A report by AMA’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs (CEJA) on physician-assisted suicide (PAS), or medical aid in dying, was not approved by the House of Delegates at its Interim Meeting last month and was referred back to CEJA by a narrow margin for further work.

The report asserted that the AMA’s existing code of medical ethics should not be amended and that it provides ethical guidance and support to those who oppose PAS as well as to those who support the practice in states where it is legal.

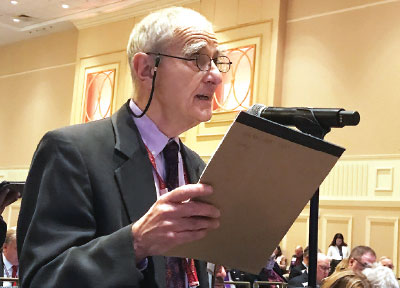

Psychiatrist Jim Sabin, M.D., who is chair of the council, testified during hearings on the report that AMA’s Principles of Medical Ethics, as currently written, “conveys balanced respect for the moral integrity of both sides.”

A foundational principle of the CEJA report was that physicians approach the subject of PAS with “irreducible differences” of opinion, such that both sides share a common commitment to “compassion and respect for human dignity and rights” (as stated in Principle I of the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics) but draw different moral conclusions from these shared commitments. (At last year’s Interim Meeting of the House of Delegates in Honolulu, CEJA sponsored an open forum on the subject of PAS where widely divergent views were expressed by physicians.)

In testimony during reference committee hearings on the report, Sabin noted that Section 5.7 of the code states that “physician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks.” Meanwhile, Section 1.1.7 (known as the conscience code) preserves the right of physicians to practice according to their conscience.

(The conscience code notes, in part, that “physicians are not defined solely by their profession. They are moral agents in their own right and, like their patients, are informed by and committed to diverse cultural, religious, and philosophical traditions and beliefs. … Preserving opportunity for physicians to act or to refrain from acting in accordance with the dictates of conscience in their professional practice is important for preserving the integrity of the medical profession as well as the integrity of the individual physician, on which patients and the public rely.”)

The CEJA report stated, “For some physicians, the sacredness of ministering to a terminally ill or dying patient and the duty not to abandon the patient preclude the possibility of supporting patients in hastening their death. For others, not to provide a prescription for lethal medication in response to a patient’s sincere request violates that same commitment and duty. Both groups of physicians base their view of ethical practice on the guidance of Principle I of the AMA Principles of Medical Ethics.”

In comments during reference committee hearings on the report, Sabin said the report was the result of debate that reflected “the best of the democratic process” on a highly contentious issue.

“We believe the code as it exists gives excellent moral guidance to our profession,” Sabin told delegates. “The existing opinion on PAS [5.7] expresses the value of opponents of PAS in an eloquent way, and the conscience opinion [1.1.7] expresses the ethical rationale for supporters in states where it is legal.

“This has been a long slog,” he continued. “The debate has been civil, thoughtful, and respectful on a topic that if not handled well could split the association.”

That the CEJA report was referred back to the council is hardly unusual; CEJA formulates AMA ethical principles around topics that are often among the most difficult issues in modern medicine, and it is not uncommon for reports to be referred back for numerous iterations before they are finally approved.

But PAS appears to be uncommonly fraught, with even the name for the practice being a subject for debate. (The CEJA report found “physician-assisted suicide” to be the most precise term and urged AMA to adopt the term.)

Opponents of the report argued that its conclusions were not supported by much of the text in the report and that the code as written could be used against physicians who participate in PAS in states where it is legal.

Psychiatrist Beth Morrison, M.D., said, “The code can be weaponized against physicians who practice aid in dying by stating that it is ‘fundamentally incompatible with a physician’s role as healer.’ ”

Supporters of the CEJA report disputed that claim, saying physicians practicing in states that have legalized PAS cannot be found unethical. Meanwhile, they argued that PAS was not a subject about which the AMA could afford to be neutral.

“Neutrality is not neutral,” said Daniel Sulmasy, M.D., Ph.D., senior research scholar at Georgetown University’s Kennedy Institute of Ethics, who argued in favor of approving the report.

He said that if the AMA were to declare itself neutral on the issue, “the flood gates would open” and PAS would quickly become legal in more than the six states and the District of Columbia where it is already permitted. He said the CEJA report “stands for integrity.” ■