Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is psychiatry’s forgotten disorder. Despite its enormous cost to individuals, families, and society, few clinicians diagnose ASPD, let alone offer treatment, and few researchers investigate it. Clinicians and researchers have largely distanced themselves from the disorder, perhaps in sympathy with family members and friends who react similarly.

Psychiatry has wrestled with the problem of chronic antisocial behavior for more than 200 years. While the terms and definitions used have shifted over the years, they all describe recurrent, serial misbehavior. People with ASPD rebel against authority, resist all norms, and push the limits of acceptable behavior. Nineteenth century British physician William Pritchard used the term moral insanity to describe people who willfully engage in antisocial conduct. His use of the term moral was prescient considering that many people he described appeared to lack a moral compass, perhaps ASPD’s most disturbing aspect.

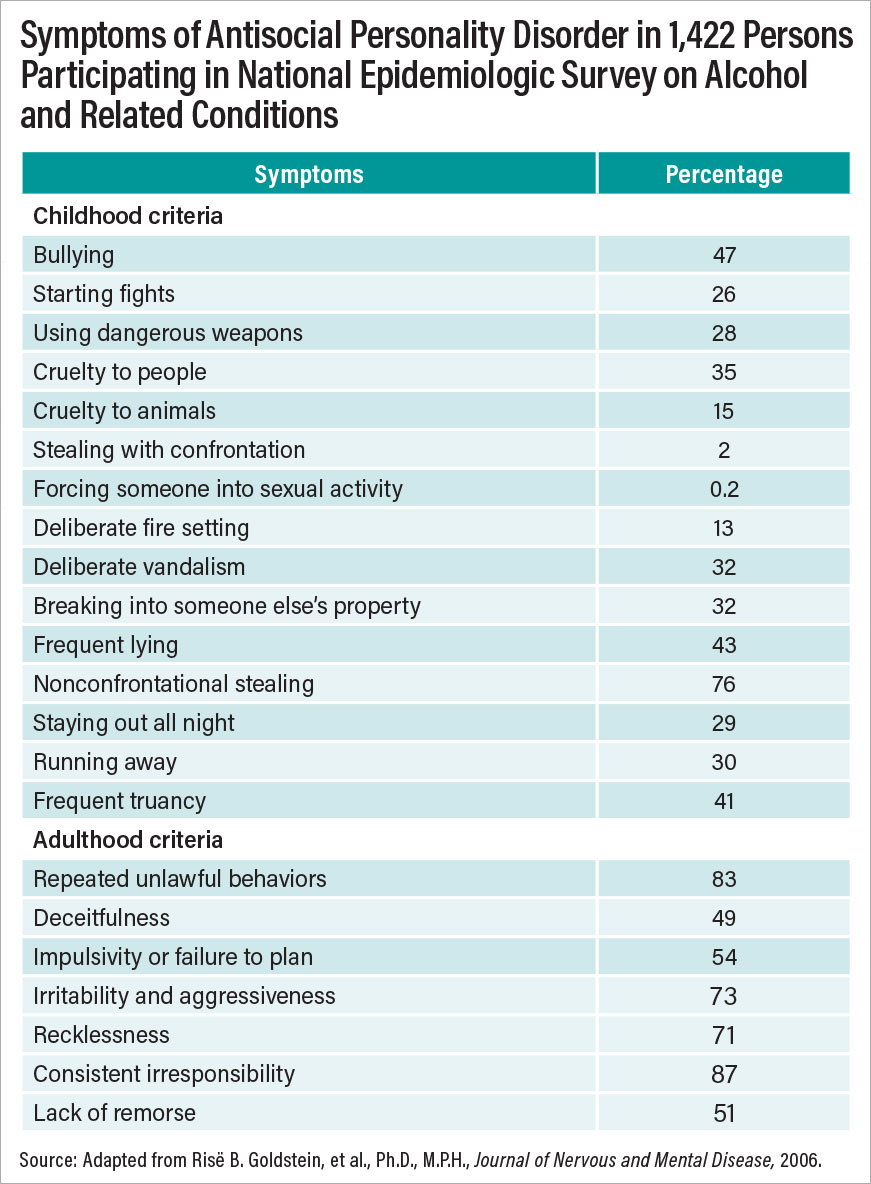

Poorly understood even by psychiatrists and psychologists, ASPD was given one of the best definitions by the Donald Goodwin, M.D., and Samuel Guze, M.D., in the book Psychiatric Diagnosis. They described ASPD as “a pattern of socially irresponsible, exploitative, and guiltless behavior manifested by disturbances in many areas of life including family relations, schooling, work, military service, and marriage.” Behaviors include criminal acts and failure to conform to the law, failure to sustain consistent employment, manipulation of others for personal gain, and failure to develop or sustain stable interpersonal relationships.” Symptoms fall along a spectrum of severity and range from relatively mild at one end—for example, lying, cheating—to very serious at the other—for example, rape and murder (see table). Other important attributes include lack of empathy for others, lack of remorse, and failure to learn from the negative results of one’s behavior.

