included an assessment of changes in mood, occurred every three months for the first year and every six months for the remainder of the study. Response rate was defined as a 50 percent or greater reduction in a patient’s Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), and remission was defined as achieving a MADRS score of 9 or less.

Patients in the VNS group showed a five-year cumulative response rate of 67.6 percent, which was significantly higher than the 40.9 percent response rate in the usual-treatment group. VNS patients also had a higher remission rate of 43.3 percent compared with 25.7 percent in the usual care group.

Mark George, M.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) in Charleston, who was not involved with this study, told Psychiatric News that he is not surprised to see the long-term positive effects of VNS. George, who implanted the very first VNS device for depression in a patient in 1997, said he has been informally monitoring dozens of depression patients who have undergone this procedure at MUSC and said he had been “amazed by the long-term effects.”

“The patients by and large seem much more social and active than before,” George said. “When you get questions such as, ‘Is it okay if I scuba dive with my VNS implant?’ it suggests the patient is doing well.”

At the moment, however, VNS is not considered a standard treatment for TRD and thus is not generally reimbursed by Medicare or other health insurance plans. Scott Aaronson, M.D., director of clinical research at Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore and lead author of the study, told Psychiatric News that he hopes that these results will one day lead to changes in coverage for VNS for people with depression.

Aaronson noted that while the registry allowed for comprehensive analysis (patients included those with unipolar and bipolar depression, as well as comorbid anxiety disorder), treatment assignment in the registry was not blinded, which could have led to an increased expectation of therapeutic improvement.

“Before we can consider VNS as a routine part of depression management, we do need prospective data from a randomized, blinded, controlled trial with an improved design that incorporates what we have learned about the device from previous studies,” Aaronson said.

George said he hopes future studies might also point researchers toward biomarkers and screening tools that can help predict response to VNS. The procedure itself is minimally invasive and safe to use, but VNS does require surgery. Additionally, as the study showed, one in every three people will fail to respond to the therapy.

George suggested transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS)—a procedure that involves clipping electrodes to the ear (which contains terminals of the vagus nerve)—might offer a noninvasive option for determining patients most likely to respond to VNS,

Some pilot studies have shown that tVNS can reduce depressive symptoms, but George cautioned that non-invasive stimulation is still very much experimental (

Psychiatric News, September 2, 2016), and likely cannot produce a strong or sustained therapeutic effect. However, he noted that if tVNS proves reliable, then people who respond to the therapy might be considered good candidates for traditional VNS.

The Treatment-Resistant Depression Registry was sponsored by Cyberonics, Inc., which manufactures VNS devices. ■

“A 5-Year Observational Study of Patients With Treatment-Resistant Depression Treated With Vagus Nerve Stimulation or Treatment as Usual: Comparison of Response, Remission, and Suicidality” can be accessed

here.