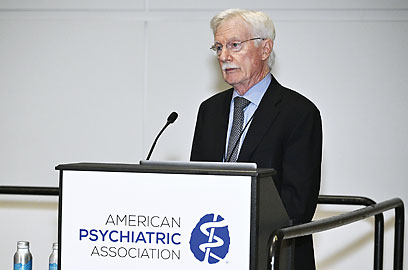

For decades, alcohol use disorder (AUD) has been the proverbial “elephant in the room” when it came to discussing addiction, said National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Director George Koob, Ph.D., during a presentation at APA’s Annual Meeting in May. It shows just how ingrained alcohol has become in the American social fabric when a disorder that affects about 30 million people and is involved in about 140,000 deaths each year remains overlooked, he continued.

But on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, “we might be at the beginning of a sea change in the United States regarding our perceptions of alcohol,” Koob told the audience. “People are beginning to see the scope of the problem.”

Since the start of the pandemic in 2020, hospitalizations for hepatitis, the prevalence of alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients, and alcohol-related driving fatalities have risen, he continued. Notably, 2020 saw a 25% increase in the number of death certificates that listed alcohol as a primary cause compared with the previous year. The number of alcohol-related deaths has fallen slightly in more recent years, but Koob said if previous events such as Hurricane Katrina or 9/11 are any indication, alcohol-related deaths will not return to pre-pandemic levels anytime soon.

However, one silver lining of the pandemic may be that COVID-19 exposed the “dark side of drinking”—the concept that negative emotional states can drive alcohol use. As people were dealing with isolation, school closures, financial problems, and more that arose during the pandemic, they turned to alcohol not as a social lubricant or a celebratory treat, but as a coping mechanism. Though it offered temporary relief, many individuals also experienced adverse consequences of drinking and embraced a change.

For example, motivational challenges such as “Dry January” have gained real momentum, Koob said. “It has been heartening to see how much the idea has really caught on, especially this year,” said Koob. “I almost went hoarse this past January with all the interview requests I had.” Likewise, the rising availability of mocktails and even full dry bars have enabled people to have the experience of social drinking while avoiding the consequences of alcohol use.

Koob called for physicians to capitalize on this momentum for change. “We need to integrate more AUD care into routine clinical practice,” he said.

According to data presented by Koob, 70% of people with AUD symptoms said they were screened by a physician, but only 11% were given a brief behavioral intervention, and just 6% were referred to a treatment program.

Koob said that NIAAA has launched an initiative with hepatologists to integrate AUD care into liver disease care to improve patient outcomes and hopefully reduce the demand for liver transplants. Koob suggested that psychiatrists adopt a similar approach and make SBIRT (screen, briefly intervene, refer, and treat) part of routine patient care.

He noted that

NIAAA’s Core Resource on Alcohol has information on reliable screening tools, details on FDA-approved medications for AUD, how to give a brief behavioral intervention, and more. ■