Mood disorders have been described since ancient times, and for most of this history, treatment was limited to supportive care, herbal remedies, or dubious medical interventions. Following World War II, however, the serendipitous discoveries of the mood-restoring properties of imipramine, chlorpromazine, and lithium (the first generation of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers) finally gave physicians reliable interventions to manage mood disorders from a mechanistic standpoint. Nonpharmacological, evidence-based cognitive and behavioral therapies also emerged during this time, as did safer protocols for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), providing two more avenues of treatment.

While advances in pharmacology, psychotherapy, and neuromodulation continued over the next decades, acute and chronic management of mood disorders remained to a large extent “trial-and-error” that did not meet the therapeutic needs of many patients. From this frustration came the appreciation that while monoamine theory was an important aspect of mood disorder pathophysiology, it was but one part of a bigger story. The complexity of these disorders arose from a multitude of genetic, developmental, hormonal, social, and environmental factors that evolve and change across the lifespan.

Advances in scientific discovery will aid further development of new generations of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions for mood disorders. Furthermore, diagnosis and management of mood disorders requires integration of the existing evidence-based treatments with new, multidisciplinary team approaches ensuring continuity of care.

The APA Publishing Textbook of Mood Disorders, Second Edition, provides a comprehensive overview of the current evidence underlying treatment for all mood disorder subtypes as well as treatment of special populations such as youth, the elderly, sex-specific presentations, and those with multiple psychiatric and medical comorbidities; it also considers some new advances in the field as it evolves, some of which are described below.

