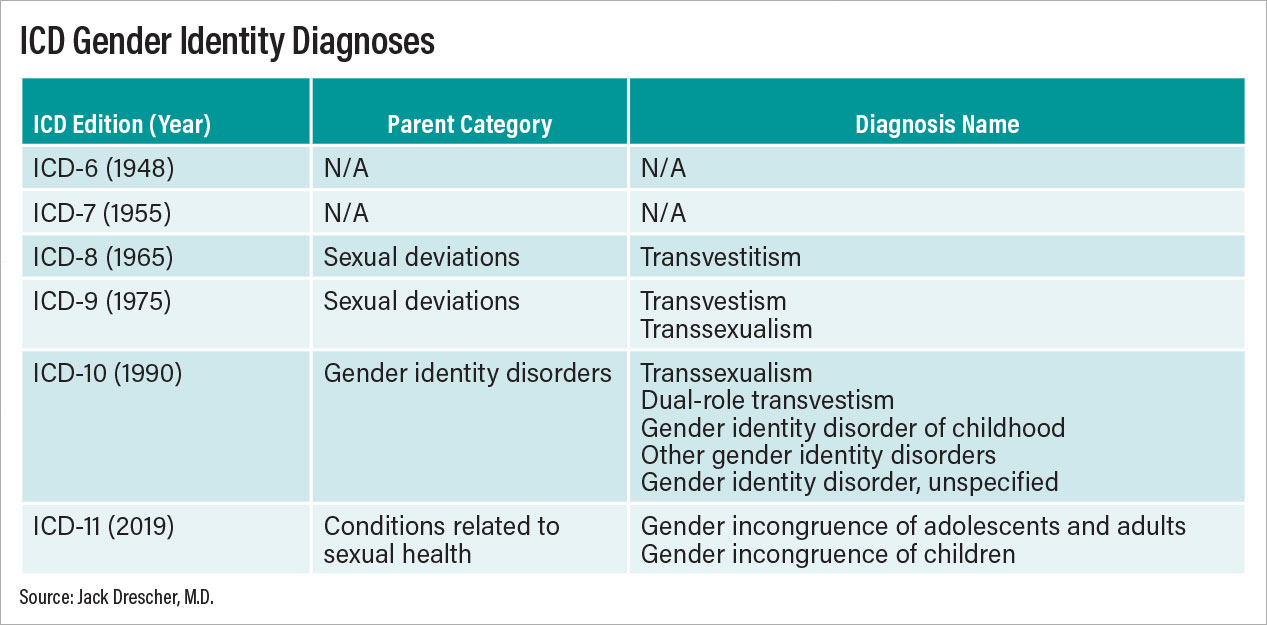

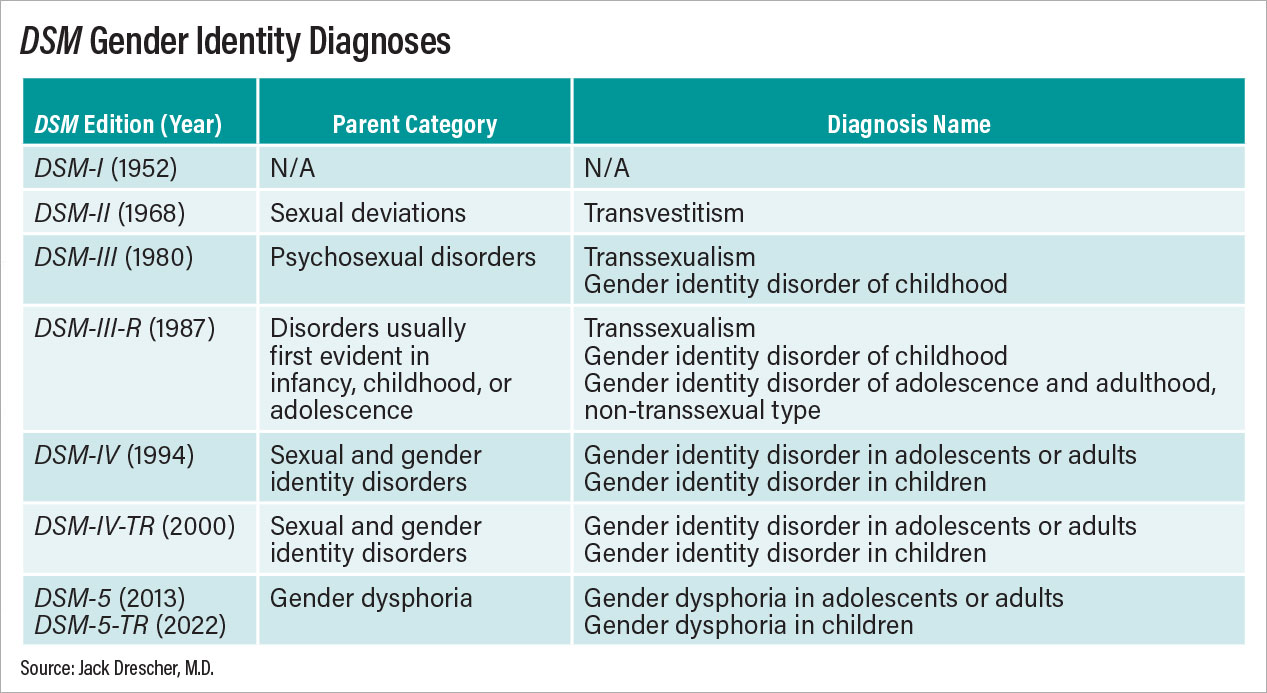

As gender-affirming treatment has become more common in this country, it is not surprising that controversies have arisen around providing such care to youth. To oversimplify, in one corner are those who recognize that such treatment can alleviate mental suffering, improve lives, and sometimes even save lives; and in the opposite corner are those who are opposed to treatment for a variety of reasons, including the unknown long-term effects of hormonal and surgical treatments. What follows are some of my thoughts and opinions about the evolution of these controversies in the treatment of children and adolescents with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (GD) in DSM-5-TR or gender incongruence (GI) in the ICD-11 (World Health Organization).

To begin, I am an adult psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and do not treat children and younger adolescents. However, I first became curious about child treatments during the DSM-5 development process (2007-2013), and together with my colleague William Byne, M.D., Ph.D., began learning about some of the issues raised by these treatments. Little did we know that a relatively obscure, albeit sometimes sensationalized, clinical issue would later lead to major news stories in the popular media, lawsuits against the U.K.’s Tavistock Clinic leading to the 2022 decision to close it, and, in the United States, legislation to prevent transition services for minors in a growing number of states.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1952). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association (1968). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 2nd edition (DSM-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association (1980). