Women develop mood and anxiety disorders at significantly higher rates than men. Psychiatric illnesses in women are most common during the reproductive years and frequently overlap with reproductive transitions, such as menarche, the perinatal period, and perimenopause. In fact, 10% to 15% of women and birthing persons will develop perinatal depression, making it the most common medical complication of childbirth. In addition, mental illness is uniquely comorbid in many gynecologic conditions, including chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, female sexual dysfunction disorders, and urinary incontinence. Some primary psychiatric diagnoses, such as premenstrual mood syndromes and postpartum psychosis, are present solely in patients with female reproductive organ systems.

The complex interactions among reproductive biology and physiology, biopsychosocial factors associated with reproductive transitions, and psychiatric illness have historically fallen into a gap in modern medicine. Obstetrician-gynecologists, psychiatrists, family physicians, and pediatricians are all involved in caring for women’s physical and mental health, but because of varied training and scope of practice, a holistic approach to women’s reproductive mental health is difficult to achieve by an individual in any of these siloed specialties.

The comprehensive

Textbook of Women’s Reproductive Mental Health is a much-needed new resource that general psychiatrists can consult to broaden their expertise and better improve short- and long-term health outcomes in their patients who undergo female reproductive transitions. (Note that while there are individuals with female reproductive organs who do not identify as female, the bulk of the research thus far concerns women, and we will therefore use that term throughout this article.)

The textbook is a foundational resource in the discipline of reproductive psychiatry—the branch of medicine that encompasses the science and practice of treating mental, emotional, and behavioral disturbances related to female reproductive transitions. This field has seen an exponential increase in interest and awareness in the past 15 years. General residency programs can now benefit from the free online materials offered by the National Curriculum in Reproductive Psychiatry, and there are now 16 postresidency reproductive psychiatry fellowships in the United States and Canada. There has also been a growth in funding opportunities for research related to reproductive women’s mental health to fuel evidence-based practices, as well as a push for public policy growth and innovative collaborative care models. Hormonal fluctuation can trigger psychiatric illness in vulnerable women, and all psychiatrists should be educated in the risks that accompany the menstrual cycle and perimenopause. It is especially important for psychiatrists to develop skills for treating women in the perinatal period—a time when illness affects two generations and when many psychiatrists are reluctant to treat out of fear and lack of knowledge. This article will outline some important fundamental principles of perinatal psychiatry, including screening recommendations, diagnostic considerations, and treatment approaches.

Screening for Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders

Any clinician who treats perinatal women, including obstetrical, primary care, and mental health professionals, should be screening for depression and anxiety. Major professional organizations including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Pediatrics, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and others recommend universal screening for depression during pregnancy and postpartum, as this strategy has been shown to reduce prevalence of depression and increase remission rates in a large systematic review by Elizabeth O’Connor, Ph.D., and colleagues published January 26, 2016, in JAMA.

The most common screening tool is the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), which is validated for pregnant and postpartum patients and available in over 60 languages. While the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Healthcare recently recommended against screening perinatal patients, their recommendation implies that health care professionals are routinely asking patients about their mental health during visits, which may not always be the case due to limited time, comfort level, and training. Their recommendation also highlights the gaps in access to psychiatric services in Canada. Most perinatal experts, however, believe that screening and identifying perinatal patients in need of psychiatric care is crucial not only to identify patients in need but also to further highlight the lack of infrastructure and encourage policy changes that may improve access.

Screening helps to identify patients at risk or with concerning symptoms who need further clinical evaluation (Figure 1). An elevated score alone does not indicate an underlying disorder, but rather provides information to detect, treat, and improve outcomes for women. While there are significant barriers to treatment, including transportation, child care needs, and stigma associated with mental health treatment during the perinatal period, screening may help to begin a conversation about maternal mental health, especially for members of racial and ethnic minorities who experience significant health care disparities.

