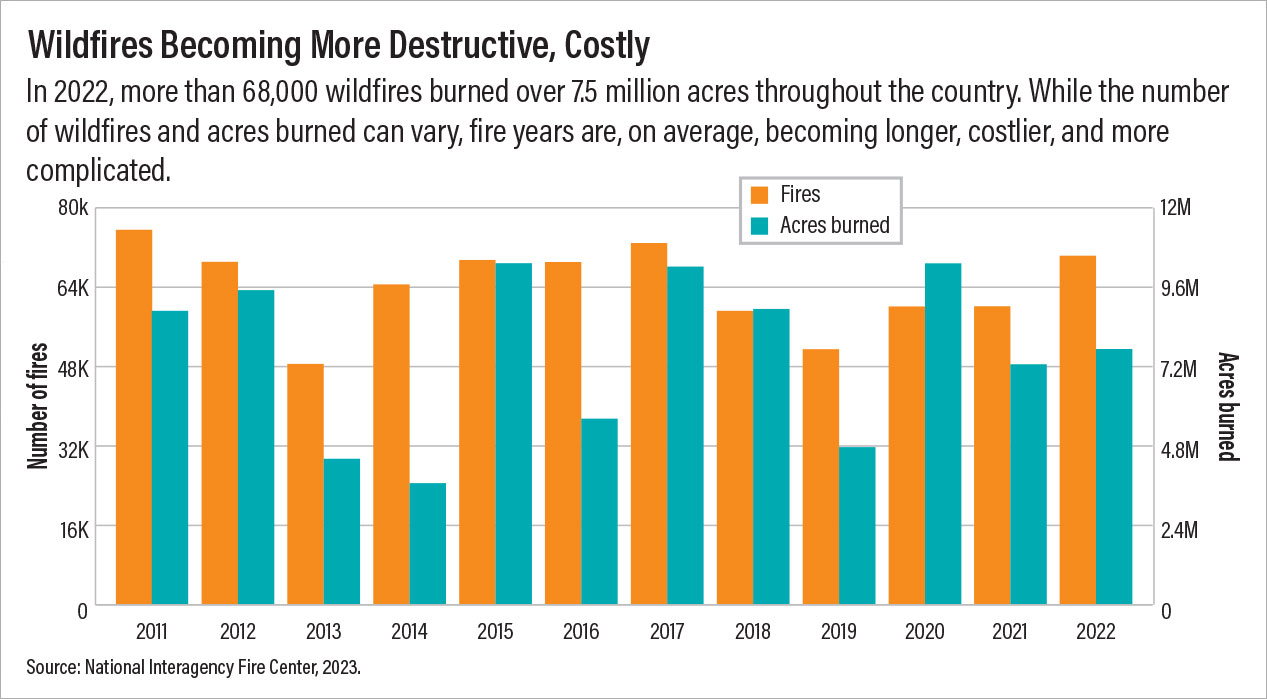

Over the past two decades, wildfires have been increasing in intensity across the United States, spurred on by a changing climate and poor forest management. Today’s forest fires are hotter, longer lasting, and more damaging. For example, the National Centers for Environmental Information estimated that the

damage from wildfires in 2022 was $172 billion. The damage would have been even more catastrophic if not for the teams of wildland firefighters that go out each fire season and protect the public from this force of nature at their own personal risk.

For years, wildfire suppression was viewed as an adventurous form of manual labor. Now, as more and more wildland fires brush up against residential areas, wildland firefighters are finally receiving recognition as first responders entrusted with public safety. However, little is discussed of the individuals in this group, especially the profound physical and mental consequences they experience. But for those of us who have worked under an ash-filled sky or seen loved ones in the profession struggle with psychiatric illness or substance use, the crisis is all too real.

Even if you’ve never crossed paths with one of this country’s roughly 20,000 wildland firefighters, it’s worth understanding more about the hardships they face for comparatively meager compensation and institutional support. Given how much these first responders do to mitigate the mental and physical damage of wildfires on communities across the United States, more professional mental health help should be made available to them.

Wildland Firefighters Face Numerous Stressors

So exactly who are these brave individuals who are willing to tackle a forest fire that may encompass thousands of acres? A wildland fire workforce consists of several specialized roles and includes dispatchers, crews that manage the base camp, and incident management teams who coordinate everything from the suppression operations to catering. The teams that focus on building the fire lines (nonflammable zones around the fire perimeter) are also diverse and make use of handcrews, fire engines, heavy equipment, and aviation resources. Notable among these personnel are the hotshot crews who are typically assigned to complete complex fire suppression operations in terrain that requires a high level of physical fitness and the smokejumpers and helicopter rappelers who deploy from the air to suppress smaller, remote fires that are difficult to access by road or by foot.

