Last year, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy released an

advisory report to call attention to a major public health problem apparent to many of us in the psychiatric community for years: the negative impact of social media on youth mental health.

While acknowledging that social media offers positive benefits to youth, the advisory warned that these platforms expose children to inappropriate or harmful content and can exacerbate negative feelings related to self-esteem, body image, and social standing.

Further, social media itself can be detrimental, as emerging evidence is showing that excess or unhealthy use of the platforms can alter brain physiology in a manner that bears some resemblance to the changes observed with substance use disorders. The dopamine rush that occurs as someone racks up likes on a tweet can potentially be addictive.

Two decades ago, the fascination with Blackberry mobile devices among many business professionals led to the rise of the “Crackberry” meme. As digital communication continues to become even more embedded in everyday life, the language of addiction is no longer employed lightheartedly; social media addiction—or more broadly pathological social media use—is a serious and pressing problem, especially among our youth.

When Is the Line Crossed?

Social media addiction is a concept that seems intuitive but can be difficult to define. Most people can probably name the big social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok, but may be less clear on what criteria define these programs as a collective.

One common definition is that social media are websites and/or apps that promote networking with others via the sharing of content; that content can encompass almost anything that can be shared digitally such as photos, videos, songs, recipes, opinions, comments, personal messages, and so on. What determines whether usage is pathological is how that content is consumed. When does the consumption of social media cross a line to be considered addictive? This too can be difficult to define as there is no recognized set of diagnostic criteria. As of

DSM-5-TR (2022), gambling disorder is the only behavioral addiction diagnosis included in the manual. (Internet gaming disorder is listed in “

Conditions for Further Study,” and some provisional criteria are noted.)

