The Food and Drug Administration approval of

brexanolone last year was a watershed moment in psychiatry as it marked the first medication approved for postpartum depression. The arrival of brexanolone—which is a modified version of the natural hormone allopregnanolone—also reinforced the connection between mood problems and altered hormonal activity.

Brexanolone is far from the only hormone or hormone-manipulating compound that has been evaluated for the treatment of depression.

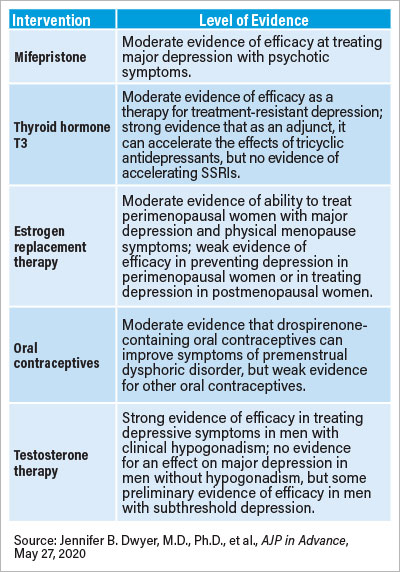

“While some treatments have largely failed to translate from preclinical studies, others have shown promising initial results and represent active fields of study in the search for novel effective treatments for major depression,” wrote the members of the APA Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments in a report published in AJP in Advance. The task force report explores the clinical evidence supporting therapies targeting three hormonal systems: the adrenal system, the thyroid system, and sex hormone system.

Sex Hormones

In addition to brexanolone, there are robust data to support the use of estrogen and testosterone replacement therapies in some patients with depression, the task force noted. Studies show that estrogen therapy may help reduce symptoms of depression in women during menopause. Similarly, studies suggest testosterone therapy is associated with mood improvements in depressed men with diagnosed hypogonadism (extremely low testosterone levels). Another hormonal treatment that has some supporting clinical evidence is the use of drospirenone (a progesterone-blocking oral contraceptive) to treat women with menstrual cycle–related mood problems, such as premenstrual dysphoric disorder, who do not respond to antidepressants.

Thyroid Abnormalities

The relationship between thyroid abnormalities and mood disorders is another area of research interest, the task force noted. Several clinical studies have demonstrated that the hormone triiodothyronine (known as T3) can both augment and accelerate the effects of older tricyclic antidepressants when given as an adjunct. There is no direct evidence (via a placebo-controlled study) that T3 can augment selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, but indirect data from meta-analyses comparing different depression treatments suggest T3 may benefit some people who do not respond to antidepressant therapy alone. There are limited data on how the other principal thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4) affects major depression, but several studies have shown that T4 is effective at treating patients with bipolar disorder who rapidly cycle between depressed and manic states.

Stress Response

The third system discussed was the adrenal-regulated stress response, which has seen a flurry of drug candidates over the years. The most promising candidate is mifepristone, a drug that blocks the receptor for cortisol. Though the data have been inconsistent, there is emerging evidence that this drug may reduce symptoms in patients with major depression with psychotic features. A recent review found that patients might need at least 1,200 mg of mifepristone daily to achieve symptom improvement. The task force noted that more research is needed to confirm mifepristone’s therapeutic potential.

Challenges of Endocrine Research

A target that has shown less success is corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), a hormone produced by the hypothalamus that initiates the stress response pathway. Despite much initial promise in animal studies, drugs aimed at inhibiting CRF or its receptors have not produced meaningful results in human trials.

“The CRF studies are a strong cautionary tale in the field of endocrine research,” said Jennifer Dwyer, M.D., Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University and lead author on the task force report. “The preclinical data were so clear and convincing but did not pan out. It illustrates the complexity of these hormonal systems.”

As Dwyer told Psychiatric News, all three of the systems reviewed feature sophisticated feedback mechanisms (in which the final hormone products regulate their own production) to ensure concentrations stay in a narrow range. Breaking that feedback loop to adjust hormone levels without causing unintended damage can be tricky.

Also as highlighted in the report, these hormones exert dramatically different effects depending on the patient’s age and the severity of his or her depression. While estrogen therapy is effective for depression in women during menopause, for example, there is no evidence it works in postmenopausal women. And in men without hypogonadism, testosterone has shown some efficacy to improve mild depression but has no effect in men with major depression.

Dwyer and colleagues on the task force underscored that with the exception of brexanolone’s indication for postpartum depression, none of these hormone formulations or hormone-targeting medications has been approved for any depressive disorder. “Over the next several years, the field will have a better sense of whether these exciting preliminary findings can be replicated in larger samples and applied to clinical practice,” they concluded. ■

“Hormonal Treatments for Major Depressive Disorder: State of the Art” is posted

here.