Emphasizing Integrated, Rational Care

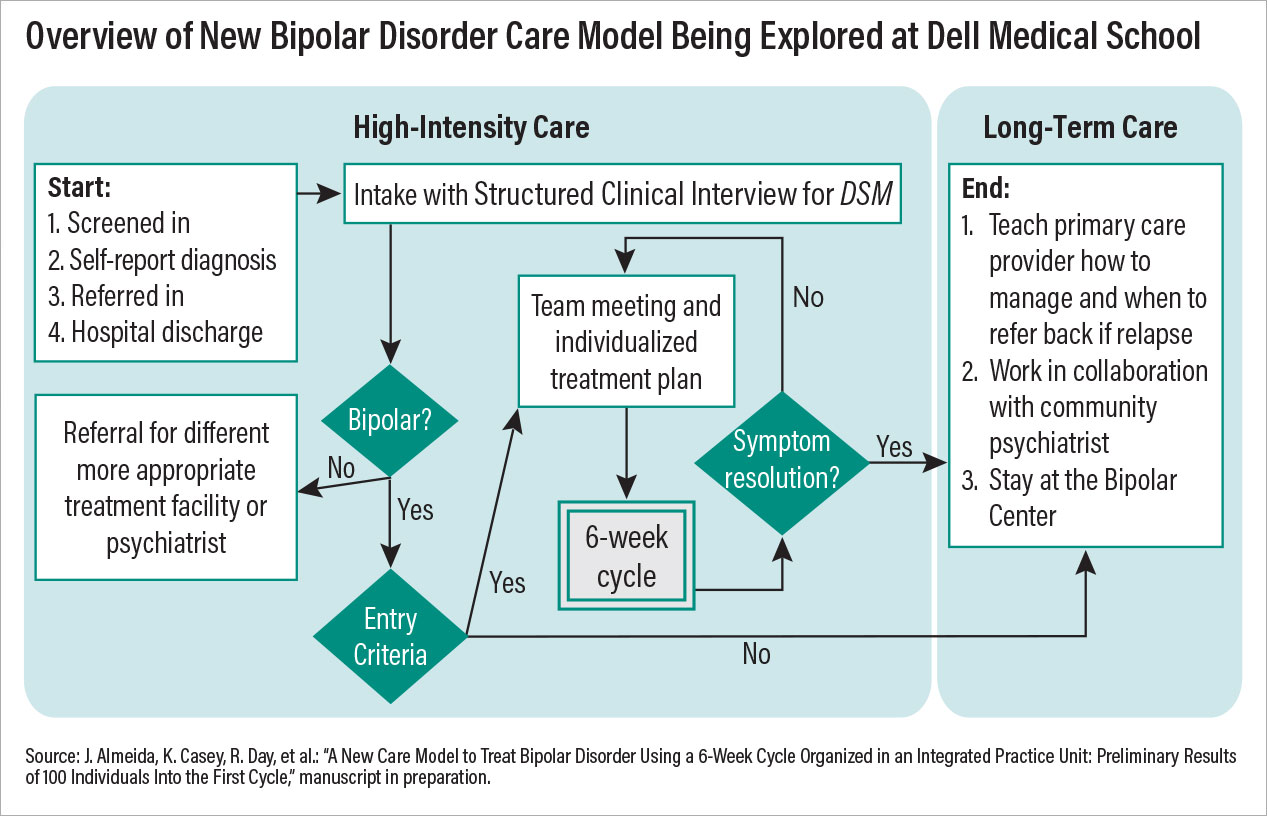

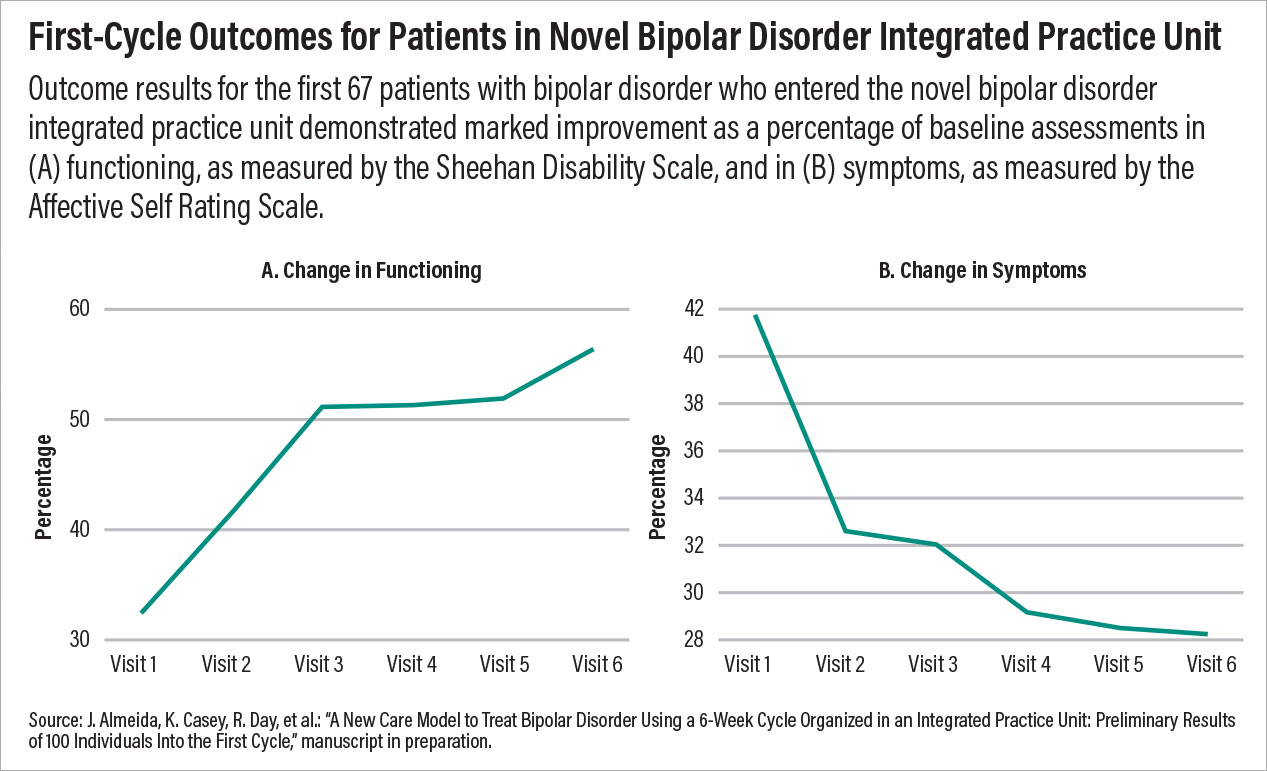

One good example of re-imagining care is occurring at the Bipolar Disorder Center at the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School. The center operates as an integrated practice unit, where a multidisciplinary team (psychiatrist, psychotherapist, pharmacist, peer support specialist, and more) offers coordinated services within a six-week “cycle of care.” The use of this cycle is a deliberate effort to establish a period of treatment that is measurable and repeatable.

Potential Bipolar Disorder Center patients are given a thorough, structured diagnostic evaluation before starting a cycle to ensure the underlying issue is bipolar disorder and not another mood problem. At the start of a cycle, the clinical team establishes a personalized treatment plan focused on six of the most problematic areas (out of a list of 24 common bipolar-related issues) identified by the patient. The team then provides evidence-based care (medications and psychosocial interventions) for these core issues while meeting with the patient each week; at each visit, patients compose their own outcome reports to relay their perspective on care, which is used by the clinical staff to modify the care plan.

If problems do not resolve after six weeks, then the clinical team meets again to discuss possible reasons for nonresponse and begins another cycle. Patients who do respond can continue at the bipolar center to manage further symptoms or transfer out to community care.