Risk-Risk Analysis: A Framework for Treating Perinatal Patients

Nearly all psychiatrists will treat patients prior to and during pregnancy and should be familiar with key aspects of treating women with perinatal mood disorders (Table 1). Ideally, psychiatrists and patients should collaborate to develop a treatment plan prior to conception, but because close to 50% of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned, this is not always possible. Therefore, we recommend that psychiatrists begin discussions early about plans to become pregnant, re-address plans for pregnancy over time, inquire about contraceptive use, discuss medication safety and what steps to take regarding medication continuation/discontinuation, and err on the side of using medications with more reassuring safety profiles for women of childbearing age. During preconception planning or if the patient is already pregnant, the psychiatrist and patient must use shared decision-making, weighing the risks of untreated or undertreated psychiatric illness against the possible risks associated with psychotropic medications to the mother and the fetus. This is formulated as a risk-risk analysis and is an important clinical tenet of reproductive psychiatry (Table 2). These discussions can be further augmented by consultation with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist obstetrician prior to or during pregnancy.

A risk-risk discussion includes a thorough diagnostic evaluation to ensure the validity of a psychiatric diagnosis. When patients present with preexisting diagnoses and medication regimens, it is important to obtain diagnostic clarity to have the most informed risk-risk discussion. Assessing the severity of illness and presence of residual symptoms may also inform the treatment plan and risk for relapse in the perinatal period.

The evidence regarding psychotropic medication safety relies mostly on observational data, as randomized, controlled trials have not been performed due to ethical concerns about randomizing vulnerable subjects. Early studies regarding the risks of antidepressants during pregnancy did not appropriately control for confounders or compared medication users with healthy controls, which is not an accurate comparison group. Since women with mood disorders (and psychotropic medication exposure) are more likely to have other medical and psychiatric comorbidities, as well as psychosocial contributors, these comorbidities need to be considered when assessing study outcomes. As study designs improved, including controlling for confounders and using appropriate control groups, most risks of psychotropic medications were determined to be lower than initially thought. There is clear evidence regarding the risks of untreated psychiatric illness during pregnancy, and this risk must be weighed against known risks of psychotropic medications.

Historically, because the risks of psychotropic medications were overestimated and the risks of untreated psychiatric illness underestimated, recommendations were to discontinue psychotropic medications during organogenesis in the first trimester or throughout pregnancy. This left women with a history of psychiatric illness at high risk for symptom relapse during pregnancy and in the postpartum period. Now, the increased volume of data related to the reproductive safety profile of psychotropic medications and outcome data for untreated psychiatric illness provide a framework for psychiatrists and patients to weigh the risks of both untreated psychiatric illness and psychotropic medication use in the perinatal period. We include a potential risk-risk analysis in Table 2 for a patient with depression, comparing data about untreated depressive illness versus treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, each risk-risk discussion is patient-specific and may be affected by severity of psychiatric illness, socioeconomic status, racial disparities, psychosocial support, and/or access to treatment modalities.

Determining Etiology of New-Onset Psychiatric Episode

Ms. A is a 27-year-old woman with no prior psychiatric history presenting three weeks after the delivery of her first child. She is married with a supportive husband who works full time and has minimal family support outside of her husband. She noted some increased worry throughout the pregnancy, specifically related to the health of her baby, which affected her sleep. At 37 weeks, she was induced due to concern for preeclampsia and had an emergency C-section after her labor failed to progress and the baby was showing signs of distress. She now reports increased crying spells, low mood, and anxiety specifically related to the baby. She is sleeping one to two hours at night and waking up frequently to check if the baby is breathing or to clean bottles and pumping parts. Her partner reports that she is not acting like herself. She is attempting to breastfeed, but the baby had difficulty latching so she is mostly pumping breastmilk. She notes thoughts of harming the baby, such as dropping him from the changing table or falling down the stairs while holding him. She worries that she is a bad mother and contemplates whether her family may be better off without her.

