Systems matter.

That’s a crucial lesson that APA’s presidential Work Group on Psychiatrist Well-Being and Burnout has learned about what accounts for health and wellness—or for burnout—among America’s physicians: the broader system and contextual framework in which a physician is working may be the most significant factor shaping that physician’s reactions to stress.

As has been reported in Psychiatric News, the work group has met throughout this past year. We split into subcommittees to handle different components of the review and recommendations. We reviewed literature on a range of subjects and looked at other interventions and informational guidelines.

The products and ideas coming out of the committee’s work have led to the creation of an online resource for psychiatrists (and other health professionals) to provide screening information on relative risks of burnout and depression, as well as support for addressing some forms of stress and distress. We reviewed and selected two screening instruments (Oldenburg and PHQ-9) to help members identify their relative risk of burnout or depression. The tools can be found on APA’s website at psychiatry.org/burnout. A number of psychiatrists have accessed the online module for the screening and informational components. On the basis of our preliminary analysis of the results, we are concerned about the degree of burnout and mood symptoms of psychiatrists.

The work group has also created the

Ambassadors Toolkit. The toolkit includes a PowerPoint slide deck and companion manual to help you advocate for systemic reform in your home institution or organization. The slide deck can be modified to match the needs of your organization as you spread awareness of physician burnout and assist your organization in addressing the wellness and burnout needs within your work community.

In the process of reviewing and implementing support for APA members, we have attempted to understand the personal and clinical experiences of individuals with various forms of toxic stress associated with the health profession. At the same time, we have recognized the importance of taking a broader, more systems-based perspective of the problems and how they emerge within, are affected by, and affect other parts of the system.

At a symposium on physician well-being in 2015 by the Accreditation Commission on Graduate Medical Education, Dewitt Baldwin, M.D., presented a comprehensive “

concept map,” which depicts progressively broader areas of focus, all of which influence physician well-being. These start with the individual and extend outward through the program, institution/organization, specialty, profession, and the health care system. Encompassing all of these is the wider political environment, and policy decisions at the local, state, and national levels.

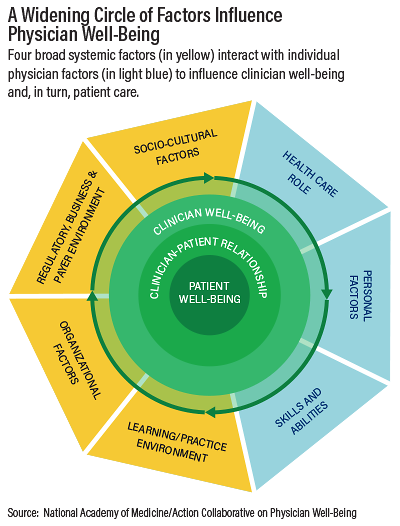

In addition, several APA leaders have been participating in the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being. The collaborative has derived a slightly simpler scheme (see chart) illustrating four broad systemic factors affecting physician well-being and resilience:

•

Learning/practice environment: This comprises such issues as autonomy, collaborative versus competitive environment, mentorship, professional relationships, team structures and functionality, and workplace safety and violence.

•

Regulatory, business, and payer variables: These include, among others, documentation and reporting requirements, compensation issues, maintenance of licensure and certification, reimbursement structure, and shifting administrative rules.

•

Sociocultural factors: These may include the workplace culture of safety and transparency, discrimination and overt and unconscious bias, media portrayal, patient behaviors and expectations, political and economic climates, and stigmatization of mental illness.

•

Organizational factors: These comprise the organization’s mission and values; culture, leadership, and staff engagement; data collection requirements; diversity and inclusion; level of support for all health care team members; professional development opportunities; scope of practice; and workload, performance, compensation, and value attributed to work elements.

These broad systemic factors interact with one’s genetic, cultural, and personality factors—designated in the map as “health care role,” “personal factors,” and “skills and ability”—to create those experiences that contribute to toxic stress and ultimately impact patient care.

A concept map like Dr. Baldwin’s helps to graphically articulate a systems-based view that can stimulate relevant policy discussion, process improvement, and research. Now is a time when such an approach is needed.

A public health systems perspective on physician burnout helps to identify upstream or antecedent events/factors that contribute to the prevalence and severity of burnout so that effective interventions can be developed and implemented at all levels—individual, team, organization, and health care system.

Don Berwick, M.D., former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and president of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, has somewhat famously said, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets”—meaning that, whether intended or not, the design of a system (including alignment of incentives) will dictate and reinforce the outcomes that are observed.

The same holds true for understanding physician health and wellness: we have a system perfectly designed, in some ways, to produce burnout. Developing individual interventions is useful and necessary, but we cannot ignore or abandon the potential for larger-scale improvements by taking a public health and systems perspective. ■

APA’s burnout and wellness toolkit can be accessed

here. The 2015 ACGME symposium on physician wellness, including a conceptual map of systemic factors, is available

here. Information about the National Academy of Medicine Action Collaborative on Physician Resilience and Well-Being is located

here.