A new transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) approach that compresses weeks of conventional TMS therapy into a few days can significantly reduce depression symptoms, according to the results of a pilot study published in AJP in Advance.

In this small open-label study testing the new Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy (SAINT) in patients with depression, 84% of the participants met the criteria for remission (defined as a score of 10 or less on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, or MADRS) after five days. Many of these patients remained in remission one month later.

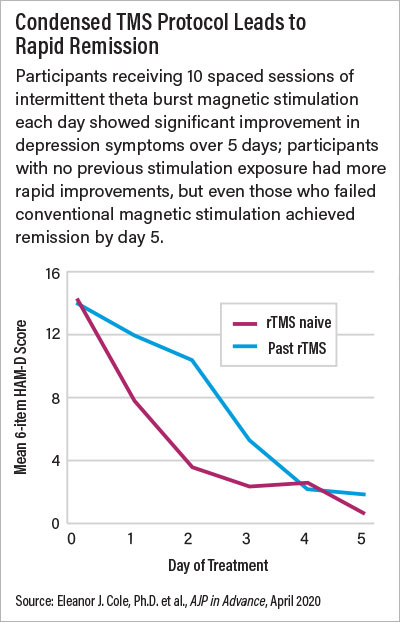

Most current TMS protocols involve delivering stimulation to patients for between 20 minutes and 30 minutes on a single day. The investigators from Stanford University and nearby Palo Alto University made use of a new form of TMS known as intermittent theta-burst stimulation, which can deliver therapeutic doses of magnetic energy in as little as three minutes. With this reduced time, the researchers could set up multiple sessions in one day.

The SAINT protocol involves 10 daily sessions, spaced 50 minutes apart. To further optimize the therapy, each participant received an MRI scan measuring brain activity after enrolling to pinpoint the location of a key brain circuit in the prefrontal cortex associated with depressive symptoms.

“The premise behind these repeated TMS applications is an established principle in basic neuroscience,” explained lead study author Nolan Williams, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University and director of the Stanford Brain Stimulation Laboratory. “It’s a concept known as spaced learning, which most people have probably benefitted from without even knowing.” An example of spaced learning is using flashcards to learn a new language, wherein a person reads the cards one by one and then picks them up an hour later to read them again.

For this study, Williams and colleagues recruited 22 adults aged 19 to 78, who were experiencing a moderate or severe depressive episode either due to major depression or bipolar disorder. All participants were required to have failed to respond to at least one antidepressant (some of the participants had also tried and not responded to conventional TMS). The researchers evaluated participants’ depression symptoms before and after each day’s 10 stimulation sessions. The participants also underwent cognitive testing before and after they completed the five, 10-session days to test for adverse cognitive side effects.

Twenty-one patients completed the 50 stimulation-session protocol, with 19 achieving remission. Average MADRS scores dropped from 35 to 5 after five days. Twenty of the participants completed a one-month follow-up, at which time average MADRS scores were about 11, with 60% of participants in remission.

There was no evidence of any cognitive problems following these repeated brain stimulation sessions, and the only side effects reported were fatigue and some facial muscle discomfort.

Williams noted that these findings come with all the caveats of a preliminary study: a small sample size, no placebo comparison, and the elevated expectations from patients receiving a new type of treatment. Still, he is optimistic about the potential applications of SAINT down the road.

The SAINT approach may be a good option for patients receiving care in an inpatient psychiatric unit, he said. According to Williams, only about 10% of psychiatric hospitals have electroconvulsive therapy, and almost none have TMS.

“On top of that, average inpatient stays keep getting shorter,” he said. “Therefore, a hospital would benefit from an intervention that works really fast and can maintain effects for that 30-day window after hospital discharge when suicide risk is really high.” A five-day SAINT regimen might fit the bill perfectly.

For patients who are not hospitalized, there is the outstanding question of whether five consecutive days of therapy would be too great a burden, Williams acknowledged. “This was a topic when I was applying for funding; people told me that no one is going to sit in a clinic all day for five straight days.” But based on the preliminary results, he doesn’t see time as an issue.

“Many of these participants with chronic illness said that if they had to take one week of treatment to get four weeks or months of relief, they would do it,” he said.

It’s also possible some patients might not need five straight days of treatment to experience symptom improvements, he added. “For the purposes of a clinical trial, everyone did the whole week, but about 30% of the participants achieved remission after just one day,” he said. The one-day responders were generally younger participants with less chronic depression and no previous experience with TMS.

More data are needed to determine the best options for patients, Williams said. He told Psychiatric News that a placebo-controlled study involving 30 patients has just been completed by his group, and they are ready to analyze the results.

The study was supported in part by Charles R. Schwab, the Gordie Brookstone Fund, the Marshall and Dee Ann Payne Fund, the Lehman Family, the Neuromodulation Research Fund, the Still Charitable Fund, the Avy L. and Robert L. Miller Foundation, Stanford, and a Brain & Behavior NARSAD Young Investigator Award. ■

“Stanford Accelerated Intelligent Neuromodulation Therapy for Treatment-Resistant Depression” is posted

here.