The U.S. wildfire season usually lasts about four to six months during the spring and summer (depending on the region), though as noted these seasons have been getting longer. During this time fire crews can take on multiple grueling shifts, often distant from their homes and families. A typical wildland shift involves working 14- to 16-hour days for two straight weeks in the middle of hot, ashy, grimy wilderness. A crew then gets a two- to three-day respite before becoming available for their next assignment, which could be across the country. Even if a particular season might be light on fires, crews keep working; in addition to conducting controlled burns for ecological benefit, wildland crews can also be called in to help with flooding, mudslides, hurricanes, and other environmental disasters. Wildland firefighters were instrumental in bringing order to chaos after the 9/11 attacks in both New York City and Washington D.C.

The risks of injury or death are manifold, with entrapment by fire, smoke inhalation, falling trees, chainsaw mishaps, and vehicle or aviation accidents, to name just a few. Given the rising occurrence of forest fires in inhabited areas, today’s firefighters increasingly face the potential of witnessing human tragedy, including death, and loss when homes and communities burn.

This job stress impacts firefighters’ mental health in multiple ways. In addition to the emotional toll, the rigor of the profession can lead to recurring pain, respiratory issues, and other medical problems—all of which are risk factors for depression and other psychiatric conditions.

Yet physical and emotional difficulties are not constrained to the fire season. After leaving the close-knit community developed with co-workers during the fire season, many firefighters experience isolation and disconnection during their off time. Others struggle to transition back to a family whose lives have continued without them. Though most wildland firefighters are employed full time, seasonal employees may need to find winter work or otherwise face economic hardship. Many turn to drugs and alcohol to cope with this emotional pain, as well as the physical pain brought on by the laborious work.

More Data Needed Regarding Health and Wellness

For years, the mental health impact of these in-season and off-season stressors was not fully appreciated. While there have been many published peer-reviewed studies examining issues such as stress, trauma, burnout, or depression in structural firefighters, such data on wildland firefighters are lacking. There have been a handful of reports looking at psychiatric aftereffects of particularly devastating wildfire incidents (such as occurred in Greece in 2007), but studies on the impact of the profession’s demands on mental health have been lacking.

Although those of us within the wildland firefighter community know the emotional and physical ravages of the job, it is hard to convince those who lead and make policies that there is a problem when there are limited data to back up these claims.

Unfortunately, learning about the problems and needs of wildland firefighters is not as simple as transposing what we know about structural firefighter mental health. As noted above, there are many differences between the groups related to travel, shift time, organizational structure, and the like. There are some structural similarities with military personnel, given the rotating schedule of deployment and leave time, but military personnel have more infrastructure both abroad and at home to assist with mental health needs.

One of the few available comparative studies highlights these differences. A national survey of all types of firefighters conducted several years back found that 55% of firefighters reported a history of suicidal behavior, compared with 32% of non-wildland firefighters, according to a report by Ian H. Stanley et al. in the August 2018 Psychiatry Research. One potential explanation was that wildland firefighters reported less sense of belongingness, such as having few friends and feeling disconnected from other people. However, out of more than 1,100 respondents, only 20 were wildland firefighters, the rest being structural firefighters.

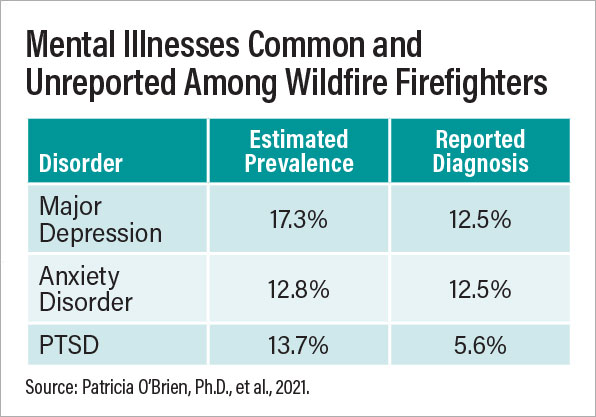

Recently, dedicated researchers (many with ties to the wildland firefighter community) have begun to bring in more quantitative data on a variety of health and wellness topics. Patricia O’Brien, Ph.D., a prior wildland firefighter who went on to pursue a psychology degree, surveyed over 2,600 current, former, and retired wildland firefighters as part of her dissertation. The respondents filled out a variety of mental health screening measures and answered other questions about their experiences. She presented her

findings in 2021 at the Wildfire Sixth Annual Human Dimensions Conference. They were alarming: 17% of wildland firefighters reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of depression, and 13% reported symptoms consistent with generalized anxiety disorder, both about two to three times higher than the general populations. The prevalence of probable posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was nearly 14%, which is four times the rate in the general population. Further, less than half of the respondents who had symptoms consistent with PTSD reported that they had been clinically diagnosed with the disorder, highlighting that this condition remains underdetected, unrecognized and undertreated in a clearly at-risk group. More than half of the respondents reported binge drinking at least once in the past month, while 22% reported heavy drinking. Not surprisingly, cigarette use was rare in this group, but nearly 37% used smokeless tobacco products.

Just last year, another group of firefighters and environmental health researchers released a survey of mental health and job satisfaction among 708 wildland firefighters that offered similar stark results. The findings of the 2022 Wildland Fire Survey suggested relatively low levels of job morale and dissatisfaction with the work-life balance of the profession.