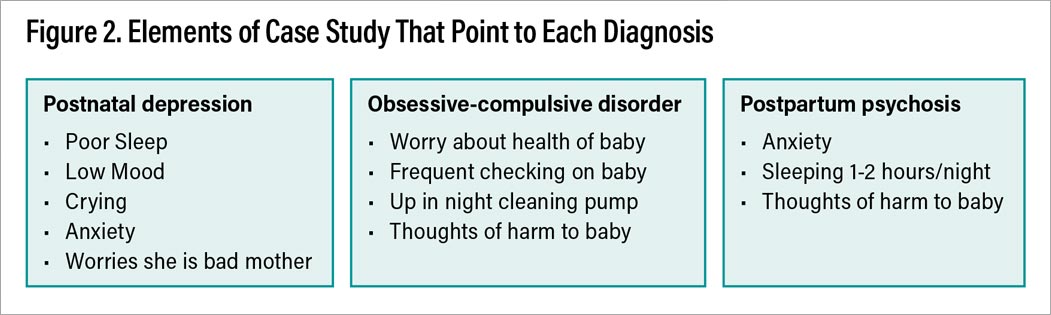

To unpack the case study above involves consideration of a number of potential differential diagnoses. In addition to medical diagnoses associated with postpartum mood changes, such as new-onset hypothyroidism (arising from postpartum thyroiditis or from Sheehan’s syndrome secondary to postpartum hemorrhage), a broad range of psychiatric conditions must also be considered, including postpartum depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and postpartum psychosis (PPP). It is vital to differentiate mood disorders in the perinatal period, as symptoms often overlap and management varies depending on the underlying diagnosis, as summarized in Table 3. For example, intrusive thoughts, particularly of harm coming to the baby, can be nonpathological—most new mothers experience them. But they can also be present in depressive disorders, GAD, OCD, and PPP. Irritability is seen in baby blues, mania, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

For the case of Ms. A, we will outline the three most likely diagnoses—perinatal depression, OCD, and PPP—and cover diagnostic and treatment considerations for each.

Perinatal depression

Perinatal depression is common, affecting at least 15% of women, and encompasses both antenatal and postpartum symptom onset. (Pregnancy-onset depression is likely a biologically separate disorder from postpartum-onset depression, but DSM-5 does not make this distinction.) The symptoms of perinatal depression are similar to the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, including low mood, anhedonia, low energy and motivation, poor concentration, changes in sleep or appetite, and suicidal ideation when severe. Since fatigue and changes in sleep and appetite are common in the perinatal period, it is essential to discern a mood episode versus symptoms related to pregnancy. Anxiety and intrusive thoughts are more common in perinatal depression, with frequent ruminations related to the health of the mother or baby.

Treatment

Treatment includes SSRIs, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), all of which are compatible with pregnancy and lactation. Dosage increases may be necessary due to physiologic changes, and there is no evidence to support the practice of lowering or stopping medications in the third trimester to decrease the risk of neonatal adaptation syndrome.

Unipolar versus bipolar perinatal depression

A full discussion about the management of bipolar disorder in the perinatal period is beyond the scope of this article, though close to a third of women with bipolar disorder first present in the perinatal period. The majority of postpartum mood episodes experienced by those with bipolar disorder are depressive episodes. It is therefore important to screen for both postpartum depression and bipolar disorder to avoid misclassifying bipolar depression as unipolar depression. In fact, Lindsay Merrill, M.D., and colleagues, as outlined in the August 2015 issue of the Archives of Women’s Mental Health, found that 21.4% of women who had a positive EPDS screen (score > 10) at their initial prenatal visit also had a positive Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Similarly, Katherine L. Wisner, M.D., M.S., and colleagues, reported in the May 2013 issue of JAMA Psychiatry that 22.6% of postpartum women with a positive EPDS screen were diagnosed with bipolar disorder upon structured clinical interview. Identifying an underlying bipolar illness greatly shapes management both in the short and long term and thus is essential not to miss during this period of increased vulnerability.

OCD

New-onset or an exacerbation of OCD is common in the postpartum period, with higher rates than in the general population. Symptoms include obsessions (intrusive thoughts or images) and/or compulsions (repetitive behaviors completed to minimize anxiety) that are time consuming and affect functioning. During pregnancy, obsessions are often related to contamination or thoughts of infant harm. Compulsions may include excessive cleaning (such as sterilizing bottles/pumping supplies excessively) or checking behaviors (such as checking if the baby is breathing). The thoughts of infant harm are ego-dystonic and cause significant anxiety or distress for the mother; they may even lead to avoidance of the infant or environment where harm could occur. To ensure that unnecessary hospitalization and separation from the newborn are avoided, screening should further delineate intrusive thoughts of infant harm versus delusional thoughts (as discussed on facing page with PPP).