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition (DSM-III). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association (1987). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition—Revised (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Benjamin, H. (1966). The Transsexual Phenomenon: A Scientific Report on Transsexualism and Sex Conversion in the Human Male and Female. New York: Julian Press.

Bell, D. (2020). First do no harm. International J Psycho-analysis, 2020, VOL. 101 - NO. 5, 1031-1038.

Byne, W., Bradley, S.J., Coleman, E., Eyler, A.E., Green, R., Menvielle, E.J., Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L., Pleak, R.R. & Tompkins, D.A. (2012). Report of the American Psychiatric Association Task Force on Treatment of Gender Identity Disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(4):759-796.

De Sanctis, V., Soliman, A.T., Di Maio, S., Soliman, N. & Elsedfy, H. (2019). Long-term effects and significant adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs (GnRHa) for central precocious puberty: A brief review of literature. Acta Biomedica, 90(3): 345-359.

de Vries, A.L. & Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. (2012). Clinical management of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents: The Dutch approach. J Homosexuality, 59(3):301-20.

Drescher, J. (2010). Queer diagnoses: Parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39:427–460.

Drescher, J., Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. & Winter, S. (2012). Minding the body: Situating gender diagnoses in the ICD-11. International Review of Psychiatry, 24(6): 568–577.

Drescher, J. & Byne, W., eds. (2013). Treating Transgender Children and Adolescents: An Interdisciplinary Discussion. New York: Routledge.