Access to MH Care Stymied by Lack of Insurance, Insufficient Training

Unfortunately, this elevated mental health burden of wildland firefighters is coupled with elevated barriers to reliable mental health care. Accessing counseling services or even getting a prescription refill during the fire season is challenging; given the rural locations of many assignments, even accessing remote care is daunting. Though wildland firefighters have more time in the off-season, annual insurance coverage is provided only to wildland firefighters who are employed full time; married seasonal employees are covered only through spousal plans.

Good health insurance is critical as wildland firefighters are not paid well. Entry-level positions are typically minimum-wage jobs, so the pressures to extend hours for overtime pay and take risk assignments to get “hazard pay” are the only ways for many firefighters to make a livable annual income. In the 2022 Wildland Fire Survey, for instance, 92% of the respondents said they had to work at least 300 overtime hours each season to pay the bills.

But even firefighters who have the motivation and resources to seek help can be stymied by the lack of mental health professionals who understand the culture of their profession and have the training to offer trauma-informed care. While many wildland firefighter employers offer employee assistance programs, reports from those who have used them indicate they are limited in the health benefits they can offer.

As Climate Crisis Worsens, Action Needed Now

We are facing a crisis, and time is of the essence. As climate change is creating the conditions for more frequent, more severe, and longer lasting fires that are occurring in more places, the need for a robust response grows. Additionally, the growth of communities at the wildland-urban interface puts more people at risk to loss of life, property, and community and greater health risks. Just as we face these enormous needs, many firefighter positions are now going unfilled. The combination of a grueling workload with limited support has been taking a toll for years, and the stress and burnout are finally manifesting.

Since wildland firefighters work for a number of different governmental agencies, it is difficult to access the actual attrition rates. However, anecdotal information indicates that over the past three years in California alone, the federal wildland firefighter workforce has shrunk by 20%. Nonetheless, the trend is clear—even as wildfires grow in size and frequency each year, the number of wildland firefighters is decreasing, putting both communities at greater risk and further stressing the mental health of the already stretched workforce.

Fortunately, current and former wildland firefighters have begun to open up and share why they do the job, what it has cost them, and what they want. In addition to all the people who participated in these recent surveys, many others have begun sharing their stories with journalists and news media in the past two years. Daliah Singer, award-winning freelance journalist who was one of the first to tackle writing about this challenging work, has written an exposé on the particular mental health toll of wildland firefighters in

The Guardian and followed up with another article in

Sierra, the magazine of the Sierra Club, with short personal profiles of several wildland firefighters (including one of the authors of this report, Riva Duncan). Their stories reveal simple desires that all of us deserve but few get: more pay, better benefits, a better understanding of the strain the job puts on families, and more accessibility to good mental health care.

In an ideal world, wildland firefighters—current and former—would have access to a health care system similar to that of the Veterans Administration (VA). Given that firefighters travel far distances and across state lines each season, having a national network that provides fee-covered mental health services would be valuable—though the limited free time in-season is still a hurdle.

While a forestry “VA” seems unlikely, there have been a few signs of progress, and much of that can be attributed to the work of nonprofit organizations like the Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, who advocate tirelessly for improved working conditions. In December 2022, the

First Responder Fair RETIRE Act became law; it enables firefighters and other first responders to retain their accelerated retirement benefits even if they become injured and forced to move into a different civil service position. In 2021 the Biden administration passed an order to raise wildland firefighter minimum pay to $15 an hour (still not a livable wage, and firefighters still need to get hazard and overtime pay to make ends meet), though this change may not be permanent. The U.S. House of Representatives has passed the

Wildfire Response and Drought Resiliency Act, which among other provisions codifies the minimum wage of $15 an hour and provides for seven days of mental health leave each season. The bill remains in Senate limbo, so this is an opportunity to contact your Senator to encourage action. There is also a substantial proposal for a permanent pay raise and mental health programs in the president’s fiscal year 2024 budget; however, Congress needs to approve this, which seems unlikely.

How else can psychiatrists and mental health professionals participate in assisting these unsung heroes? Academic-based professionals could explore research studies related to wildland firefighters—we need more data. For example, while we are beginning to appreciate the elevated levels of substance use among firefighters, more details on specific substances such as opioids are sorely needed. Educators should keep raising awareness about the tremendous mental health impact of climate change to our colleagues and the next generation of physicians. And psychiatrists and mental health professionals can look for opportunities to provide high-quality trauma-based care to firefighters and their family members following a major wildfire in the same way that postdisaster counseling is provided to affected civilians. As leaders in this realm, we need to engage our professional organizations to use our professional voice and organizational leverage to join the advocacy efforts of the groups that are bringing the issue to policymakers.

And don’t be shy about sharing any knowledge or concerns about the plight of wildland firefighters with professionals in other disciplines. We need more advocates to call for change, more journalists to open people’s eyes to the problem, and more policymakers willing to introduce legislation. ■