Work by Lee Robins, Ph.D., and others in the 1950s and 1960s strongly influenced the ASPD criteria created for DSM-III in 1980. They have since been refined for subsequent DSM editions, but they remain true to Robins’ vision of a chronic behavioral disorder beginning in childhood. DSM-5 criteria require that a person have three or more of seven pathological personality traits (for example, deceitfulness, impulsivity, irritability or aggressiveness, recklessness, and irresponsibility). The person must be 18 years or older and meet criteria for conduct disorder prior to age 15. Schizophrenia and mania have been ruled out as a cause of the symptoms. ASPD is the only disorder in DSM-5 with an age requirement. While the criteria were criticized from the outset for ignoring psychological components of the disorder, Robins argued that a focus on behavioral symptoms would lead to greater diagnostic reliability.

Comorbid Disorders Common

Common and culturally universal, surveys in the United States and United Kingdom show that 2% to 5% of the general adult population in the United States meet the criteria for lifetime ASPD. Prevalence in men is from 2 to 7 times that in women, depending on the sample surveyed and assessment method used. The disorder rarely occurs by itself; usually it is associated with high rates of substance use disorders, mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), pathological gambling, and other personality disorders (borderline and narcissistic personality disorders). Rates of suicidal behavior and completed suicide are elevated.

The following vignette illustrates many of the typical symptoms of ASPD and how they affected one of our patients over a lifetime. The patient had been admitted to the University of Iowa Psychopathic Hospital (now Psychiatric Hospital) in the 1950s and was followed up over 30 years later in the 1980s (see Donald W. Black, M.D., and Nancy C. Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D.,

Introductory Textbook to Psychiatry, Seventh Edition, APA Publishing, 2020).

Case Study 1

Burton, age 18 years, was admitted for evaluation of antisocial behavior at the request of his adoptive parents. His early childhood had been chaotic and abusive. His alcoholic father had married five times and abandoned his family when Burton was 6 years old. Because his mother had a history of incarceration and was unable to care for him, Burton was placed in foster care until he was adopted at age 8. As a child, Burton lied, cheated at games, shoplifted, and stole money from his mother’s purse. He was sent to a juvenile reformatory at age 16. While there, he slashed another boy with a razor blade in a fight. In the hospital, the psychiatrists interviewed Burton and his adoptive parents, conducted an encephalogram (deemed normal), and measured his IQ at 112. He showed no interest in psychotherapy, insulted staff members, and left abruptly after a 16-day stay. He was described as “unimproved” on discharge.

Burton was followed up 30 years later at age 48. Burton, appearing old and haggard, was living in an impoverished neighborhood in a nearby community. He admitted to more than 20 arrests and five felony convictions on charges ranging from attempted murder and armed robbery to driving while intoxicated. He had spent more than 17 years in prison. Burton reported nine hospitalizations for alcohol detoxification, the most recent occurring earlier that year. Burton had never held a full-time job and had lived in six states; he had moved more than 20 times in 10 years. Burton’s common-law marriage was described as unsatisfactory, and he admitted committing spousal abuse. He occasionally attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings but otherwise did not socialize. When asked, Burton admitted that he had not yet settled down and still got a “charge out of doing dangerous things.”

Longitudinal studies show that ASPD is worse early in its course but that its symptoms lessen with advancing age. While the older antisocial person may be less troublesome to families and society, improvement follows many years of behavioral symptoms that have stunted educational and work achievement, thereby limiting the person’s potential and contributing to unstable relationships and family discord. The following case vignette is illustrative.

Case Study 2

Mr. C, age 28, was admitted to the University of Iowa Psychiatric Hospital for evaluation of “lack of drive and ambition” and inability to find security and happiness, but the doctors quickly noted his history of stealing, absenteeism from work, and inability to hold a job as suggestive of an underlying ASPD.