Drescher, J. & Byne, W. (2014). Controversies in the Treatment of Transgender Children and Adolescents. Scientific Symposium, Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, NY, May 5.

Drescher, J. (2015). Queer diagnoses revisited: the past and future of homosexuality and gender diagnoses in DSM and ICD. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(5):386-395.

Drescher, J. (2016). Gender diagnoses in DSM and ICD. Psychiatric Annals, 46(6):350-354.

Drescher, J., Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. & Reed, G.M. (2016). Gender incongruence of childhood in the ICD-11: Controversies, proposal, and rationale. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(3):297-304.

Drescher, J. (2022a). Is it really about freedom of thought?: A response to Marcus Evans’ “Freedom to Think.” BJPsych Bull, Mar 2, pp. 1-3; doi: 10.1192/bjb.2022.9.

Drescher, J. (2022b). Informed consent or scare tactics? A response to Levine et al.’s “Reconsidering informed consent for trans-identified children, adolescents, and young adults.” J Sex & Marital Therapy, Published Online June 1, DOI: 10.1080/0092623X.2022.2080780.

Drescher, J. & Byne, W. (in press). Gender identity, gender variance and gender dysphoria/incongruence. In: Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 11th Edition, eds. R. Boland & M. Verduin. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Ehrensaft, D. (2012). From gender identity disorder to gender identity creativity: True gender self child therapy. J Homosexuality, 59(3):337-356.

Eugster, E.A. (2019). Treatment of central precocious puberty. Journal of the Endocrine Society, 3(5):965-972.

Evans, M. (2021). Freedom to think: The need for thorough assessment and treatment of gender dysphoric children. British J Psychiatry Bulletin, 45(5):285-290.

Green, R. (1987). The “Sissy Boy Syndrome” and the Development of Homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hamburger, C., Stürup, G. K. & Dahl-Iversen, E. (1953). Transvestism: Hormonal, psychiatric, and surgical treatment. JAMA, 12(6):391-396.

Hirschfeld, M. (1923). Die intersexuelle Konstitution. Jahrbuch fur Sexuelle Zwischenstufen, 23:3-27.

Jorgensen, C. (1967). Christine Jorgensen: A Personal Autobiography. New York: Paul S. Ericksson, Inc.

Krafft-Ebing, R. (1886). Psychopathia Sexualis, trans. H. Wedeck. New York: Putnam, 1965.

Schwartz, D. (2021). Clinical and ethical considerations in the treatment of gender dysphoric children and adolescents: When doing less is helping more. J Infant, Child, & Adolescent Psychotherapy, 20(4)):439-449.

Steensma, T.D. & Cohen-Kettenis, P.T. (2018). A critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistence” theories about transgender and gender non-conforming children. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1):225-230.

Sultan, C., Gaspari, L., Maimoun, L., Kalfa, N. & Paris, F. (2018). Disorders of puberty. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 48:62-89.

Temple Newhook, J., Pyne, J., Winters, K., Feder, S., Holmes, C., Tosh, J., Sinnott, M.L., Jamieson, A. & Pickett, S. (2018). A critical commentary on follow-up studies and “desistance” theories about transgender and gender-nonconforming children. International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1): 212-224.

World Health Organization (1975). International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th Revision (ICD-9). Geneva, Switzerland.

World Health Organization (1992). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Geneva.

World Health Organization (2019). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision (ICD-11). Geneva.

Zucker, K.J. & Spitzer, R.L (2005). Was the Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood diagnosis introduced into DSM-III as a backdoor maneuver to replace homosexuality? A historical note. J. Sex & Marital Therapy, 31:31-42.

Zucker, K.J., Wood, H., Singh, D. & Bradley, S.J. (2012). A developmental, biopsychosocial model for the treatment of children with gender identity disorder. J Homosexuality, 59(3):369-397.

Zucker, K.J. (2018). The myth of persistence: Response to “A critical commentary on follow-up studies and ‘desistance’ theories about transgender and gender non-conforming children” by Temple Newhook et al., International Journal of Transgenderism, 19(1):231-245.