In 1999, Julius Jones was sentenced to death for the killing of a White businessman in a case that some say was riddled with racial bias.

According to a September 2020 report by the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), “The Enduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the Death Penalty,” Jones was prosecuted under the administration of the late “Cowboy Bob” Macy, who sent 54 people to death row during a 21-year tenure as the Oklahoma County district attorney that was marked by extensive misconduct.

According to the report, “[A]n officer used a racial slur while arresting [Jones], prosecutors struck every Black potential juror but one, and one of the jury members used the n-word to describe Jones.”

The report added, “Jones’ court-appointed trial lawyers failed to call any of several available alibi witnesses, did not bother to cross-examine [a co-defendant who was given a substantially reduced sentence in exchange for his testimony against Jones], and did not call Jones to testify on his own behalf.”

The case of Julius Jones reflects the kinds of bias that experts, including forensic and general psychiatrists familiar with use of the death penalty, say is built into the entire structure of capital punishment—from pre-arrest to arrest, trial, and conviction or exoneration. “The death penalty is infected with racial bias at every stage of the process, and the effects of racial bias are cumulative,” Robert Dunham, executive director of DPIC, told Psychiatric News.

Dunham said that a host of factors preceding the trial phase ensure that people of color will disproportionately fill the ranks of death row: police practices in the community, charging practices of prosecuting attorneys, and geographical bias. These are compounded at trial by “aggravating circumstances” that are disproportionately applied to African American and Latino defendants, biased jury selection, and jurors’ racially biased perceptions of dangerousness (see box).

And for defendants with serious mental illness and/or a history of significant trauma and abuse—especially indigent Black and Brown defendants—the lack of a competent and thorough capital defense on the part of court-appointed defense attorneys can be decisive in defendants’ being sentenced to death.

According to DPIC, 185 death row defendants have been exonerated since 1972—because of police or prosecutorial misconduct, perjury or false accusation, false or misleading forensic evidence, inadequate defense, and/or DNA evidence. Of those, 115 have been Black or Latinx.

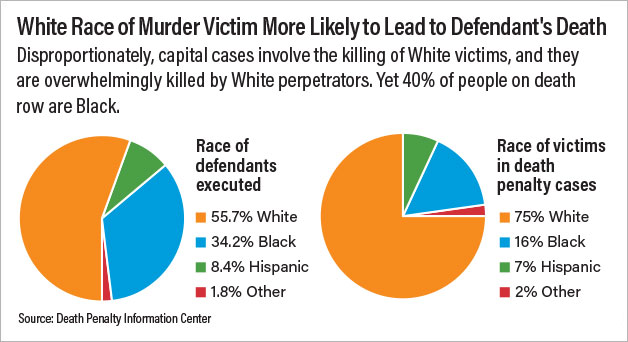

Since executions resumed in the United States in 1977, more White people (854) than Black people (524) have been killed by states, but those figures mask the fact that Blacks are vastly more likely to be on death row for the same crime committed by Whites. A signal feature of this disproportion is that the race of a victim is often determinative: since 1977, 295 Black defendants were executed for killing a White victim, and only 21 White defendants were executed for killing a Black victim (see graph).

“When you think about the cases police prioritize, they are cases that involve favored victims—a well-known victim or a victim who is part of whatever group in society is favored more,” Dunham said. “Disproportionally, the cases in the system involve the murders of White victims, and they are overwhelmingly killed by White perpetrators. Yet 40% of people on death row are Black—that is hugely out of proportion.”

Targeting the Vulnerable

The racial bias that infects capital punishment is rooted in a long history: The DPIC report links the attitudes that support the death penalty process rigged against people of color to the racist assumptions that supported lynching in the United States. Said Ngozi Ndulue, lead author of the report and senior director of research and special projects at DPIC, “We wanted to make that historical connection to show that alongside the racially biased structure of capital punishment, there are these standard background thoughts, attitudes, and expressions that are framed by our country’s history and continue to play a big role.”