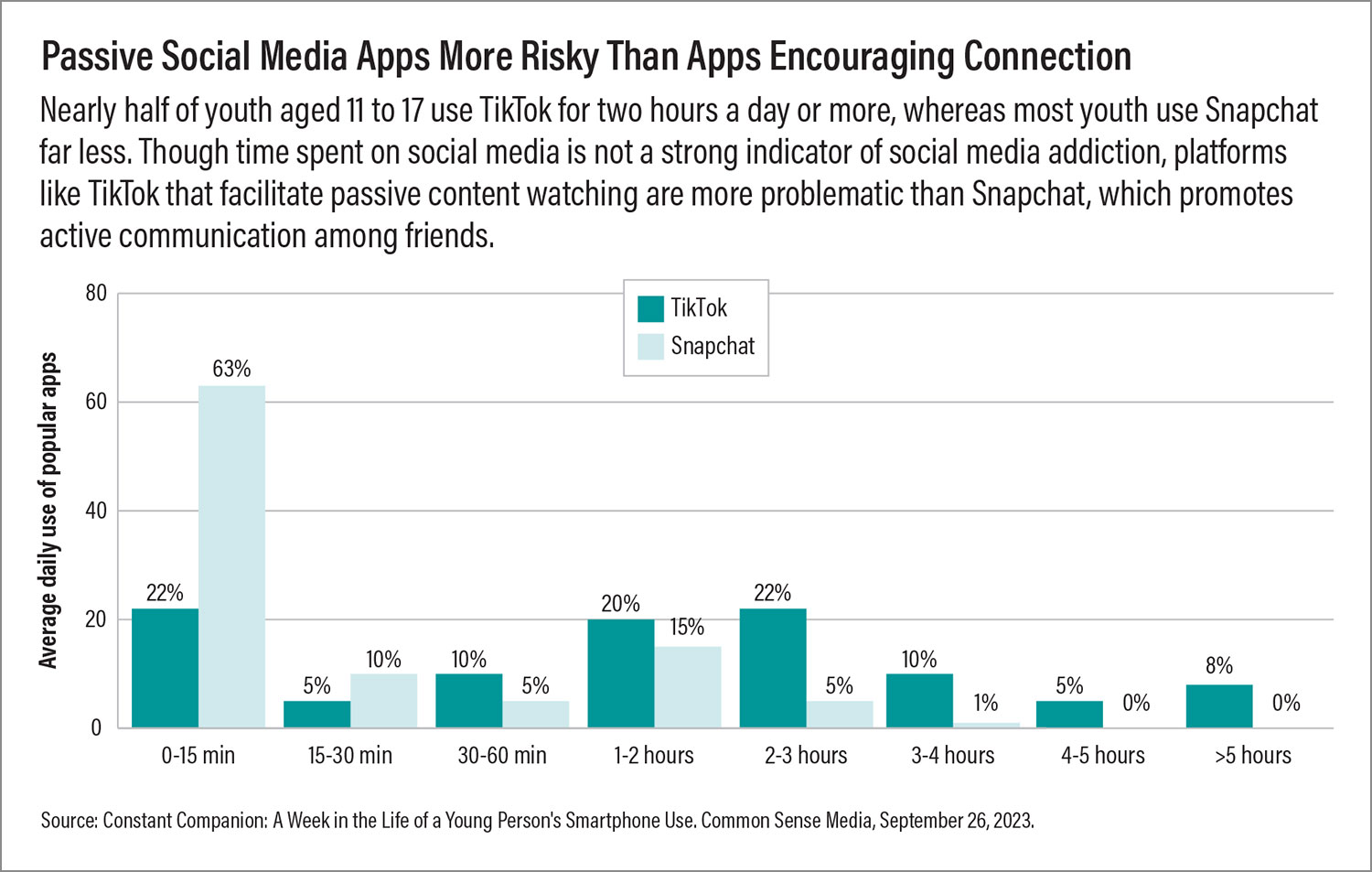

By itself, time spent on social media does not tightly correlate with the risk of addiction. Someone can spend eight hours on social media on a slow weekend day without much issue. Excess social media use during school hours isn’t ideal, but it may not be a problem if academics or socializing don’t suffer. Rather, the engagement level of the user is more relevant; mindless link jumping or passive scrolling are riskier behaviors than actively posting or sharing photos.

Many individuals may have a serious social media habit, but only a small subset reach the threshold of having a clinically debilitating disorder. True pathological use requires that the desire to be on social media impairs functioning to the point that multiple aspects of daily life—school, friends, diet, sleep—are affected. Our goal as mental health professionals is to identify and manage social media addiction before the consequences become too severe.

Suggested Screening Tools

Though there are no official diagnostic criteria to guide us, researchers have developed and validated several tools that can screen young people for problematic social media use. Some popular ones include the following:

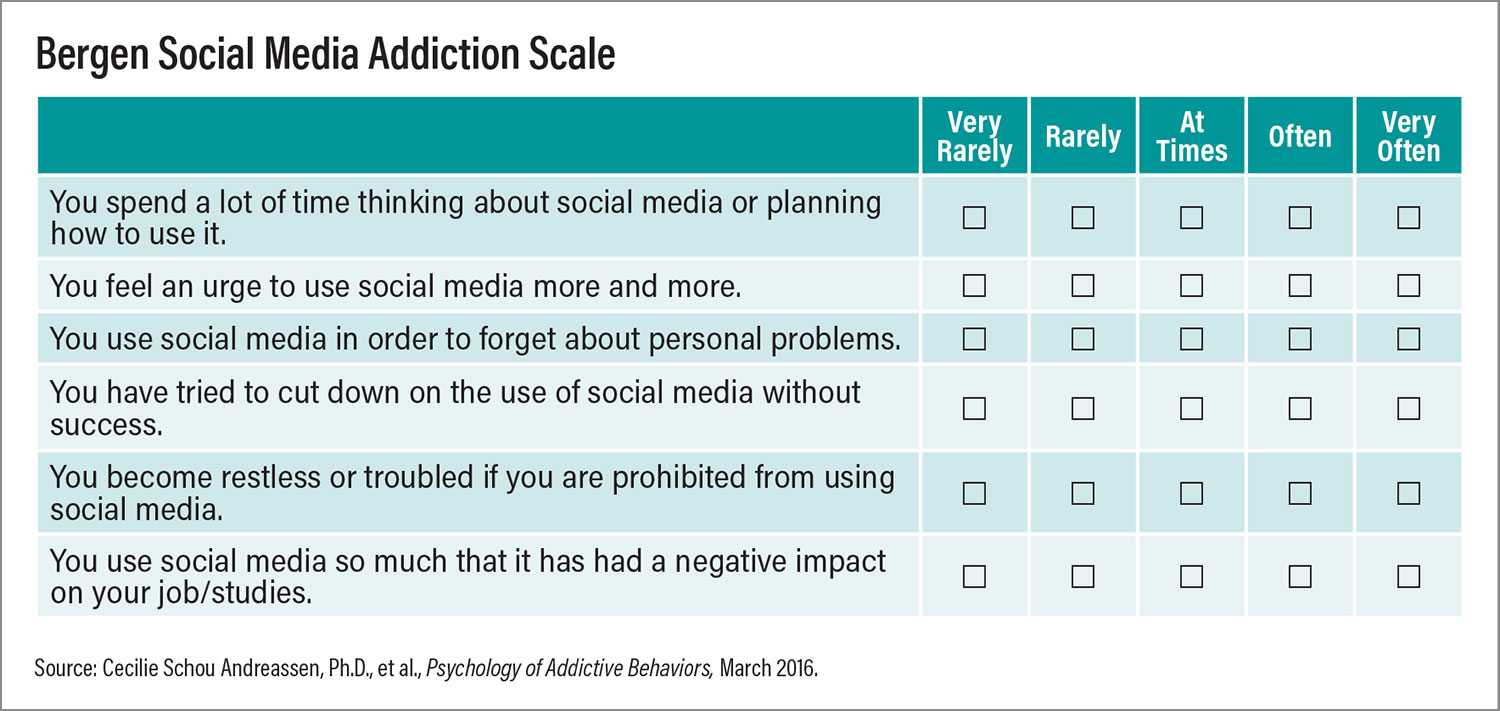

•

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale: This tool, originally developed as the

Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale, consists of six statements, each related to a core domain of addiction: preoccupation, mood modification, conflict, tolerance, withdrawal, and relapse. Patients respond to each statement on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with a score of 24 or above generally considered a warning of potential addiction. Straightforward and quick to administer, this is an ideal tool for children and adolescents.

•

Social Media Disorder Scale: This measure includes

nine yes/no questions, each based on one of

DSM-5’s proposed criteria for internet gaming disorder. These include symptoms related to the six addiction domains as well as consequences like family problems or job loss. A positive answer to five of the nine questions signals a potential disorder.

•

Social Media Addiction Scale: This scale is a more comprehensive

41-item Likert-based assessment that focuses on four of the six addiction domains (it has no tolerance or withdrawal queries). Though time consuming, this test can provide greater insight into severity as there are score cutoffs for mild, moderate, and severe social media addiction.

The rapid evolution of social media apps will likely necessitate that these screening tools are updated and revised regularly. Whatever the method of assessment, any potential signs of social media addiction should be followed with a structured interview to confirm the problem and understand what is driving the behavior.

As with other behavioral use disorders, there are multiple routes by which social media use can convert from habit to addiction, and these can inform treatment.

•

The cognitive-behavioral route: Here, excessive social networking is the consequence of users with maladaptive thinking (perhaps due to other conditions like major depression) who see social media as a means of relief or gratification.

•

The social skill route: This is commonly initiated by people who gravitate to social media due to problems with self-esteem or self-presentation that impacts their real-world interactions. These same problems with the “self” make such users more vulnerable to social media overuse.

•

The socio-cognitive route: Addiction is initiated by the continued social media use of someone with inflated self-efficacy toward social media (he/she believes it can help with any problem) coupled with reduced self-regulation to use social media in moderation.

Clinicians should also be on the lookout for pathological, nonaddictive social media use. This occurs when social media behavior may not meet a screening cutoff, but online behavior is clearly driving the development of internal (for example, loneliness) or external (for example, cyberbullying) problems.

A good starting point for an interview is to ask patients which sites they use and the time allocated during the day, night, and weekends. One might then follow up by asking patients how they use their social media time:

•

Are they actively posting content or are they passively scrolling?

