The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) no longer uses the diagnosis of Polysubstance Dependence, but in clinical practice, patients who use more than one substance are still very common and a source of challenge in treatment and diagnosis.

The most common combination involves tobacco use added to other substances, but polysubstance use can entail any combination of alcohol, stimulants, cannabinoids, etc. It is estimated that 13% to 14% of primary care patients have multiple substance use disorder (MSUD), with a 7.8% overall prevalence of lifetime MSUD. Every added substance increases odds of complications and adverse issues: the odds of suicide are two times higher for those with tobacco use disorder, 5.8 times higher for those with alcohol use disorder, 5.3 times higher for those with drug use disorders, and 11.2 times higher for those with combined alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders. Some specific combinations carry significant risks, such as the use of methamphetamine and opioids, which may have contributed to the marked increase in overdose death rates between 2012 and 2019. Overall, assessment and treatment for MSUD is essential to reduce the risk of overdose, suicide, high-risk behaviors, co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and other medical conditions stemming from use. This special report will focus on the intricacies of treating individuals who utilize multiple substances.

Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

The first challenge for the treatment of polysubstance use is a lack of research on the subject. Studies tend to focus on the treatment of one specific use disorder, and this limits their applicability in real life. While effective FDA-approved treatments are available for some substances (such as buprenorphine for opioid use disorder and naltrexone for alcohol use disorder), the effectiveness of these treatments in people using other substances concurrently tends to be more limited. Additionally, complex polysubstance use may include both intentional and inadvertent exposures, which treatment plans do not account for.

The specific interactions that occur between substances taken together may often have poorly understood clinical implications that may affect treatment outcomes. Short-term effects include the different substances affecting the metabolism of each other (in the case of tobacco smoke and caffeine). Also, mixing multiple substances can lead to the formation of compounds with increased intoxication effects. For example, when alcohol and cocaine are mixed, a more potent compound, cocaethylene, is created. A common longer-term effect includes how the presence of an active methamphetamine or benzodiazepine use disorder reduces a patient’s ability to stay in successful opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment.

Management of polysubstance use starts with a thorough history taking. Treating patients taking multiple substances is more complicated than just trying to treat each substance use disorder individually, as there may be a synergistic interaction between the substances that requires a more nuanced approach. Just as it is critical to identify the complex interplay between various psychiatric conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and bipolar disorder, the history taking must also reflect the complex interplay between the different substance classes. Some considerations include:

•

Which substance has caused the most cravings? One can consider identifying the various substances of interest and “ranking” them based on the patient’s historical level of cravings. For example, craving for opioids is an “8 out of 10,” methamphetamine is a “7 out of 10,” and cannabis is a “2 out of 10.”

•

Which substance has caused the most life/health dysfunction? This may also be subjectively ranked by the patient with the guidance of the interviewer as a process that may also encourage reflection and increased insight by the patient when done in a collaborative manner. Those substances that have led to near-lethal overdoses could be considered to be at the top of this list.

•

In those substances that have led to near fatal overdose, which one(s) were involved? Exploring this may reiterate the risks involved with polysubstance use and allow the clinician and patient to further identify lethal drug interactions.

•

Which substance is considered “primary”? This may be a substance that someone takes first, after which the others follow. Some may refer to this as the “gateway” substance. One example is where an individual has the strongest compulsion to use cocaine and only uses alcohol to reduce irritability from cocaine intoxication. Targeting alcohol as the “primary” and reducing its consumption may lead to some benefits in reducing secondary cocaine use. Another example would be where one identifies heroin as being the primary substance, and the secondary use of stimulating methamphetamines is aimed at reducing the sedating effect of heroin.

•

In a nuanced substance use history, do not assume that everyone knows the pharmacological names of medications in each substance class. For example, instead of asking “Do you use opioids?” It may be more helpful to ask, “Are you familiar with opioids, which may include medication such as morphine, codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, heroin, fentanyl, etc.?” Different compounds within the same class of substances may also have different treatment implications. For example, those with a use disorder for Kratom (a compound with opioid-like properties) may not require as high of a dose of medication to treat compared with a use disorder for fentanyl (an opioid with a much higher potency than Kratom).

