Medications have long been used to treat mental illness. Laxatives, sedatives, opiates, barbiturates, insulin, and other compounds were tried by physicians who were desperate to help people with mental illness, achieving occasional transient relief of symptoms but no lasting effects.

Effective drugs became available starting only in the mid-20th century, but their discovery largely depended on a serendipitous choice of compound coupled with astute observation. What was missing was knowledge of the underlying brain functions that caused mental illness and could serve as the basis of drug development, knowledge that may be revealing itself only now.

Four examples might be said to have kicked off the modern era of psychopharmacology.

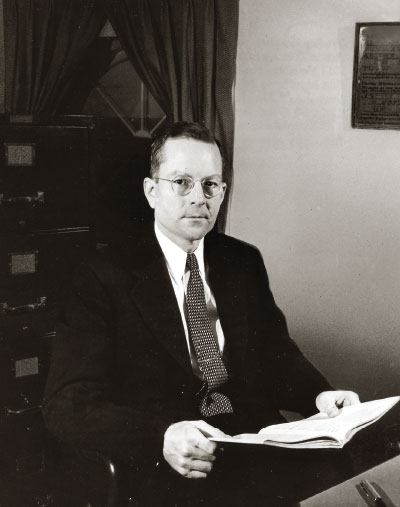

In 1937, Charles Bradley, M.D., a child psychiatrist in Providence, R.I., gave Benzedrine to children diagnosed with behavioral disorders for headaches. The stimulant drug didn’t help the headaches, but some children paradoxically became less aggressive or noisy and did much better in school. Bradley published his results in the November 1937 American Journal of Psychiatry, but it drew little attention for two decades until 1956, when methylphenidate came on the market as a treatment for what is today called attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In 1949, the Australian psychiatrist John Cade, M.D., in search of a treatment for mania, injected guinea pigs (“on a whim,” said historian Edward Shorter) with lithium. The animals grew uncharacteristically docile. He then gave the drug to 19 patients, including 10 with mania, all of whom improved remarkably. Even so, it wasn’t until 1970 before the FDA approved lithium, now a mainstay for mania.

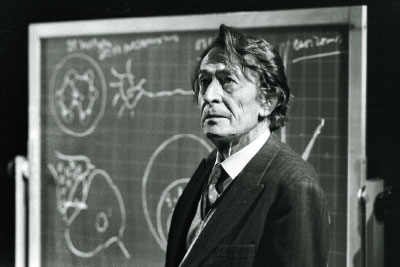

Again in 1949, French surgeon Henri Laborit, M.D., began experimenting with a phenothiazine antihistamine in hopes of improving the effects of anesthesia. By the mid-1950s, French and American psychiatrists showed that a newly synthesized phenothiazine—chlorpromazine—could lessen agitation, delusions, and hallucinations in patients with psychosis.

People with tuberculosis who were treated with isoniazid and iproniazid seemed to have improved mood, which led to the development of imipramine for depression by Swiss psychiatrist Roland Kuhn, M.D.

These drugs were all treated as major breakthroughs in their time. Some remain in use today; others led to the development of variants with presumed improved therapeutic effects or fewer side effects. Yet all originated in compounds originally developed for other purposes. None was the result of an understanding of the brain’s workings.

“Biology was not sophisticated enough in those days to figure out a rational pathophysiologically based drug discovery platform,” said Charles Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D., a prominent researcher. He is chair and a professor of psychiatry and director of the Institute for Early Life Adversity Research in the Department of Psychiatry at the Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin.

In addition, advances inevitably would come more slowly after the early breakthroughs in each diagnostic category.

“If you have a 50% response when you’ve started from zero, it’s considered impressive,” said former APA President Alan Schatzberg, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University and a psychopharmacology researcher. “After that, the cost of incremental gains became greater.”

Yet another issue, said Schatzberg, were changes in criteria over the decades. For instance, when imipramine appeared, it was used in the most severely ill patients, many of whom responded well. But as criteria widened from DSM-III to DSM-IV to DSM-5, “depression” came to encompass cases with milder symptoms.

“Depression is now more heterogenous in its definition, symptoms, and responses,” he said. “The less severe cases are less likely to separate from placebo because of that widened definition.”

Chance—or serendipity helped along by some astute pharmaceutical chemists at many drug companies—may have played a large role in the development of those early drugs, but chance favors the prepared mind, as Pasteur said. Bradley, Cade, Laborit, Kuhn, and others were curious and ready to take chances when the time came.

Creating more focused medications with fewer side effects might be aided by increased understanding of the brain and its component mechanisms. Identifying receptors or circuits involved in the development of mental illness might lead to the development of more targeted drugs. Yet that ideal has been delayed by the immense difficulties inherent in neuroscience research.

“Given that the brain is more complicated than the heart or the liver, it’s no surprise that disorders that are the most human have been the hardest to address,” said Nemeroff.

However, the long and slow search of the brain is beginning to bear fruit, according to Joshua Gordon, M.D., Ph.D., director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

“It is too early to tell if the field has reached an inflection point, but NIMH and the National Institutes of Health have invested in neuroscience research for decades,” said Gordon in an interview. “That has laid a foundation for understanding how the brain works, which can be exploited for developing novel treatments.”

He cited the approval of brexanolone as an example of the possibilities. Decades of basic research into the biology of neurosteroids combined with observations on how hormones were altered in the postpartum period led to development of what Gordon called “the first true neuroscience-driven drug in psychiatry.”

Perhaps better known is the investigation of ketamine and its derivatives.

“Ketamine was tried because of the possibility that glutamate might be involved in depression, so it merited a hypothesis,” said Gordon. “We were a little bit lucky that it worked.”

Ketamine also showed that the brain is capable of responding rapidly. Follow-up compounds may retain that advantage without the side effects of the original drug. Yet there is still much to learn.

“No other NMDA antagonist has the same effect, so ketamine has to be talking to another receptor,” said Schatzberg.

Looking down another pathway, Gordon also noted the investigation into a muscarinic agonist in combination with a peripheral antagonist that developed out of basic neuroscience research showing that muscarinic receptors might be important in psychosis.

Gains in genomic and epigenomics hold promise for defining the at-risk population and identifying drug targets, said Nemeroff. The epigenetic record can preserve evidence of early life trauma and psychiatric disorders that may explain why patients are more vulnerable to diseases of accelerated aging.

The cup of psychopharmacology may be half full or half empty at the moment, depending on your viewpoint.

“There’s a tendency in the field to lament the lack of progress, but a lot of progress has been made and will continue to be made,” he said. “A lot of psychiatric medications seem to help, and we need more, better tolerated drugs to help people, but there are limitations of success in all areas of medicine.”

Schatzberg sees two parallel paths to the future of psychopharmacology.

“It’s always good to be scientific and hope that leads to advances, but we still need serendipitous findings to open up the field,” he said. “So let’s do the science to understand the neural circuits and learn how drugs work. But let’s also do creative approximations of illnesses and take our shots and see what works.” ■

“The Behavior of Children Receiving Benzedrine” is posted

here.