Some months ago, I wrote an article for this

column about the removal of Lord Horatio Nelson’s (1758-1805) statue from a public square in Barbados. The political decision to uproot artistic evidence of the country’s long history of being colonized had generated much commentary throughout the island about dignity and identity. I ended the column with a reference to the Caribbean Nobel winner Derek Walcott, who had chastised Caribbean peoples for their envy of European statues and had urged them to contemplate the beauty of the Caribbean and other matters more relevant to their modern lives.

In my most recent trip to Barbados, just about everybody urged me to visit the Golden Square Freedom Park. It was obvious that the creation of the park was an event that had galvanized a return to families and friends interrogating themselves about their roots, the meaning of their country’s independence from colonial masters, and who and what should be celebrated. Nelson was not even an afterthought in any of these discussions. I learned that in 1999, the Ministry of Education and Culture commissioned a group to develop a project that would celebrate individuals who had contributed to the island’s overall development. From my discussions, I understood this to include “unsung heroes” like the Amerindians who had inhabited the island before the arrival of the first British settlers, the indentured servants who were members of the island’s labor force, and the African enslaved persons and their descendants who had made contributions to the island’s progress.

The two-acre park rests a stone’s throw away from the site previously occupied by the Nelson statue in Bridgetown, the capital city. The park’s inauguration occurred on November 29, 2021, a day before the island’s transformation into a parliamentary republic. We should remember that Barbados became independent from Great Britain on November 30, 1966. It is with these dates in mind that I reflected on friends’ urging me to visit the new space. Many of them were enthusiastic about describing their impressions and providing background information. Construction of the Freedom Park required demolition of several buildings that previously occupied the site. Not everybody was pleased with the decision.

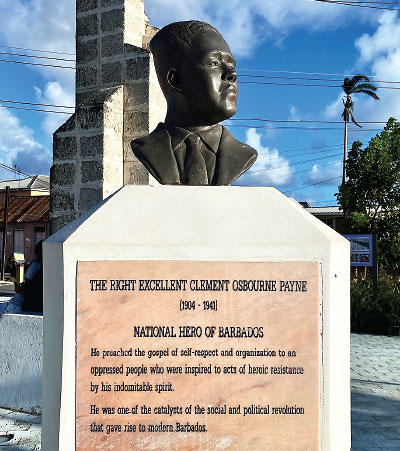

The Freedom Park was established in a working-class area of Bridgetown, where Clement Payne used to conduct mass meetings in the 1930s urging Black Barbadians to resist the White planter class. Clement Osbourne Payne was born in Trinidad to Barbadian parents in 1904. His parents apparently returned to Barbados with their young son around 1908. He progressively earned a reputation in Barbados as a trade unionist and advocate of social justice, especially after spending more time in late-1920s Trinidad sharpening his militancy. He was opposed by the White landowners and ultimately deported from Barbados on July 26, 1937, following the riots provoked by his political agitating. The statue of Clement Payne, shown in the photo, is an important symbol in Freedom Park and is accompanied by another monument nearby. The two make a collective memorial to the individuals who lost their lives or suffered in the struggle for freedom in the 1937 revolt.

The conceptual idea of unsung heroes mentioned earlier was concretized by the creation of the “Builders of Barbados Wall.” It is constructed from bricks on which are inscribed Barbadian surnames. The wall, shown in the photo, celebrates thousands of ordinary people who, although lacking fame or prominence, contributed to the development of Barbados over the past 600 years. Commentators have noted that the monument symbolizes an appreciation of ancestral dignity and illustrates a sense of belonging that everyone hopes can be cultivated in the island’s youth. It is considered an interactive method of bringing history to life.

I did visit this new Golden Square Freedom Park. I stood and looked, walked around, and approached strangers to talk about this new development. Only one man, sitting on a bench absorbed in his private business, gave me a withering look. I left him alone. I watched small groups searching for their names, obviously absorbed in the task of self-recognition with satisfaction on their faces once the discovery was made. I heard regrets and concerns expressed about the park’s proximity to neighborhoods that needed refurbishing. This suggested to observers that the surrounding blight might engulf the park unless maintenance remained a central feature. There was clear understanding of what some have called a gospel of self-respect, enunciated by Clement Payne. There was talk, too, of the new theme of ancestral dignity evident as families searched for their names on the monument’s bricks. Like everybody else, I scrutinized bricks and felt satisfied when I discovered my name in its three Welsh versions: Griffith, Griffiths, and Griffin. It made me think about what my father and grandfather had contributed to the nation building. In any case, they had done more for Barbados than Lord Nelson. ■