There is broad agreement that current systems in the United States for responding to individuals in crisis not only do not work but have resulted in death. Jails are crowded with people who often have not even been accused of a crime but await psychiatric evaluation. Emergency departments cannot cope with the number of people seeking psychiatric or behavioral care for crisis and sometimes resort to “warehousing” of patients or even turning them away.

Many police officers feel that they are ill equipped to handle mental health crises and would rather focus on dangerous crime. Likewise, individuals in crisis and their loved ones cannot find meaningful help, often resulting in prolonged suffering, homelessness, and self-medication.

On July 16, a once-in-a-generation change is being launched regarding how America responds to people experiencing mental health or substance use crises. For the first time, they and their loved ones will be able to seek help through a simple, easy-to-remember number: 988.

And then what? Who will respond? Where will people go if they need more help?

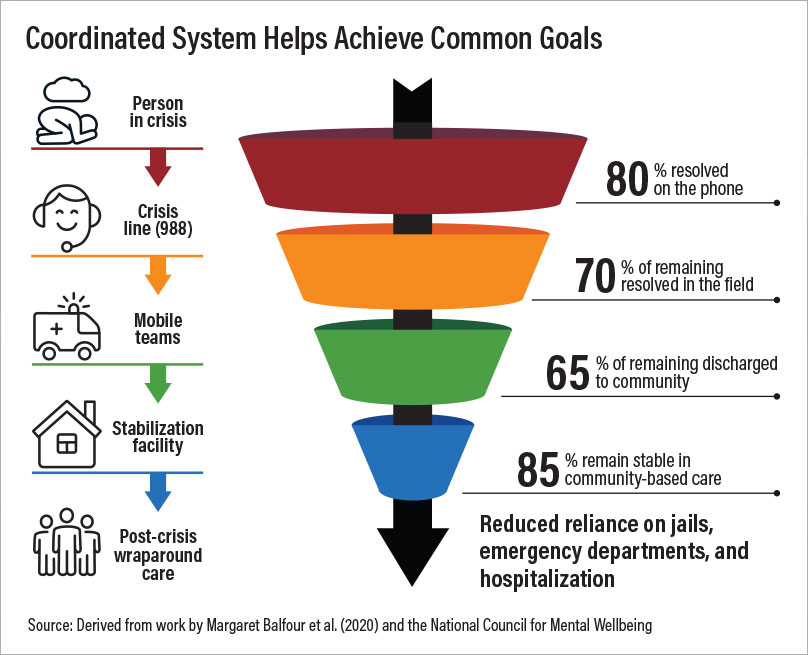

Ideally, those who dial 988 will be connected to a network of local and regional call centers that are part of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Operators trained in suicide prevention and crisis intervention can assess callers’ needs and determine what resources might be available and appropriate for them. If a local call center is unavailable or overwhelmed with calls, 988 callers will automatically be redirected to a national call center in an effort to keep wait times to a minimum. Experts estimate that approximately 80% of calls to 988 can be resolved over the phone.

What about the remaining 20%? According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), best practices indicate that three components of crisis response are needed for effective care: someone to call (such as 988), someone to show up (via mobile crisis response teams and similar co-responder models), and somewhere to go (often referred to as a crisis stabilization center, offering voluntary supports for up to 24 hours). Professional organizations and advocacy groups, including APA, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the Wellbeing Trust, and the Treatment Advocacy Center, have endorsed this approach. In his State of the Union Address in March, President Joe Biden called for $700 million to staff 988 and build out a broader crisis care continuum across the country.

Despite broad consensus and support for this model, it is nowhere near ready to be implemented in most parts of the country and requires much more funding than is under consideration. Oregon, however, is ahead of most other states for a number of reasons: It is one of a few states that have passed legislation supporting 988 and related services, and it is home to a key example of what works.

The CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets) program, in Eugene and Springfield, Ore., has gained such a significant profile for its non-police crisis response teams that it has become commonplace to refer to the concept of mobile crisis response as being “like CAHOOTS” (see

Bill Aimed at Replicating Oregon Mobile Crisis Program). It is one example of “someone to show up.”

