“I have lately obtained the exclusive care of the maniacal patients in our hospital,” wrote Benjamin Rush to a friend in the autumn of 1787. The appointment was a longstanding dream for Rush, who had already spent 18 years as a physician in Philadelphia, and later earned him a place as the father of American psychiatry.

“Rush’s most important contribution to the development of psychiatry was his attempt to destigmatize people with ‘insanity’ by assuming that their treatment could be hospital based, just as with patients with other illnesses,” said Jeffrey Geller, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, in Worcester.

Rush was certainly not the only American of his day concerned with the care of people with mental illness. Over several generations, the Galt family of Virginia managed the Williamsburg asylum, which opened in 1773, for example.

Rush’s interests went far beyond mental illness, and he wrote compulsively about them all. He produced a torrent of pamphlets, essays, letters, books, and articles and published lectures on general medicine, infectious disease, military medicine, politics, philosophy, criminology, mental health, education, and slavery.

Rush’s path to becoming a leading figure in early American medicine and a signer of the Declaration of Independence began modestly. He was born in Byberry, Pa., just north of Philadelphia, on Christmas Eve in 1745, the fourth child of a blacksmith. The family moved to Philadelphia in 1751, but his father died soon after. Fortunately, young Benjamin was a good student. He graduated at age 13 from boarding school and entered the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) as a junior, graduating just three months shy of his 15th birthday.

While Rush had initially planned to become a lawyer, his interest switched to medicine. From 1761 to 1766, he apprenticed with Dr. John Redman, a prominent physician in Philadelphia. (The first medical school in the 13 colonies wasn’t founded until 1765 at what became the University of Pennsylvania.) Besides following the doctor on his rounds, young Rush also read deeply on medicine and bought tickets to anatomy lectures by Dr. William Shippen Jr., who had just returned from formal medical study at schools in London and Scotland. The classes included occasional dissections of the bodies of criminals or people who had died by suicide.

To learn more, Rush sailed to Edinburgh in 1766 to study at that city’s renowned medical school, graduating in 1769. He returned to become the colonies’ first professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia. (Benjamin Franklin was the first president of the school’s board of trustees.)

Less than three weeks later, he was called out on his first psychiatry case, a Capt. John Macpherson, who exhibited symptoms of what today would be called mania and paranoia. He also cared for Macpherson’s distraught wife, thus learning a lesson about the need to care for the families of patients.

Rush argued for consideration of the whole person. “Knowledge of the mind opens to [the physician] many new duties,” Rush wrote. “It is calculated to teach him that in feeling the pulse, inspecting the eyes and tongue, examining the state of the excretions, … he performs but half his duty in the sick room.”

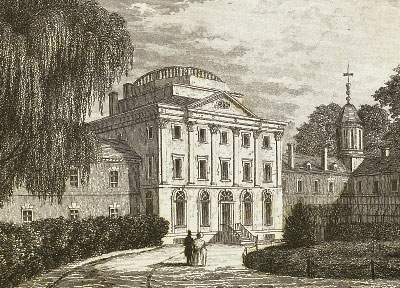

Rush joined the staff of Pennsylvania Hospital in 1783. Besides the general medical patients, the hospital housed 30 people with severe mental illness in dank basement cells about 10 feet square. In 1787, he was formally given charge of the care of these patients. He installed stoves in the cells to keep the patients more comfortable and allowed them to take walks outside their cells and be treated by the doctors.

More broadly, Rush sought “a common underlying pathologic process” expressed as a “unitary theory of disease,” as one historian of medicine has written.

From Hippocrates on, medicine had cycled through a number of presumed biological options for the origins of mental illness, a source that might be the liver, the spleen, or the intestines. Rush’s medical training in Edinburgh acquainted him with the latest theory, a “vibration of the nerves.” Later, Rush came to believe that the flow of blood in the body was the source of all illness, mental or physical.

“I infer madness to be primarily seated in the blood-vessels, from the remedies which most speedily and certainly cure it, being exactly the same as those which cure fever or disease in the blood-vessels from other causes, and in other parts of the body,” he wrote. As a result, his prescription for psychiatric illness differed little from that for any other: bloodletting, emetics, wine, exercise, alternating warm and cold baths.

After seven years of urging, Rush finally won approval in 1794 for a new wing of the Pennsylvania Hospital to house patients with mental disorders. It was a watershed moment. That same year, Phillippe Pinel in Paris began publishing about traitement moral, the more humane, psychological approach to caring for people with mental illness and one that would have more influence over the next century than Rush’s.

In his compendium on mental illness, Medical Inquiries and Observations Upon Diseases of the Mind, published a year before his death in 1813, Rush set forth his own diagnostic toolkit. “Amenomania” was a form of psychosis, characterized by delusions and hallucinations, he wrote. The patient “denies he has any disease,” may believe that he is “the peculiar favourite of heaven,” and is “now happy in the errors which accompany his madness.”

“Mania” was accompanied by “high or low spirits,” “great rapidity of thought,” “irritability of temper,” “instability in all pursuits,” and “unusual acts of extravagance,” among other symptoms.

“Manalgia” had symptoms that sound like depression: “taciturnity, downcast looks, a total neglect of dress and person, long nails and beard, dishevelled or matted hair, indifference to all surrounding objects, insensibility to heat and cold.”

Approaching a patient afflicted with madness, he advised, the physician’s gaze should be “mild and steady,” accompanied by a “harsh, gentle, or plaintive” voice (depending on circumstances) and “dignified” conduct. “A physician should treat his deranged patients with respect. … Acts of justice and a strict regard to truth tend to secure the respect and obedience of deranged patients to their physician.”

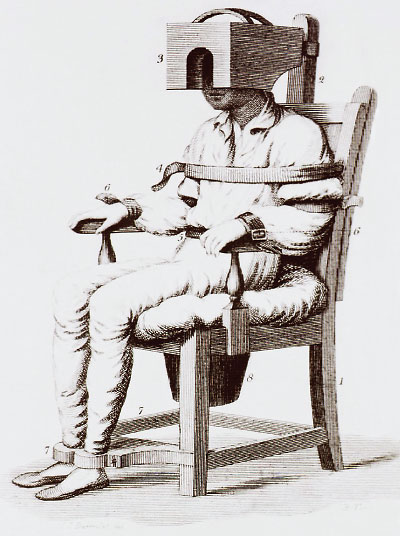

If that didn’t work, Rush suggested using straitjackets, strapping the patient in a special chair, “privation of customary pleasant food,” “pouring cold water under the coat sleeves,” or a 20-minute shower.

“If all these modes of punishment should fail of their intended effects, it will be proper to resort to the fear of death,” he continued, covering every possibility.

And, of course, active treatments usually included some combination of bleeding; purging the bowels; induced vomiting; blistering the skin; cold (air, water, or ice); and administration of mercury, antimony, quinine, opium, digitalis, and more.

Strange as they sound today, we should be careful of dismissing Rush’s views on illness and cures, said Geller.

“Bleeding, purgation, and so on were simply the best practices of the day, and he believed them to be effective,” he said. “In 75 years, maybe people will be aghast at how we treat psychiatric patients in 2019. Rush used what was available and sometimes got results.” ■