The past several decades have been marked by a nascent cultural reckoning regarding Indigenous societies. In the United States, however, the dominant (mostly Western, mostly European) culture has yet to make amends for hundreds of years of genocide, exploitation, and other trauma suffered by Indigenous groups. Unflinching explorations of the trauma and adversity perpetrated by the dominant culture remain aspirational, at best.

I thought that my allyship with Indigenous communities meant that I was further along in the reckoning process than the rest. After all, I had spent one subintern month working in a reservation medical clinic; I’ve spent the good part of two decades involved in Native American cultural events (attending pow-wows, providing medical and other support at yearly sundances, and establishing charter membership in the National Museum of the American Indian); and I have been involved in groups such as the Indigenous Native Child and Adolescent Committee of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. I even got certified as a diversity/equity/inclusion champion at my home institution, where I work with children from underserved communities, including Indigenous groups, who have been exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). But I am not affiliated with any tribe. I am the child of immigrants who both happen to be European. What I know about the historical trauma and adversity endured by the Indigenous population as a result of their oppression by the dominant culture I’ve learned indirectly through observation or through secondhand references (that is, primary sources of social science research).

In my work with traumatized individuals, I have investigated strategies for promoting well-being through recovery from adversity. Principles from the field of positive psychology have seemed most informative in providing constructs that could support emotional well-being in the aftermath of adversity. Two concepts that have resonated with me are those of resilience and salutogenesis.

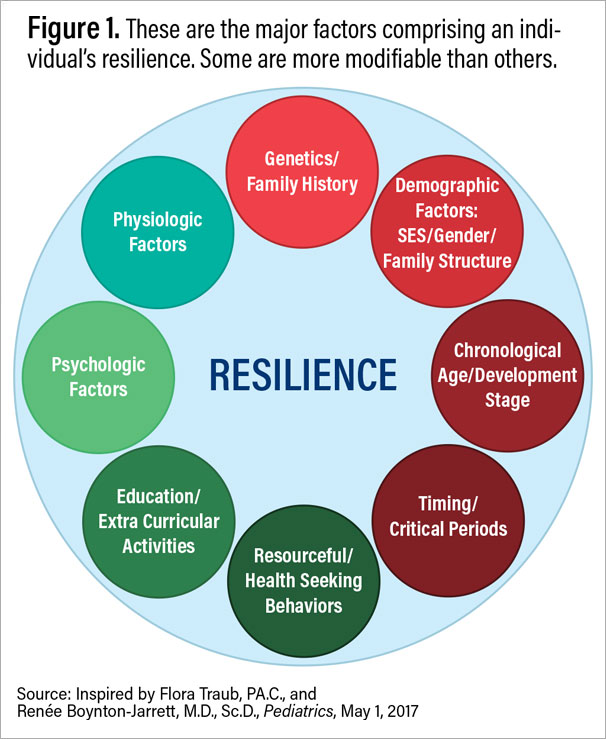

Resilience can be conceptualized as the ability to bounce back (with respect to one’s functionality in mind, body, and spirit) from toxic stress (the maladaptive psychological and physiological consequences of chronic exposure to ACEs). This ability is thought to be built upon numerous factors, illustrated in Figure 1 on facing page. Salutogenesis is defined as the process of achieving wellness “despite the trials and tribulations” of one’s life; this term was coined by Aaron Antonovsky, Ph.D., who concluded from his work with Holocaust survivors that a “sense of coherence” underlies a person’s well-being. A related concept is posttraumatic growth, where individuals can gain strength and wisdom from successfully coping with personal crises. What all of these concepts have in common is the expectation that negative stressors can produce positive change in an individual.

These constructs seem well-meaning, especially when the focus remains on individual members of communities who experience transgenerational transmission of trauma. However, these concepts also reflect a Western, or Eurocentric, emphasis on the individual that is not necessarily compatible with Indigenous and other ethnic groups that have a more communal orientation. In fact, it was recently pointed out to me that the concept of resilience can have negative connotations. There is the potential for re-emergence of the antiquated and false narrative that the individual is to blame for lacking the resilience that Western interventions are attempting to reconstitute; furthermore, the emphasis on individual resilience negates the contributions that the individual’s social and cultural systems can make in supporting recovery from trauma. There is strength and wisdom inherent in Indigenous communities that can be harnessed for healing. The community and the larger culture can provide resources that support well-being that Western positive psychology has not necessarily conceptualized. While the Western version of resilience emphasizes self-regulation as one mechanism for achieving individual well-being, a collectivist version broadens the scope of regulation to involve additional societal factors. The protective factors provided by Indigenous societal or cultural resources are wide ranging and emphasize co-regulation “to facilitate the ability to understand, express, and modulate thoughts, feelings, and behavior,” according to M. Tsethlikai, et al., in “Reflections on the Relevance of ‘Self Regulation’ for Native Communities,” published by the Department of Health and Human Services.

These include traditional childrearing practices, observing the actions of elders, engaging in traditional spiritual practices, participating in ceremonies, and upholding societal values. Additional approaches to advancing resilience with cultural humility include promoting community cohesion, advocating for decolonializing social narratives, and shoring up Indigenous sovereignty. To overlook these factors is to do yet another disservice to a marginalized and underserved but vital group.

I still believe in the power of salutogenesis. This belief is now tempered, however, by my appreciation of the need for a more culturally sensitive conceptualization of this construct. ■

I wish to thank Joshua Sparrow, M.D., for the inspiration for, and thoughtful feedback on, this manuscript.

“Reflections on the Relevance of ‘Self-Regulation’ for Native Communities” is posted

here.