When Ethan Sacks’s daughter, Naomi Sacks, was hospitalized with severe depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, he would spend a lot of time sitting in the hospital’s cafeteria, waiting for visiting hours to start so he could see her.

“It was a very rough time, and we didn’t know as much as we do now about the mental health journeys people go on,” he said. “I was dealing with all the guilt and nervousness that you would expect from a parent in that situation. I was trying to think about what I could do, and I realized that I wanted to tell a story. I wanted to inspire Naomi and maybe others like her to persevere.”

Ethan is a comic book writer. In the hospital cafeteria, he wrote down an idea on a piece of paper: “A girl who doesn’t know if she wants to live is the only one who can save all life on Earth.”

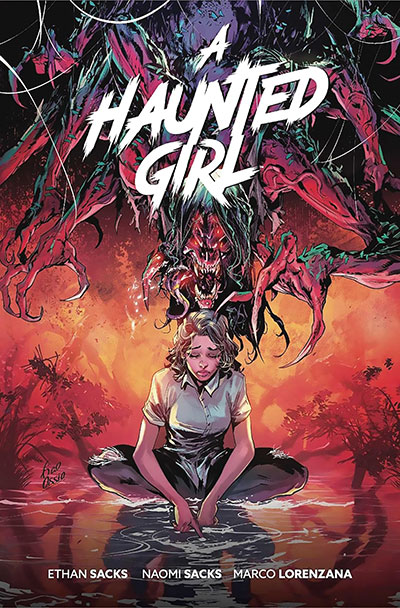

Four years later, that idea became a four-part comic book miniseries called A Haunted Girl. On May 21, the miniseries will be available in one volume as a trade paperback.

Though Ethan was initially expecting to write the story on his own, Naomi was in a very different place after receiving treatment and going through therapy. She was able to write the story with her dad, bringing her own authentic experiences to the main character, Cleo. Naomi is now in her second year at McGill University.

The story of 16-year-old Cleo fighting a supernatural apocalypse begins in a psychiatric hospital, where she has been hospitalized due to major depressive disorder. The first issue follows her and her father as Cleo is released from the hospital, meets a new therapist, and struggles to reintegrate into her old life, including returning to high school.

In recent years, mental health has been more prominent in pop culture, Naomi pointed out. But usually, stories focus on how people are struggling with mental health challenges. “There’s not a lot of representation of actually getting help or what that might entail,” she said. “This is just one story and just one possible path, but I hope it makes recovery and healing more concrete and tangible for some people.”

In the comic, Cleo relies on different support systems, including her therapist and a guidance counselor at school. Naomi said she hopes showing different potential pathways through which a teenager could seek help might demystify the process for someone who is too scared to reach out.

In terms of the mechanics of the story, Ethan said it was important that Cleo’s character arc focuses on her finding the perseverance to solve the overarching supernatural problem, but not suggest that, at the end, Cleo is suddenly “cured” of her mental illness. “I really wanted to show that she’s still struggling at school and it’s still hard, but she has support,” he said. “There is some resolution, but also the idea that there’s nothing wrong with you if you’re still struggling.”

APA Assembly Speaker Vasilis Pozios, M.D., a

comic book writer himself, provided a sensitivity reading of the series before it was published to help ensure that it did not inadvertently worsen stigma. Pozios also wrote a note that is included in the trade paperback. In the note, he encourages readers to check out the APA Foundation’s

Mental Health Care Works website, where they can find stories of recovery, information on different types of treatment, and guidance on speaking with doctors about mental health concerns.

Pozios said that a common message reinforced in the media today is the idea that it is O.K. to not be O.K. “I think that’s true, but I like to take it a step further,” he said. “It’s O.K. to not be O.K., but it’s not O.K. to suffer. It’s not O.K. to not get help, and here is how you can get help.” Showing positive stories of recovery and treatment can make a big difference for many, he said.

“Mental health has become a really popular topic to incorporate into entertainment media, to the point that some would say it’s becoming a trope,” Pozios said. “But when it’s written from the point of view of someone with real, lived experience, it becomes authentic, and people connect with authenticity. I think that’s what separates A Haunted Girl from other fictional media that might be tackling mental health issues: It comes from a place of authenticity.”

The final issue of A Haunted Girl was released in February, and while Naomi was in school, Ethan traveled to a few cities around the country for signings. “In every place I went, there were a couple of people who came up to me and said, ‘I have to tell you: I was hospitalized, and I really related to this story,’ ” he said.

A story that especially sticks out to him occurred at a comic bookstore in Annapolis, Md. A teacher told him that he had purchased several copies for his students. One of his students, after reading the issue, called the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, whose information is included in each issue.

“To me, no matter what the sales are or anything like that, I know it was a success because one person, at least, was made slightly better for this story we wrote,” Ethan said. ■