Mr. C grew up in a two-parent, solidly middle-class home. His misbehaviors started around age 5 years, when he first ran away from home. At age 6, he started a fire in a shed, and by age 11, he was regularly stealing money from his mother’s purse. Mr. C managed to finish high school with middling grades and started college, but he would skip classes and eventually dropped out. At age 20, he broke into a local drugstore but tripped an alarm and was caught. A guilty plea led to his first jail sentence. Mr. C joined the army where he served six years; however, he was court-martialed for stealing money from a superior officer’s trousers and was dishonorably discharged from the service. After the discharge, he returned home and married after a brief courtship. His wife knew nothing of his past. The family moved to California (he and his wife had one child by then) seeking new opportunities but failed to find work, and in a quixotic move, he stole a car with the plan to drive back to Iowa. He was quickly apprehended, pleaded guilty, and received probation. His criminal career continued, mainly involving breaking and entering, to supplement, he said, his meager income from his work as an unskilled laborer.

At the hospital, a physical examination showed only obesity and mild hypertension, and Mr. C’s mental status was deemed normal. He was offered individual and group psychotherapy, a standard approach at the time, and remained five months. At discharge, he was thought to have a “poor” prognosis.

Mr. C was followed up at age 65. By then, he was living in a small apartment in a small rural community. He reported that he was lonely, as his wife had passed away, and he was estranged from his three children. He had a part-time job with an insurance agency and had worked there for 25 years. In the intervening decades, Mr. C claimed only an additional two arrests, but his “rap sheet,” which was public information, revealed a much different story, with multiple arrests and incarceration for mainly minor nonviolent offenses. Mr. C felt that the lengthy psychiatric hospitalization had helped him grow as a person and that he had genuinely improved, attributing much of that to the influence of his loving wife. He reported regular church attendance and socialized with his neighbors.

Genetic, Neurobiological, and Environmental Causes

Considered a multidetermined disorder, not unlike schizophrenia or hypertension, the cause of ASPD is thought to involve both genetic vulnerability and environmental events. Early family, twin, and adoption studies have suggested a heritable component, yet exactly what is inherited and how the disorder is transmitted remain unclear, even as newer genetic methodologies are being applied.

Competing theories suggest that ASPD results from the consequences of a neurodevelopmental insult, chronic underarousal, or deficient cognitive processing. Roles have been proposed for the neurotransmitter serotonin and the hormone testosterone, each known to mediate aggression, and, in the case of serotonin, impulsivity.

Numerous structural brain imaging studies have been conducted on individuals with ASPD, examining a wide range of brain regions. Overall, studies have documented that ASPD likely has a neurobiological basis involving structural brain abnormalities, with key impairments commonly found in the prefrontal and temporal cortices. These findings are bolstered not only by results derived from functional imaging studies but also from neuropsychological studies that document executive functioning deficits in populations of individuals with ASPD. Indicators for limbic dysfunction that are associated with ASPD can be observed early in life. Accumulating evidence also suggests that structural brain abnormalities are able to improve the prediction of ASPD when considered alongside psychosocial risk factors for antisocial behavior, are influenced by both genetic and social environmental factors, and can help to account for why males have higher rates of ASPD.

A review of imaging studies, however, suggests that there is a diversity of findings in individuals with ASPD. Future studies that account for psychiatric comorbidity and other confounding effects may help to reduce some of the observed heterogeneity in these structural imaging findings. More neurobiological testing in prospective longitudinal studies, as well as the inclusion of female subjects and larger samples in structural MRI studies of ASPD, can also help advance our understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of this personality disorder.

Likewise, environmental events that could be involved in the onset or maintenance of antisocial behavior include childhood abuse, poor parenting, and disturbed peer relationships. A history of childhood abuse occurs at high rates in antisocial persons, many of whom visit the abuse on their own children, thus perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of abuse. Erratic or inappropriate parental discipline and inadequate supervision have all been linked to antisocial behavior. Many antisocial persons grow up in households where one or both parents were antisocial, unable to effectively monitor their child’s behavior, set rules and ensure that they are obeyed, check on the child’s whereabouts, or steer the child away from troubled playmates. Disturbed peer relationships (the “birds of a feather” phenomenon) are often overlooked as a possible contributing factor but are present in the history of most antisocial persons. Unhealthy relationships often take root during the elementary school years and reward aggressive behavior, in the process encouraging gang membership in which troubled youth can gain a sense of belonging.

An unresolved question concerns the matter of whether frontal lobe dysfunction in antisocial populations is due to head injury, disrupted prenatal development, or other causes, such as neurological illness.