Psychiatrist Joseph Thornton, M.D., has seen firsthand the arbitrary and racially biased way in which the death penalty is applied when he served from 1992 to 1996 as medical director at a Florida maximum security prison. There he personally visited 300 men on death row each week and learned their life stories.

In a January 2021 column in the Florida Times-Union, Thornton wrote that these stories “shine a light on a system that targets the most vulnerable—people with long histories of extreme trauma, neglect, poverty, and abuse.”

Thornton echoed Dunham in saying that the most important, overarching factor determining who lands on death row is not the crime itself, but geography: a small number of states account for the vast majority of capital deaths. “Look at where capital punishment happens—in states with a history of lynching,” Thornton said.

Thornton told Psychiatric News that within states, the jurisdiction of the district attorney—and that person’s zeal for recommending death—is decisive. Meanwhile, competent legal representation is not always available to the indigent Black and Brown defendants swept up into the machinery of capital punishment. After geography, Thornton said that “probably the most critical factor overall [in a defendant being sentenced to death] is having a zealous prosecutor and an incompetent capital defense.”

Thornton is submitting an action paper to the APA Assembly calling for APA to approve a position statement to support the abolition of capital punishment in 2022. Last year, the APA Board of Trustees approved the position statement titled “Issues Pertaining to Capital Sentencing and the Death Penalty” that called for a moratorium on executions.

Dunham noted that competent capital defense is especially important in the case of people with serious mental illness or a history of profound trauma—cases in which a murder may seem especially gruesome or senseless. “Those are the cases in which quality representation is critical, but an underfunded system for indigents does not always provide the best available experts to explain [to juries] really terrible conduct,” he said. “Race and poverty have a huge impact on this.”

Forensic psychiatrist Richard Dudley, M.D., explained that Supreme Court decisions and guidelines from the American Bar Association have made clear that in capital litigation, defense teams must develop a full social history based on collected records, documents, and information gathered from the defendant, family members, and others with intimate knowledge of the defendant.

That rarely happens, Dudley told

Psychiatric News (see

Expert Evaluation, Social History Key in Capital Defense Litigation). He is the author of the chapter “African Americans and the Criminal Justice System” in the APA Publishing book

Black Mental Health, edited by Ezra E. H. Griffith, M.D., Billy E. Jones, M.D., M.S., and past APA President Altha J. Stewart, M.D.

The death penalty will likely be abolished in time. Public opinion about capital punishment has shifted: A 2019 Gallup poll found, for the first time, that more people (60%) favored life sentences without parole for murder than the death penalty (36%).

Yet the persistence of capital punishment in the United States long after other developed countries have abolished it reflects an abiding belief that there are people whose crimes are so heinous that the only recourse is punishment by death. While the number of state executions has steadily declined, in the last year of the Trump administration, the federal government executed 13 individuals, some with horrific histories of trauma and abuse.

The endurance of the death penalty reflects, too, a faith that the criminal justice system can somehow finely distinguish those deserving death from other defendants whose crimes are less heinous.

The reality, born out in countless cases, is that capital punishment is a crude instrument, arbitrary and capricious but rigged against people already on society’s bottom rung and often nakedly political.

“Many people believe we have a magic system that gets it right perfectly, every time,” said Thornton. “But the death penalty is a lie. It’s really a political tool for politicians who want to claim they are tough on crime and are willing to kill for votes.” ■

“The Enduring Injustice: The Persistence of Racial Discrimination in the Death Penalty” is posted

here.

The APA position statement “Issues Pertaining to Capital Sentencing and the Death Penalty” is posted

here.

Information about the APA Publishing book

Black Mental Health is posted

here.

“Death Qualification in Black and White: Racialized Decision Making and Death-Qualified Juries” is posted

here.

“Looking Deathworthy: Perceived Stereotypicality of Black Defendants Predicts Capital Sentencing Outcomes” is posted

here.

An editorial by Thornton is posted

here.