Opioid-related deaths in the United States jumped 18.5 percent between 2014 and 2016, with illicit synthetic opioids—mainly street fentanyl and fentanyl derivatives—extracting a particularly lethal toll in the Northeast and Ohio River Valley, according to a study published in JAMA Network Open.

Mathew V. Kiang, Sc.D., a postdoctoral research fellow at Stanford University School of Medicine, and colleagues analyzed data from the National Center for Health Statistics on more than 350,000 Americans who died from opioid-related causes from January 1, 1999, through December 31, 2016. They compared the mortality rate per 100,000 people among the states and the District of Columbia from all opioids, heroin, synthetic opioids, and natural opioids such as morphine. The natural opioids group also included semisynthetic opioids such as prescription hydrocodone and oxycodone.

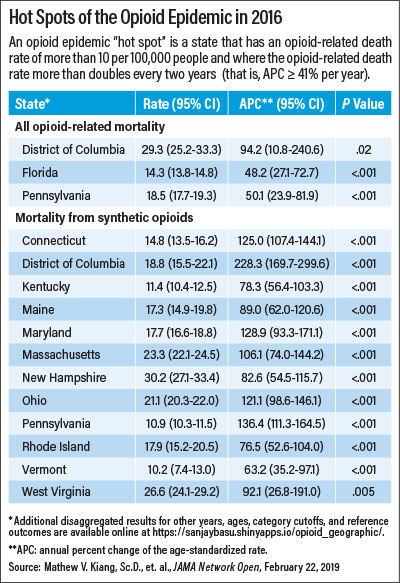

The researchers found that 27 Eastern states and the District of Columbia had synthetic opioid-related mortality rates that at least doubled every two years. In 14 of those places, synthetic opioid deaths doubled every year. The District of Columbia was hardest hit, with deaths from synthetic opioids more than tripling every year. Twelve of the 28 states had mortality rates from synthetic opioids of more than 10 per 100,000 people (see table).

In several states, deaths from synthetic opioids outpaced deaths from heroin, a finding that surprised Kiang.

“Previously, illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids were distributed through adulterated heroin. The fact that some states have higher synthetic opioid mortality than heroin mortality suggests this is not necessarily the case anymore, and synthetic opioids have worked their way into other illicit drugs,” Kiang told Psychiatric News. “This may be an early warning to other states that just because they have not had a surge in heroin mortality, that doesn’t mean they will be immune to future synthetic opioid mortality.”

Kiang posited that the regional increase in synthetic opioid deaths may be an offshoot of long-term regional differences in heroin.

“Some types of heroin are much easier to adulterate with fentanyl. These types have largely been concentrated in the eastern half of the United States,” Kiang said. “The geographical spreading of mortality likely reflects the geographical spreading of these illicit drug markets that [already] have increasingly more potent heroin.”

Robert Feder, M.D., a psychiatrist in Manchester, N.H. and a member of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry, noted that the concentration of synthetic opioid deaths in the Northeast and Ohio River Valley may be a remnant of old prescribing patterns.

“In New England, you have the greatest number of doctors per square miles, so there were a lot of doctors there prescribing a lot of opioids. In the Ohio River Valley, they don’t have quite the concentration of doctors, but a huge number of pill-mills sprung up there,” said Feder, who was not involved in the research. “As the opioid crisis became apparent, prescribing was significantly reduced and as a result, [those with substance use disorders] who were using oxycodone and the like went to heroin. Then suppliers realized it was easier and cheaper to make fentanyl.”

Kiang said that the most important intervention in the nation’s opioid crisis is treatment.

“Psychiatrists and all medical professionals are the frontline workers in this intervention. We need to provide treatment that is accessible and affordable to anybody who needs it. It should not be easier to get heroin than to get help,” Kiang said. “Ultimately, like most public health problems, the opioid epidemic as a whole is going to require a multipronged attack that involves addressing both the immediate problem of fatal overdoses as well as the upstream factors and socioeconomic conditions of opioid use. Addressing the mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, that drive opioid use is incredibly important and too underrecognized.”

Feder encourages psychiatrists—including generalists and others who do not specialize in addiction psychiatry—to become certified to prescribe buprenorphine.

“Buprenorphine treatment has been very successful, but there aren’t enough physicians doing it, especially psychiatrists. The only psychiatrists who seem to be doing a significant amount of buprenorphine treatment are those who specialize in addiction psychiatry,” said Feder. “Most physicians who are prescribing buprenorphine are nonpsychiatrist primary care doctors, who are not able to treat the comorbid psychiatric conditions that often go along with opioid use disorder. We need more psychiatrists getting involved to treat these patients.”

This study was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health. ■

“Assessment of Changes in the Geographical Distribution of Opioid-Related Mortality Across the United States by Type, 1999-2016” can be accessed

here.