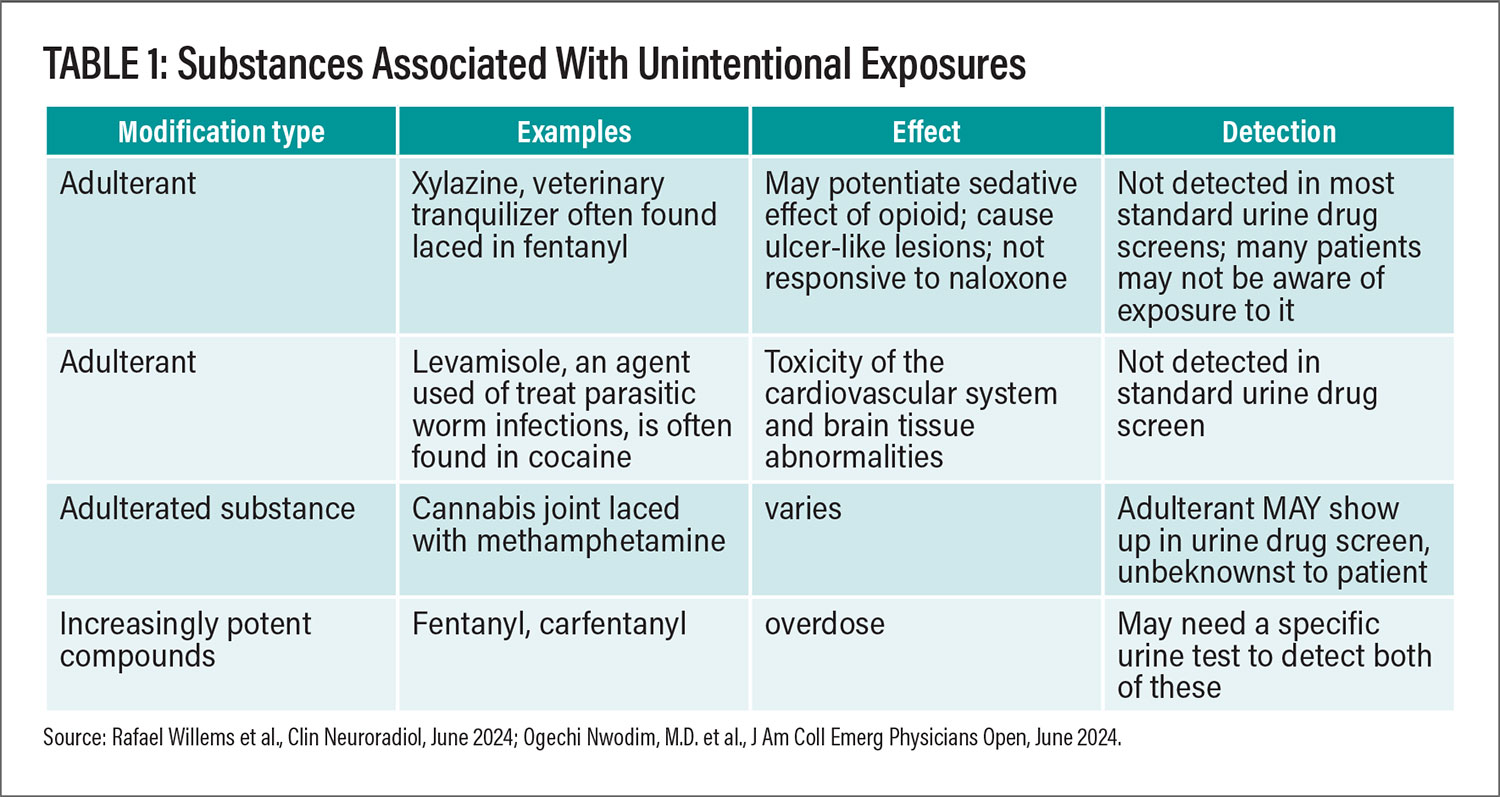

The ever-changing illicit drug industry adds an additional layer of complexity in treatment due to at least three reasons: general inadvertent drug exposures due to adulterants, toxic components in the illicit substance formation process, and increasingly potent compounds that evade screening and detection (see Table 1 for some examples).

