“Just the tip of the iceberg” is how child and adolescent psychiatrist Deborah Weisbrot, M.D., characterizes the threat of violence made by a young person at school, sometimes indicative of a wide range of underlying psychiatric disorders.

“Any student who makes a threat, whether it’s minor or severe, needs a thorough assessment by a threat assessment team and a full psychiatric evaluation for what the underlying issues are and to make recommendations for treatment and further educational intervention,” she told Psychiatric News. “Sometimes a student will say of a threat, ‘Oh, it was just a joke.’ But that should not be taken at face value—there may be much more to that joke.”

Weisbrot is a full-time consulting child and adolescent psychiatrist with two therapeutic schools in Suffolk County, N.Y., operated by the New York State Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES); there she works with teachers, school counselors, and community mental health professionals to provide intensive, in-school services for youth with a wide range of psychiatric disorders. The position is supported by Stony Brook University, where she is a clinical professor of psychiatry.

Prior to working with the therapeutic schools, Weisbrot had been director of the child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic at Stony Brook for 16 years. She recalled that it was after the Columbine School shooting in April 1999 that the outpatient clinic began getting many referrals from schools about students who had made some sort of violent threat against others.

“I hadn’t been trained in how to perform a threat assessment, and when I went to the psychiatric literature, there was very little about threat assessment,” Weisbrot said. “I had to teach myself how to do an assessment based on literature from the FBI and the Secret Service.

“We started doing intensive evaluations for these kids, who had very complex psychiatric problems,” she continued. “And what we began to see was that the threat was often a signal for a whole range of other issues—anxiety, family problems, trauma, autism, and sometimes psychosis. Over the years I have been taking note of all of these students’ disturbing stories.”

Now, Weisbrot and colleagues have published a review of the records of children and adolescents referred to the clinic by school staff for threat assessment evaluations between 1998 and 2019 in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. She and her team defined a “threat” as an expression of intent to do harm or act out violently against someone or something. Threats were categorized as being either verbal or nonverbal (such as violent drawings), as well as those that involved bringing a weapon to school.

The study sample included 157 youth aged 5 to 18 years (average age, 13 years); the youth were almost evenly divided between those who were receiving special education services and those who were not. Eighty percent of students had made a verbal threat, and 29.3% had brought a weapon to school. About 50% had a history of psychopharmologic treatment, and 36.3%, psychotherapeutic intervention.

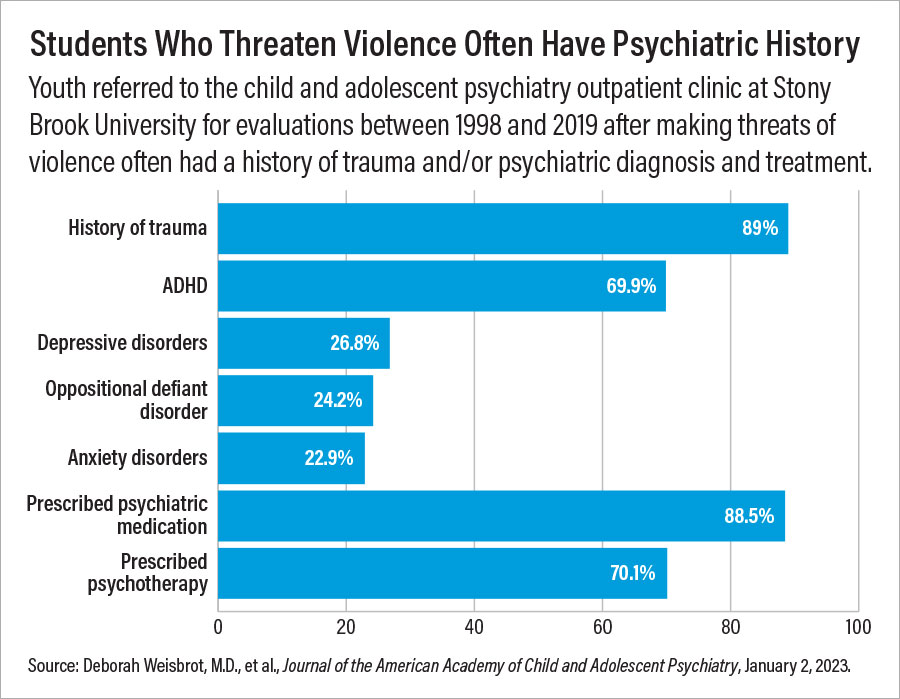

Each student received a psychiatric evaluation with a systematic, semi-structured interview, which also included discussions with the student, school faculty, and the student’s guardian. A history of trauma or psychiatric treatment was common (see chart).

In comments to Psychiatric News, Weisbrot also emphasized the prevalence of suicidality. “In addition to the many students who presented with depressive and anxiety symptoms, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, or self-injury was present in 27 students—17.2%—indicating the need to carefully assess for suicide as well as homicidal ideation.”

In the longer-term history of school shooters, “a striking number were suicidal, as well,” she added.

In her cohort of students, relatively few (about 8%) were regarded as seriously at risk, requiring the police to be notified or a referral for hospitalization or therapeutic schooling. Prior threat history, the presence of paranoid symptoms, and/or the presence of schizotypal symptoms were the factors most likely associated with such a referral.

She pointed out, however, that even in cases in which the student is not deemed to be a high risk, some kind of follow-up intervention is often necessary. And simply removing the student from school is not the answer. “After Columbine, a lot of schools adopted ‘zero tolerance’ policies in which the student would be automatically suspended,” she said. “It was intended to make everyone feel safer, but you are no safer at school if a troubled student is sitting at home isolated. There is more awareness now that zero tolerance is not the way to go.”

Threat assessment requires a team. “Psychiatrists should not assume on their own they can figure this out,” Weisbrot said. “The psychiatrist has to work with the school and there has to be someone to follow the student after the assessment. When a student gets referred to the ER, there may be pressure on the psychiatrist to write ‘safe to go back to school.’ But even if the student is safe to return to school, what else is going to happen? Is it just going to be business as usual, or will there be further intervention?” ■