The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February approved the marketing of the first blood test to aid in the evaluation of traumatic brain injury (TBI). The test, called the Brain Trauma Indicator, measures the levels of the proteins ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), which are both released from the brain into the blood in the immediate aftermath of a head injury. The plasma concentrations of these proteins can indicate whether a patient who has experienced a head injury has intracranial lesions—or brain bleeds.

Currently, the presence of intracranial lesions can be detected only by using computed tomography (CT) scans, which, while effective, are expensive and expose a patient to radiation. The Brain Trauma Indicator, marketed by Banyan Biomarkers, can predict the presence or absence of such lesions with nearly 99 percent accuracy if administered within the first 12 hours following an injury (test results take around 3 to 4 hours). This accuracy rating is based on a clinical study in which blood samples from 1,947 adults with suspected mild TBI (mTBI) were tested and the results were compared with CT scans.

“A blood-testing option for the evaluation of mTBI/concussion not only provides health care professionals with a new tool, but also sets the stage for a more modernized standard of care for testing of suspected cases,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., said in a press release. “In addition, availability of a blood test for mTBI/concussion will likely reduce the CT scans performed on patients with concussion each year, potentially saving our health care system the cost of often unnecessary neuroimaging tests.”

While this TBI-related blood test is an important clinical breakthrough, some neurological experts have been sounding notes of caution about the limitations of the test.

“There are scenarios where this blood test can be very useful, but I believe these occurrences will be the exceptions rather than the norm,” said John Leddy, M.D., director of the concussion management clinic at the University at Buffalo.

Leddy told Psychiatric News that there are multiple, validated clinical algorithms—such as the New Orleans Rules or the Canadian CT Head Rules—that doctors can use to assess a TBI patient and guide decision making about whether the patient needs a CT scan or not. According to Leddy, these algorithms usually provide a clear answer. “Even in a situation where the results are not definitive, can you afford to wait four hours for the blood test to come back with a patient who might have internal bleeding?” he asked.

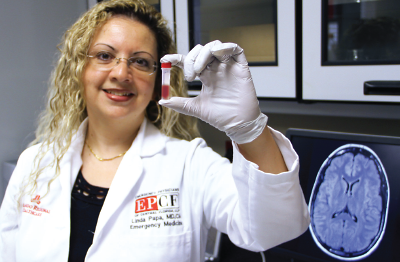

Linda Papa, M.D., an emergency medicine physician at the Orlando Regional Medical Center who has led many of the research studies with UCH-L1 and GFAP, acknowledged that the current test does have its limitations.

“This blood test won’t be efficient in emergency settings until we can develop a point-of-care version that provides results within an hour,” Papa told Psychiatric News. “However, it is worthwhile to have a new option to guide care for the many instances of less-severe head injury where patients are already placed under observation for several hours.”

Children and adolescents with TBI could especially stand to benefit, since research has shown that children are more sensitive to potential CT radiation damage. Papa noted that the current version of the test is only for adults, but that clinicians could use a test off-label if circumstances are appropriate. She and her colleagues have conducted multiple studies with children that suggest these two proteins are equally valid biomarkers in pediatric TBI.

In the future, Papa said she believes that in the future the blood test might be useful for predicting a TBI patient’s long-term prognosis. Papa has recently completed a clinical study that monitored patients for six months following their TBI to see if UCH-L1 and GFAP levels correlate with long-term outcomes, and she is currently analyzing the data.

If there are associations between the plasma levels of these proteins and long-term outcomes, clinicians could use these blood tests to assess patients and plan more aggressive rehabilitation strategies in cases where the results suggest a risk of cognitive deficits or other problems. ■