In fact, a large proportion, around 30% according to one study, found that people who have had exposure to fentanyl experienced it inadvertently. The same applies for many other substances where a patient was seeking cocaine, only to be exposed to a laced form with methamphetamine.

We have yet to fully understand how inadvertent drug exposure affects the outcome of another substance use disorder. Does the adulterant help to reinforce the use of the initially sought-after drug? Animal models may show that after specific drug exposure, animals may tend to stay in environments where they can remain exposed, even though they do not know what substance is involved. This was reflected in research where fish that were previously exposed to methamphetamine had a preference to stay in water with methamphetamine residues.

Similarly, can humans also be prone to seek the same venue or drug source even if they are not aware of the specific drug they are being exposed to inadvertently? Thus, urine drug screens are a helpful tool in collaborative care with a patient, where it’s framed as an objective result that can help identify these exposures. The caveat is that the clinician must be aware of how to expertly interpret drug screen results, since false positive errors exist (where a drug screen shows positive results even though there is no drug in the sample).

Diagnosing mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders can be difficult when there is ongoing substance use, or even when the patient is in remission/abstinent. An estimated half of adults with mental illness also have an SUD and vice versa. This leads to the clinical question of “chicken or the egg” where one must determine if the depression led to the use of substances, or if the substance use is causing depression. Prolonged psychosis, such as paranoia and hallucinations, commonly occurs even after abstinence of drugs such as methamphetamine and cannabis. In fact, a large study from Finland found the risk of conversion from a diagnosis of substance-induced psychosis to schizophrenia spectrum disorder to be 46% for cannabis and 30% for amphetamine.

Treating comorbid disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that may require treatment with potentially addictive substances such as stimulants may be a source of hesitation for many providers, especially if there is a coexisting methamphetamine or cocaine use disorder. However, many of those who have untreated ADHD may self-treat with non-regulated substances like cocaine or methamphetamine, and there is adequate evidence that untreated ADHD can actually be a risk factor for development of a substance use disorder.

One approach to distinguishing psychiatric symptoms induced solely by drugs, from a separate psychiatric diagnosis not induced by drugs, is to focus on periods of abstinence. Controlled environments such as long-term residential treatment programs, incarceration, or prolonged hospitalizations may be periods of time to evaluate for ongoing psychiatric symptoms during those times of assumed abstinence. If abstinence itself leads to a complete or near-complete resolution of symptoms, a substance-induced episode should be considered. However, the caveat is that abstinence may also not be assumed in some of these controlled environments. For example, in the prison system, an ongoing variety of substance use still occurs, ranging from roach spray, to illicit pharmaceuticals, to misuse of prescribed medication, to hand-made substances (extracted alcohol, “prison wine”), etc.

In many cases, there may be an existing non-drug-induced psychiatric condition (such as major depressive disorder) with an overlapping component of substance-induced depression. In these situations, to assume that depression will disappear with substance reduction alone would be detrimental to the patient’s recovery. In this scenario, it is likely that the patient would benefit from antidepressant treatment to treat the underlying depression and therefore reduce risk of returning to substance use.

Treatment Principles

The framework for treating multiple substance use disorders requires several principles. Patient and clinician should identify the benefits and risks of each potential intervention, including medication. Secondly, a harm-reduction approach assures that even if a patient is not ready to stop using, then techniques to reduce physical and mental harm (and therefore safer use) can be adopted. Finally, maintaining rapport with the patient through success and setbacks is crucial for treatment retention.

While psychotherapy treatments may be helpful, making medication management contingent upon engagement in psychotherapy may have its risks. In addition, limitations exist for certain therapies based on their cost, availability, or the patient’s ability and willingness to engage. For example, a form of therapy called contingency management (where patients may be given money, prizes, or vouchers for producing negative drug screens) has shown the largest positive effect for methamphetamine use disorder. Unfortunately, many barriers exist to successful implementation such as financial cost and ethical concerns about dispensing money/prizes in this context. Self-help and 12-Step groups (like Alcoholics Anonymous) are also a particularly important component to those with substance use disorders. Evidence suggests that the amount of engagement in 12-Step groups (fellowshipping, having a sponsor) affects outcomes. At the same time, there are risks involved in twelve step groups as well, particularly if the patient is engaged with a specific group where taking helpful medication is discouraged.