Treatment

As in the general population, treatment includes cognitive-behavioral therapy (specifically exposure-response prevention) and pharmacologic treatment with high-dose SSRIs as first-line treatment and TCAs or other antidepressants as second line. Second-generation antipsychotics may be appropriate augmentation in treatment-resistant cases. Treatment considerations include dosage titration, as women may require higher doses as pregnancy progresses due to the physiologic changes of pregnancy. At this time, there are no data to suggest that higher doses of SSRIs are associated with worse maternal or fetal outcomes; fear or anxiety regarding increasing doses should be discussed with the patient.

Postpartum Psychosis (PPP)

When evaluating patients with new-onset postpartum mood symptoms, it is vital to rule out PPP. While rare, PPP is associated with an increased risk of suicide and infanticide and thus is considered a psychiatric emergency. The onset of symptoms typically occurs within the first four weeks after delivery, and they can include both mood (such as mania or depression) and psychotic symptoms (including delusions about childbirth or the infant). Symptoms wax and wane, and patients can appear delirious, with new-onset confusion, alterations in sensorium, and disorganized thought. PPP can also include delusions regarding infanticide, and thoughts of infant harm must be differentiated from intrusive thoughts related to OCD. As outlined in Figure 2, thoughts of infant harm in PPP include delusional content and poor insight and are ego-syntonic (congruent with personal beliefs), while in OCD thoughts are intrusive and ego-dystonic (incongruent with personal beliefs) with intact insight.

Treatment

Treatment consists of identifying PPP, assessing safety, ruling out medical causes of delirium or change in mental status, and inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. During hospitalization, lithium is the recommended first-line treatment, and studies have shown that the vast majority of patients respond to lithium. Benzodiazepines and antipsychotics are useful adjuncts, but they can usually be discontinued after the acute period. Electroconvulsive therapy can also be used when patients have severe symptoms, when rapid recovery is necessary, or when patients have not responded to other treatments. Treatment should be continued for at least nine months after an episode. PPP is closely linked to bipolar disorder and may represent a first episode or recurrence of an underlying bipolar illness, which may affect treatment decisions related to maintenance management. A minority of women who experience PPP have episodes only in the postpartum period and do not have an underlying bipolar disorder. After one episode, it is impossible to know whether women will go on to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, but in either case, it is crucial to counsel all women who experience PPP about prophylactic treatment in subsequent peripartums. Lithium has the strongest body of evidence for prophylaxis against another episode of PPP.

Conclusion

Reproductive psychiatry is an emerging and urgently needed area of clinical interest, education, and research. The Textbook of Women’s Reproductive Mental Health provides a guide and clinical toolkit for treating women during high-risk reproductive transitions. We hope that this book serves as a tool for trainees and psychiatrists when encountering women across the lifespan, including at menarche, across the menstrual cycle, in the perinatal period, and in perimenopause. As access to trained reproductive psychiatrists is limited, we hope that improved educational resources will reduce gaps in care and improve physical and mental health outcomes for women during these vulnerable time periods.

While this book and other similar efforts are a good start, there are still substantial gaps in knowledge in reproductive psychiatry. We need research on etiology and pathophysiology, and we especially need research that can inform diagnostic and treatment considerations for LGBTQ+ patient populations, transgender/genderfluid individuals, and women affected by racial and socioeconomic disparities. And, given the continued nationwide shortage of psychiatrists, funding for implementing evidence-based collaborative and integrated care models could vastly improve access to care and should be a priority for all health systems. ■

Author Disclosure Satement

Lauren M. Osborne, M.D., receives royalties from APA Publishing and Elsevier, funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, and funding from the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology for the development of the reproductive psychiatry curriculum. The other authors have no disclosures.