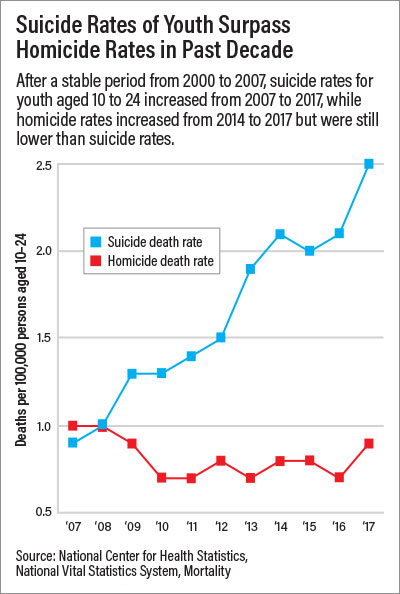

The rate of suicide among youth aged 10 to 24 has climbed steadily over the past decade, increasing 56% from 2007 to 2017, surpassing the homicide death rate for this age group, according to a report issued last month by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Deaths due to suicide and homicide, referred to as violent deaths by the CDC, have consistently been a major cause of premature death for individuals aged 10 to 24 in the United States. In 2017, suicide was a second leading cause of youth death, claiming the lives of nearly 6,700 individuals aged 10 to 24, while homicide ranked as the third leading cause of death for individuals aged 15 to 24 (and fifth leading cause of death for youth aged 10 to 24). In fact, the death rate for suicide exceeded that of homicide in youth for the first time in 2010, and it has done so every year since.

Youth Suicide Research Urgently Needed

“The truth of the matter is we don’t know what is causing this alarming rise in youth suicide rates,” said Maria A. Oquendo, M.D., Ph.D., past APA president and professor and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. Oquendo is also a director on the National Board of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

“What is most disturbing to see is that the largest rate of increase in suicide deaths was in younger children, aged 10 to 14,” Oquendo said. “The mean onset of mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders is around age 15, so you don’t expect to have children of that age dying by suicide.”

Although the youth suicide rate was lowest among 10- to 14-year-olds in 2017 (2.5 deaths per 100,000), this group experienced the largest increase—with a suicide death rate nearly three times higher than in the prior decade (177%). Among 15- to 18-year-olds, the suicide rate rose 76%, and 36% for 20- to 24-year-olds. One possible explanation for the uptick in suicide among children may be that menarche and the onset of puberty is happening earlier, Oquendo said. Some studies have associated early menarche with higher rates of both depressive symptoms and antisocial behaviors. Psychological autopsies, which rely on extensive interviews with friends and family of the deceased to study suicide, have found that 95% of individuals who die by suicide had a mental illness, typically a mood disorder, she explained.

“More research is needed on what is driving the rise in youth suicides,” said Eraka Bath, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and director of the Child Forensic Services Program at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Recent studies suggest the importance of examining the impacts of social media exposure on cyberbullying as well as on the development of anxiety and depressive disorders. Additionally, we need improved understanding of how excessive screen time may affect empathy and reward circuits in the brain.”

Oquendo said that youth exposure to vaping is another major concern. “We know that youth exposure to nicotine is associated with increased risk for suicide, as is use of other substances, such as drugs and alcohol.”

Data Point to At-Risk Youth

Although the CDC report did not discuss race or ethnicity, a recent study in Pediatrics suggests that suicide attempts by black adolescents may be rising. The findings were based on data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS)—a national survey administered to high schoolers across the United States—from 1991 through 2017. As part of this survey, youth were asked to report suicidal thoughts and behaviors.

While the analysis revealed that the rates of suicidal ideation and suicide plans by the adolescents trended downward over time across sexes and racial and ethnic groups, black adolescents experienced an increase in rates of suicide attempts, the authors reported. This trend was not seen in adolescents who identified as white, Hispanic, Asian American, Pacific Islander, or multiracial.

“These racial and ethnic nuances are important and need to trickle up to psychiatrists’ awareness for improved training, better screening and assessment, and more robust prevention and intervention,” Bath said. “Given that minority populations are particularly impacted by structural factors, such as racism and discrimination, lack of access to mental health care, poverty, and community violence, we need to think about elements of risk beyond what we traditionally learn about in our training, which prioritizes symptoms and specific disorders and overlooks these factors.” She called for more research on racial and ethnic differences in youth suicide.

Another group of youth who may be at a higher risk of suicide are those whose parents are in treatment for psychiatric disorders and have a history of suicide attempt, Oquendo added.

“We should be treating these children the same way that we treat children of cancer patients: We need to alert these patients to the familial aspect of this illness and the importance of monitoring their children. But because of the stigma of suicide, the parents’ history of suicide attempt is often hidden, and these opportunities for intervention are lost.”

Screening Can Save Lives

“We are on the front lines of having an opportunity to intervene and hopefully stop this trajectory,” said Gabrielle Shapiro, M.D., chair of APA’s Council on Children, Adolescents, and Their Families and a clinical professor of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. With even the youngest patients at risk for suicide, screening and assessment for suicidality and depression should be frequent and routine, she said.

Another effective means of lowering youth suicide rates would be educating teachers and parents on how to recognize troubling behavior at home and in school, she said. The APA Foundation’s Typical or Troubled school mental health education program has been successfully implemented in dozens of cities in the United States to do this.

Oquendo said treatment does make a difference in preventing youth suicides. Particularly effective are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as well as suicide-specific therapies such as cognitive therapy for suicide prevention and dialectical behavior therapy. Also proven effective is the use of safety planning interventions, which allow the patient to make a concrete plan for weathering a potential suicidal crisis. Safety planning can be provided in any setting, including schools or emergency rooms, and various professionals including teachers and mental health professionals can easily be trained to help patients complete these lifesaving plans, she said. ■

“Death Rates Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017” is posted

here. “Trends of Suicidal Behaviors Among High School Students in the United States: 1991–2017” is posted

here. For a patient safety plan template, visit

here.