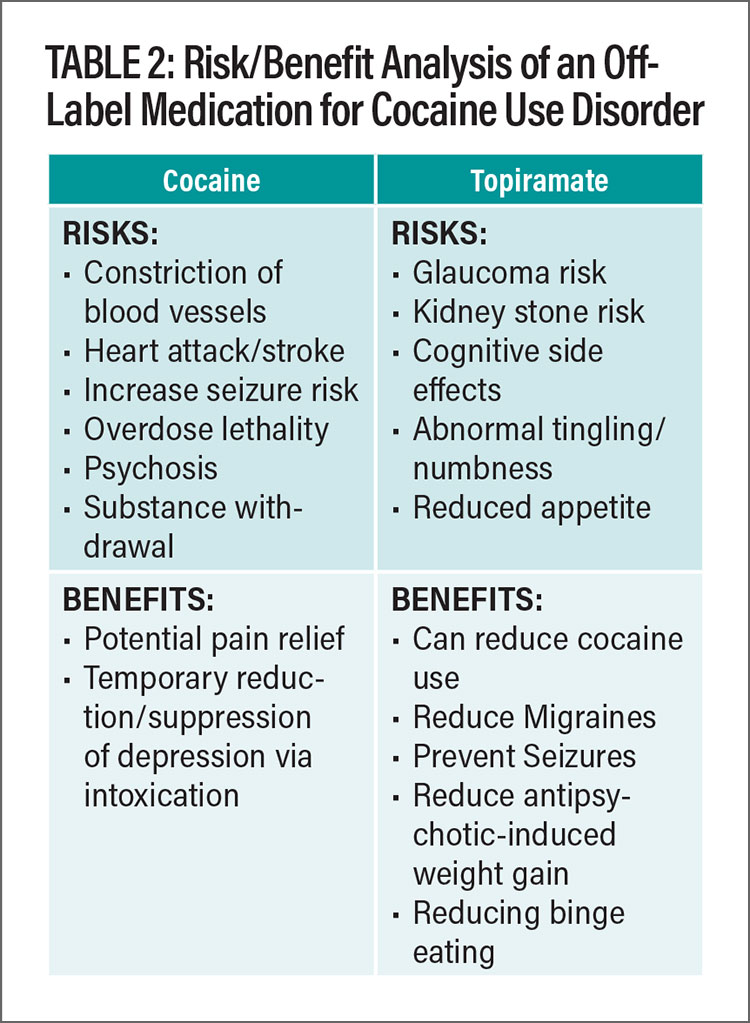

Where indicated, pharmacotherapy, both FDA-approved and off label, may have significant benefit. Within the medical community, hesitation may exist toward prescribing off-label options for SUDs. However, from a risk/benefit analysis, there may be more harm from exposure to multiple illicit substances, in comparison to a prescribed medication with known and well-documented side effects. Table 2 includes an example of the risks/benefit analysis of an off-label medication for substance use disorder. While not all effects of each compound can be included in the example analysis, some of the most common/concerning effects are noted. In this example, clinicians, as well as many patients, may agree that there are more risks to illicit cocaine than prescribed topiramate. In addition, topiramate has had some benefit in treating cocaine use disorder (in addition to other medical comorbidities such as migraines, seizures, antipsychotic-induced weight gain, binge eating disorder, etc.). This analysis must be personalized for each patient.