Antisocial persons are overrepresented in psychiatric clinics and hospitals, though rarely seek care for their ASPD (and are likely unaware that they have it). Instead, they typically seek care for co-occurring depression, substance misuse, problems relating to marital maladjustment, anger and irritability, and/or suicidal behavior. Because there are no diagnostic tests, the ASPD diagnosis rests on the person’s history of chronic and repetitive behavioral problems dating back to childhood or early adolescence. The differential diagnosis includes other personality disorders (especially narcissistic and borderline personality disorders), substance use disorders, psychotic and mood disorders, intermittent explosive disorder, and medical conditions that might cause violent outbursts (for example, temporal lobe epilepsy).

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors do not fully determine the emergence of antisocial behavior, and neither do biological factors. The antisocial syndrome has a complex etiology, involving genetic and environmental interactions. Thus, a dysfunctional family, parental maltreatment, and a dangerous neighborhood might increase the risk for antisocial behavior but are not fully predictive of the disorder. Children with antisocial traits might react with aggressive behavior to any or all of these stressors, but children with a different trait profile (for example, one marked by introversion) might not.

An antisocial child who retains the same traits in adulthood is a bit like a pit bull—dangerous when stressed or deprived, yet capable of companionship when the environment is stable, predictable, and sympathetic. That said, children with a genetic predisposition who experience serious environmental adversities are primed to develop ASPD. Although neither ingredient is determinative, it is the combination that “cooks” the disorder.

Treatment Guidance

The psychiatric treatment needs of people with ASPD should be addressed in outpatient settings. There is usually little reason to psychiatrically hospitalize antisocial people, and they can be disruptive to the ward milieu. Exceptions include crisis stabilization for recent (or imminent) suicidal behavior, recent (or threatened) violent or assaultive acts, and/or monitoring of alcohol or drug withdrawal. Patients should be discharged when the crisis has passed.

The view of many mental health professionals is that ASPD is untreatable. This conclusion is clearly premature because of the lack of relevant research for either medication or psychotherapy to guide treatment decisions. Clinicians are largely on their own to sift through the literature searching for treatment studies. No medications are FDA approved or routinely used to treat patients with ASPD. While medications are sometimes used to treat patients for aggression and irritability, their use is off-label. These medications include lithium carbonate and other mood stabilizers, antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics. Response to medication is variable, and while some patients improve, others fail to improve at all. When improvement occurs, it tends to be partial, so that improvement may mean only that the individual has fewer outbursts or has a “longer fuse” that gives the person more time to reflect before lashing out.

Importantly, medication can be targeted at the patient’s co-occurring disorders. Mood and anxiety disorders are common, and antidepressants might be relevant to their treatment. Similarly, co-occurring bipolar disorder can be treated with mood stabilizers or atypical antipsychotics. Because benzodiazepines can be disinhibiting, as well as habit forming, their use is not recommended. Likewise, stimulant medications for co-occurring ADHD should be avoided. Instead, nonaddicting alternatives such as bupropion, clonidine, or atomoxetine should be used. Evidence suggests that successful treatment of co-occurring disorders has the potential to reduce the person’s antisocial behavior.

Several psychosocial interventions have been tested in patient samples that include antisocial persons. These include cognitive-behavioral therapy, mentalization-based treatment, contingency management, psychoeducation, skills training, and motivational interviewing.

Taken together, these studies suggest that significant positive changes occurred in ASPD and warrant further research. Moreover, there is no evidence that treatment makes people with ASPD worse, as has been alleged.

Conclusion

ASPD is common, problematic, and costly to society. Infrequently diagnosed, people with ASPD are rarely referred for treatment of the condition, though they are often seen by mental health professionals for their co-occurring disorders, anger and irritability, domestic problems, and/or suicidality. ASPD begins early in life and is typically chronic and lifelong, with a trend toward improving as the individual ages. But even if the individual improves, the damage has been done, as antisocial persons fall behind their non-antisocial peers in their educational achievement, income, and career success. ASPD most likely results from the interplay of genes and environment.

Mental health professionals will continue to struggle to help those with ASPD until researchers develop empirically based treatments. Most likely, future treatment recommendations will involve a combination of medication to target anger, irritability, and other antisocial symptoms, while psychotherapy can be used to address the cognitive and moral aspects of the disorder. ■

Author Disclosure Statement

Donald W. Black, M.D., has received royalties from APA Publishing, Oxford University Press, Merck, and Kluwer Wolters; consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim; and honoraria from Medscape.