•

Are their accounts named or anonymous?

•

Does their online persona reflect their offline selves or is there a mismatch?

It is also useful to ask about patients’ specific goals with their usage. For example, if an individual is continually scrolling through exercise or fad diet videos, it’s possible the problematic social media use is an attempt to cope with body dysmorphia. If a patient is always browsing due to FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out), then the problem may reside in anxiety or self-esteem issues.

While a clinical interview is designed to understand the causes and harms of social media addiction, psychiatrists should also ask patients about any positive aspects of their social media use to get the full picture. As clinicians, we tend to focus on the negative side of behavior, but social media can be a positive force. Many LGBTQ youth across the globe are growing up in homophobic environments and use social media to find friendship, solace, validation, and more. Given their adverse life experience, they are vulnerable to developing a social media addiction, but this creates a scenario where their interactions are both causing some problems and solving others.

Since treatment for social media addiction typically involves regulation of social media access, appreciating the full risk-benefit profile of each patient can optimize this regulation.

Setting Treatment Goals

As commonly understood, social media has been around for only two and a half decades, and our clinical management of social media addiction is very much a work in progress. While best practices for more established addictions including gambling disorder may offer some guidance, some tenets of substance use disorder care, such as encouraging abstinence, are not feasible with social media use. Rather, we seek to promote healthy social media use while managing potential underlying causes of misuse.

What is healthy use? There is no magic standard of having someone limit their use to X hours a day on no more than Y number of platforms. Rather, the goal is to have patients be able to use social media in a way they can self-regulate. Child and adolescent patients will inherently struggle more with self-regulation, given that a certain amount of executive function is age dependent.

Self-regulation by youth who are misusing social media will take time, as children and adolescents are still developing their impulse control mechanisms. A practical approach is to start with external regulation enforced by parents and/or others in guiding roles such as coaches or counselors. The regulation typically involves some form of contingency management, such as a social media contract. Set amounts of social media time are granted when conditions are met; for example, after all homework is completed. All use should also be stated with a purpose—“I want to connect with some friends”—to minimize passive browsing.

While empowering patients to regain control of their social media habit, clinicians should aim to address underlying and/or comorbid problems that contribute to the addictive behavior. Though there is no “gold standard” approach, cognitive-behavioral therapy can be appropriate for many patients, particularly when a cognitive dysfunction like maladaptive thinking may be a root cause. Psychodynamic psychotherapy—in which therapists help patients communicate their inner feelings—can also be useful as many people who misuse social media struggle with different personas.

Adjunct medications may be useful, but the evidence is thin. Emerging data suggest that bupropion might be effective for internet gaming disorder, which many professionals see as a close cousin to social media disorder, given the social aspects of today’s online games. Pharmacology for addictive behavior should be considered a short-term option, although maintenance medications can be useful in managing co-occurring psychiatric disorders like depression.

Finally, we should not forget the value of lifestyle interventions. Encouraging youth with social media problems to take up hobbies such as sports, hiking, reading books, or journaling can help keep idle hands busy and readjust brains to appreciate non-instant gratification. Let’s turn that FOMO into JOMO (the joy of missing out).

What Can Parents Do?

Unfortunately, our clinical time with patients is limited; parents are on the frontlines of keeping their children with a social media problem on the right path. While we can help develop a contingency management plan, parents need to monitor their child’s social media use and other areas of concern (for example, schoolwork) to make sure the plan is followed.

There are steps parents can take to keep the home environment a healthy space. As part of a social media hygiene plan, they should designate certain activities or zones as tech-free; for example, no social media at dinner, when driving, and before bed. These should be shared ideas that parents commit to as well as good role models.

While keeping youth busy with nondigital activities is encouraged, parents can also guide their kids toward more productive digital hobbies; perhaps someone who posts incessant TikTok videos can be tasked with making a longer-form video project. This way the child can develop valuable audio and visual skills while remaining close to a technology that is found enjoyable.

All this effort may seem daunting, but if available, family-based therapies are an option. These psychoeducational sessions can help parents set and enforce limits while fostering the child’s autonomy.

