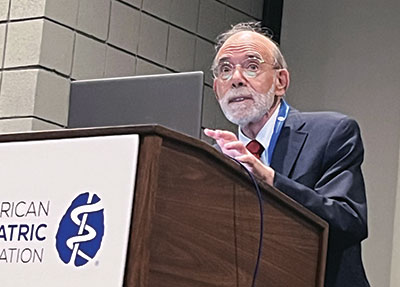

Development of clear guidelines by professional organizations such as APA is needed to mitigate the risks of ethical improprieties associated with psychedelic-assisted treatment of mental illness, said past APA President Paul Appelbaum, M.D., at APA’s 2024 Annual Meeting.

He said ethical concerns are going to grow about the use of psychedelics as they move into the clinical realm and regulations are necessary. But physicians should not rely on the FDA alone to fill the void.

“We are going to have to regulate ourselves, and our professional organizations have a role to play in developing guidelines to help clinicians,” Appelbaum said. He is the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and former chair of the APA DSM Steering Committee. Applebaum is a signatory to

The Hopkins-Oxford Psychedelics Ethics (HOPE) Workshop Consensus Statement.

Also speaking at the session were Natalie Gukasyan, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, who spoke about studies of psilocybin-assisted therapy that she helped lead at the Johns Hopkins Behavioral Pharmacology Research Unit; and Amy McGuire, J.D., Ph.D., director of the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy and head of the Ethical and Legal Implications of Psychedelics In Society (ELIPSIS) program at Baylor College of Medicine.

Appelbaum outlined broad ethical concerns about informed consent in studies of psychedelic compounds, how to ensure appropriate use, and the effect of exclusion criteria in clinical trials on communicating risk of adverse effects.

“I would suggest that for patients to provide a meaningful consent, they really need to understand and appreciate likely effects that the treatment is going to have—but there’s a challenge because some of the effects of psychedelics are inherently difficult to convey,” Appelbaum said. He cited such ineffable experiences as “oceanic boundlessness,” transformation of awareness, dissolution of ego, and shifts in values or personality that are sometimes reported by psychedelic users. “How do we deal with the reality that these are very difficult experiences to convey?”

Informed consent also requires prospective patients to know and understand what may happen in the course of the psychedelic-assisted therapy session itself. “Therapeutic touch” is often employed when patients become highly anxious or fearful. “Touching patients is something that we are all discouraged from doing in our training, and it is not concordant with the usual mainstream approaches to treatment particularly in psychotherapeutic settings for good reason,” Appelbaum said. He added that patients can be highly suggestible under the influence of psychedelics, and boundary violations are not unheard of.

Moreover, there is the more fundamental problem regarding advance planning of what patients want or don’t want to happen in the unpredictable setting of psychedelic use. “Advance planning needs to anticipate that the psychedelic experience can’t be aborted or changed due to adverse experiences,” he said.

Appelbaum noted that as part of the FDA’s review of a medication for specific indications, some data on potential adverse effects are typically available from the clinical trials. Although that’s true to some extent for psychedelics, studies often exclude participants with personal or family histories of major psychiatric disorders (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) or substance abuse, he said.

In a 2022

article in

Nature, Appelbaum noted that groups excluded from clinical trials are very likely to seek psychedelic treatment anyway, and lack of data on vulnerable populations will make formulation of guidelines difficult.

In the same article, Appelbaum wrote, “It appears to be imperative to begin collecting data under controlled conditions about use of psychedelics in populations that are very likely to be receiving them once they are available for clinical use.” ■