This model being tested at the Dell Medical School incorporates some of the most important facets of psychiatric care that are known to improve outcomes. First, it includes a collaborative team of diverse experts focused on a specific disorder; second, it provides measurement-based care with predetermined goals and a set period of time. Third, the model is patient centered, with each patient taking an active role in his or her care, from assessment to discharge. Preliminary outcomes data suggest that the symptoms and functioning of many patients improve within just one treatment cycle, and after the data are published, clinicians across the country should review and consider incorporating similar models of care at their centers.

Moving Beyond Monoamines

Pharmacologic progress in mood disorder treatment has been an uneven journey composed of peaks and valleys since the discovery of the first tricyclic antidepressants. The current trajectory is very promising, and it started in March 2019 with the arrival of not one but two novel depression medications. First was the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of esketamine (Spravato), a nasal spray that could be used alongside conventional antidepressants to manage treatment-resistant depression. Two weeks later, the agency approved brexanolone (Zulresso), a neurosteroid that was administered intravenously to treat postpartum depression in women. The two medications had differing molecular targets, with esketamine targeting NMDA receptors and brexanolone targeting GABA receptors, but both offered rapid symptom relief. Improvements could be seen within 24 hours, and a full response or even remission was possible within a few days.

There are certain limitations to both medications. Neither is an at-home medication like a conventional antidepressant; esketamine must be given under supervision in a clinical setting due to dissociative side effects and concerns about misuse, while brexanolone infusions require 60 hours and thus a three-day hospital stay. But for some individuals experiencing severe and acute depression symptoms, these new options could be lifesaving.

Beyond immediate clinical applications, the approval of esketamine and brexanolone showed there was pharmacologic potential outside of serotonin and other monoamines. A new era of drug development has emerged with the goal of discovering fast-acting and long-lasting agents. The year 2022 saw the approval of an extended-release dextromethorphan+bupropion combination (Auvelity) that some have considered ketamine in pill form. There are still limited data on the long-term effects and safety of this medication, and the available clinical data suggest that Auvelity is less effective in people with treatment-resistant depression—where it seems suited clinically.

Just a few months back, an additional medication option became available for women experiencing postpartum depression. Zuranolone (Zurzuvae), a synthetic neurosteroid similar to brexanolone, generated excitement as it was one of the few psychotropic medications that does not require continual use; rather, it is a 10-day oral pill regimen. The excitement of zuranolone was tempered as the drug did not receive concurrent approval for major depression, which would open the possibility of “as-needed” symptom care to tens of millions of Americans.

Many more promising drugs are in the pipeline, and these include psychedelic compounds like psilocybin and MDMA; both medications were recently legalized for treatment in Australia and have FDA breakthrough designations in the United States. With research suggesting that these compounds and ketamine can promote neuroplasticity, there is hope of another shift in therapy, where medications may help rewire the brain to a healthier state as opposed to offering transient improvements.

TMS Gets Personal

The first transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device was approved for treatment-resistant depression in 2008, and in the ensuing 15 years, this treatment modality has advanced and expanded dramatically. New devices (including a portable TMS for migraine), new modalities (deep TMS that reaches several centimeters beneath the skull, theta burst stimulation that delivers therapeutic stimulation in just three minutes), and new indications (obsessive-compulsive disorder) have all emerged in recent years. Yet TMS still faces the same limitations as other mood disorder treatments; the therapy offers a solid but far from perfect 50% response rate and requires repeated maintenance sessions to maintain symptom improvements.