Appreciating the Scope of the Problem

Beyond helping our patients control problematic social media use, psychiatrists need to be part of the discussion about addressing this problem on a broader scale, for the scale seems to be tilting in the wrong direction.

One

recent analysis that used the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale as a guide suggested a global social media addiction prevalence of 5% using a strict cutoff (total score of at least 24 and a score of at least 4 on each of the six questions). Using just a total score of 24+ raised the prevalence to 8%, while using a score of 18+ raised the prevalence up to 25%. The pool of people who may be on the cusp of an illness could be tremendous.

Based on what we have seen in my clinical practice, these prevalence numbers are not surprising, and they also mirror the realities that parents and teachers are reporting to me.

Some other data specific to today’s youth are also striking if, again, not surprising:

•

The average teen is on social media over three hours a day, and over one-third of teenage girls reported “feeling addicted” to their social media accounts, according to the surgeon general’s advisory.

•

51% of teens admit they are on social media too much, and more than three-quarters of these teens say it would be hard to give up social media, according to a 2022 survey from Pew Research.

•

In 2021, nearly 40% of tweens (ages 8 to 12) reported using social media at least once, and 18% said they used it every day. Many of these tweens were logging on to social media apps that are rated for teens or older, according to

Common Sense media.

As noted, just spending “too much time” on social media may not be a danger. Still, the prolonged and largely unfettered use of social media among tweens and teens is concerning from a health standpoint. The adolescent years are a critical period of brain and body development. Adolescence is also a period of high susceptibility to external pressures, such as those that can be found in social media feeds. Unhealthy social media use can adversely impact brain development and has been associated with risks of depression, sleep problems, disordered eating, and even attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Our clinical experience has also shown that the younger someone develops a problem, the more likely it becomes a persistent and severe problem. Identifying and managing problematic social media use in youth is thus an important component of pediatric mental health care.

Need for Policy Setting

One clear goal in our field is to ensure continued, high-quality research on the etiology, presentation, and treatment of social media addiction and related technological use disorders; we need to continue to build the evidence base that will support the inclusion of these disorders in DSM and ICD.

Those of us who work in addiction psychiatry should also educate our colleagues in other areas of medicine, especially those who regularly see pediatric patients, about the nuances that distinguish general social media excess with social media addiction. Potential problems need to be identified early, but with psychiatrists and psychotherapists already in short supply, we need to save our resources for those who really need them. We should also strive to educate the public when opportunities arise; it’s actually a golden opportunity in that we can easily reach people affected by pathological social media use where they are—on these platforms. Many younger psychiatrists are becoming savvy social media influencers and could be a key asset.

In the long run, though, it is vital that we develop measures that can limit the potential harm that social media can bring to youth. In recent years, we’ve heard several tech CEOs state that they don’t let their children use social media—that should say something about the risks these sites pose.

On the plus side, the people with policy power have started to take notice. In 2023, 35 states and Puerto Rico

introduced legislation related to social media use by children; 12 states successfully adopted measures, which ranged from establishing task forces to incorporating more digital literacy in school curricula to requiring companies to verify the age of all state residents. There are significant logistical challenges in enforcing a social media ban, and it’s possible banning these sites will add to their allure and encourage youth to use them more. We believe social media should be available but regulated.

There are steps that parents can take now to protect their children, but time limits and other parental controls set on devices can do only so much. We need these platforms to put more safety and privacy measures in place, either via encouragement or enforcement. In this country, TikTok has an “under 13” mode that limits certain features and advertising, which is a good first step. However, this feature doesn’t address that adolescents are also at risk for social media harms.

Logging Off

It’s amazing to think that social media is still in its infancy, given that it has become engrained in our social fabric, especially among today’s youth, who were born in an online world. As these tools are increasingly becoming mainstays in how we live, work, and play, the potential for abuse will only grow. However, our society has made significant progress in addressing other addictions that were accepted norms, as evidenced by dramatic declines in smoking over the past few decades. If psychiatrists and other mental health professionals get motivated, we can prevent social media addiction from getting out of hand. ■