CAHOOTS is a mobile crisis intervention program that was created in 1989 as a collaboration between White Bird Clinic and the City of Eugene. Its mission is to improve the city’s response to people who have a mental or a substance use disorder and/or are homeless. CAHOOTS is operated by White Bird Clinic.

In the wake of George Floyd’s murder, many policymakers began to focus attention on CAHOOTS and similar programs as a way to protect vulnerable or marginalized populations from police violence. If service calls for people experiencing a mental or behavioral crisis could be directed to mobile crisis response teams, the thinking goes, they could be connected with the resources they need, rather than encountering armed law enforcement officers.

Many law enforcement organizations agree, in principle, with this approach, having become exhausted by dealing with mentally ill individuals for whom they lack the training to serve well at the expense of focusing on the work they were intended to do. Such agreement, however tentative, is relatively rare in an era in which almost everything concerning law enforcement and public health has become politicized to the point of gridlock. In addition, mobile crisis teams are a solution that most policymakers appear to endorse.

Tim Black worked for CAHOOTS in a number of capacities, including as operations director and director of outreach and consulting for the White Bird Clinic. Black agrees that mobile crisis response teams can serve an important role in reducing the practice of asking police to respond to calls concerning people in crisis. Noting that a significant portion of the calls to which CAHOOTS responds originate as “welfare checks” (calls to 911 concerning the safety or well-being of a person, often a person in crisis), Black describes the variety of negative outcomes that mobile crisis can help people avoid, including citations, arrests, and incarceration.

Rather than taking a punitive approach to people exhibiting disruptive behaviors associated with crisis, CAHOOTS and similar programs start by attempting to get individuals’ basic needs met. “As a crisis responder, I often found that the people I encountered who were contemplating suicide were fundamentally dealing with homelessness,” Black said. “Once we could find a safe place for most of those people to lay down and get some sleep, and maybe a way to do their laundry and get some food, we often found that a person was past the point of crisis and could begin a path to recovery.”

Using a mixture of de-escalation techniques and counseling provided by a crisis intervention worker, providing basic medical care, and connecting individuals with voluntary resources in the community, experts estimate that 70% of calls to which mobile crisis teams respond can be resolved in the field. This means that given an initial volume of 1,000 calls to 988, as few as 60 people would be in need of transport to a facility.

“Somewhere to go” is the final component of the three-legged stool offered by SAMHSA’s best practices for crisis response. Under the current system, a staggeringly large number of people with mental illness are taken to jail, and not only do many fail to receive adequate care, their condition is often made worse.

Of course, not all individuals in crisis who have encounters with law enforcement officers are placed in jail. Many people are taken to hospital emergency departments by police or EMTs. But emergency departments lack both the capacity and the expertise to deal with individuals in crisis, which has led to the widespread practice of “boarding.” This has been detrimental to patients and staff and takes place at tremendous expense to the health care system. Worse still are reports of emergency departments turning away patients in crisis or patients being arrested by police to get them off the streets.

Progressing from the vision of a crisis response system laid out by SAMHSA and countless national, state, and regional entities to a robust and functional system requires continuous improvement and tremendous effort. Yet this system can reduce the harms experienced by individuals experiencing mental or behavioral health crises under the current system. If implemented carefully, it might even begin to heal the decades of understandable distrust and suspicion that many communities have had for crisis services. None of that is possible if there is a failure to enact all three of the components of crisis response: someone to call, someone to show up, and somewhere to go. As it stands, a once-in-a-generation opportunity could be squandered.

In addition to working with district branches to advocate for legislation supporting 988 implementation in states that have not yet done so, APA joined a coalition in March to drive awareness and support among state and municipal officials for the nationwide transition to the new 988 hotline. APA urges members in states that have not passed legislation to implement 988 to contact their district branch and get involved in advocacy on this issue. More information is available by emailing Erin Berry Philp at

[email protected]. ■