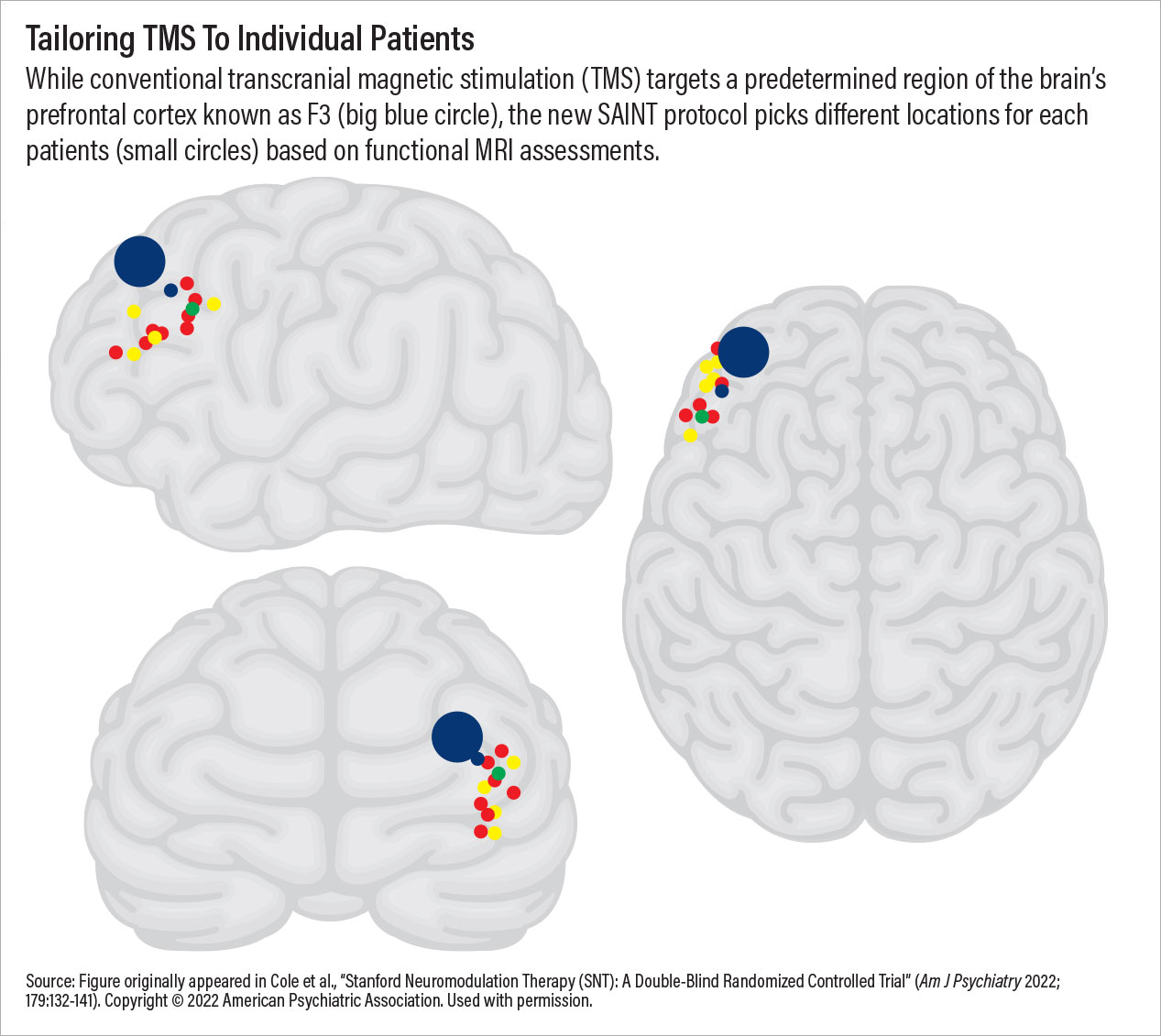

TMS therapy may have achieved a critical breakthrough in September 2022 with the approval of the

SAINT Neuromodulation System, which was developed at Stanford University. This TMS procedure makes use of the aforementioned theta burst stimulation protocol along with established concepts in learning theory to provide 10 treatment sessions in a single day at optimally spaced intervals. The standard SAINT protocol involves five consecutive days of treatment, though data indicate that many individuals—especially people with no prior TMS exposure—show significant mood improvements after just one day. This truncated schedule will benefit many outpatients but could also be transformative for inpatient care in the United States, where the average stay for a depressive disorder is about six days.

Additionally, SAINT provides impressive response rates (80% to 90% in clinical trials though real-world outcomes will be lower). This is because every SAINT recipient receives a resting-state MRI scan prior to the first session; the MRI pinpoints the area within the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex that would most likely respond to the magnetic stimulation. SAINT may be considered one of the first personalized depression treatments available, and it was made possible by combining new ideas with old and bringing together advances in neuroscience, radiology, and engineering.

The Promise of Precision Care?

The next clinical frontier in mood disorders will be achieving precision patient care. A generation ago, many believed genetic testing might offer that precision, but mood disorders are complex and dynamic illnesses with genetic, epigenetic, and environmental etiologies.

It is apparent that the proper path toward precision medicine for the treatment of mood disorders must synthesize information from multiple contributing factors to disease formation—genetic, environmental, psychosocial, and neurobiological. Such effort requires use of machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence that allow for deep phenotyping of patient data culled from electronic health records, biobanks, and other sources. While we are only at the beginning of the integration of complex modeling into framework of mood disorders studies, it is inspiring and hopeful that large data will someday provide better diagnostic and treatment algorithms for individual patients and help clinicians change the paradigm of mood disorders care from “trial and error” to “trial and success.” ■