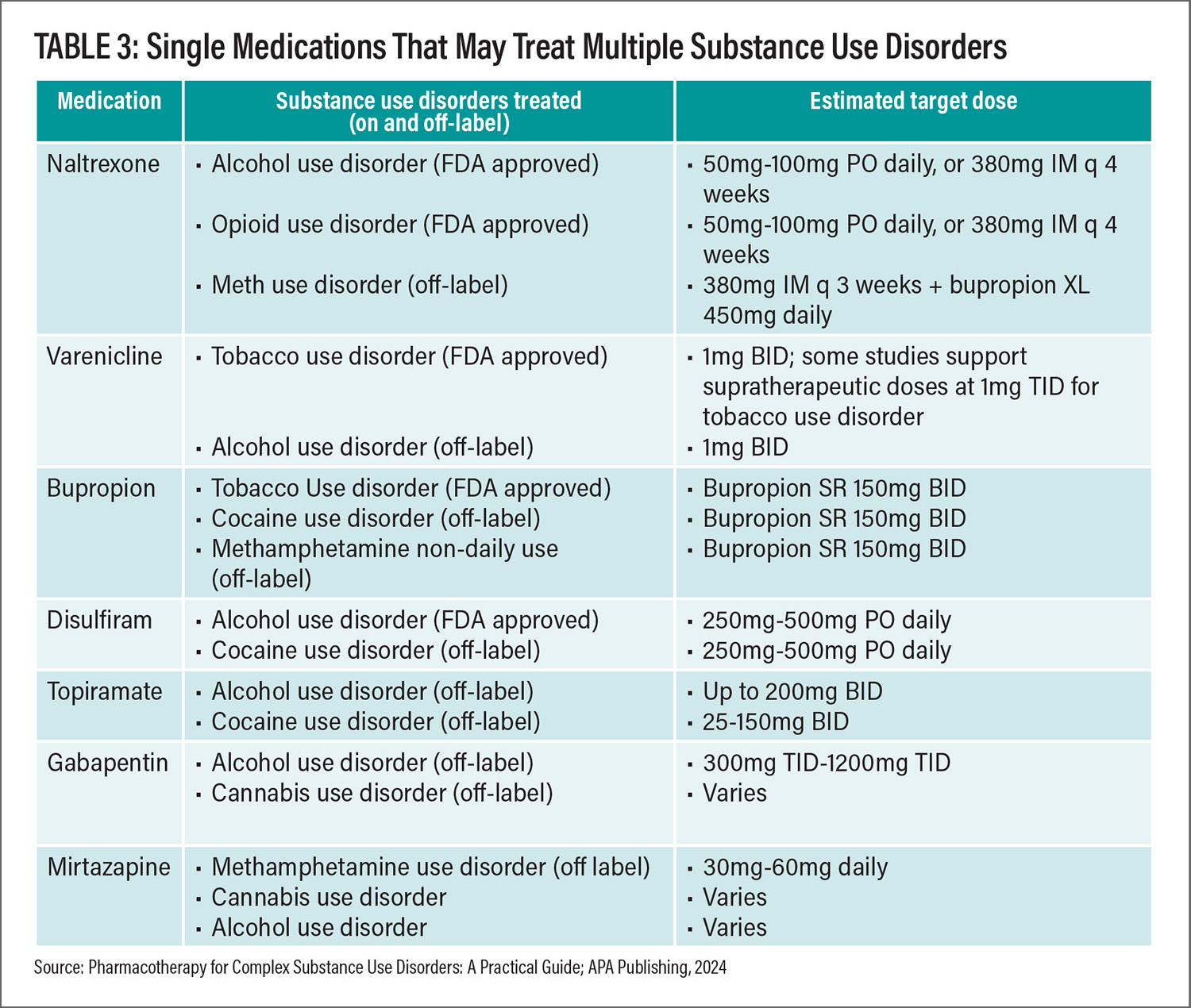

Taking a “two birds with one stone” or even “three birds with one stone approach” may be helpful to reduce the risk of polypharmacy, or a patient being on “too many” medications. It would not be particularly feasible to prescribe an off-label medication to each individual substance use disorder, especially if three or more active SUDs exist. In some cases, one medication may theoretically reduce the use of several use disorders at a time. Of note, there are no effective off-label options for benzodiazepine use disorder, hallucinogen use disorder, phencyclidine use disorder, inhalant use disorder, or synthetic cannabinoid use disorder. Table 3 provides some options as well as recommended dosing ranges.

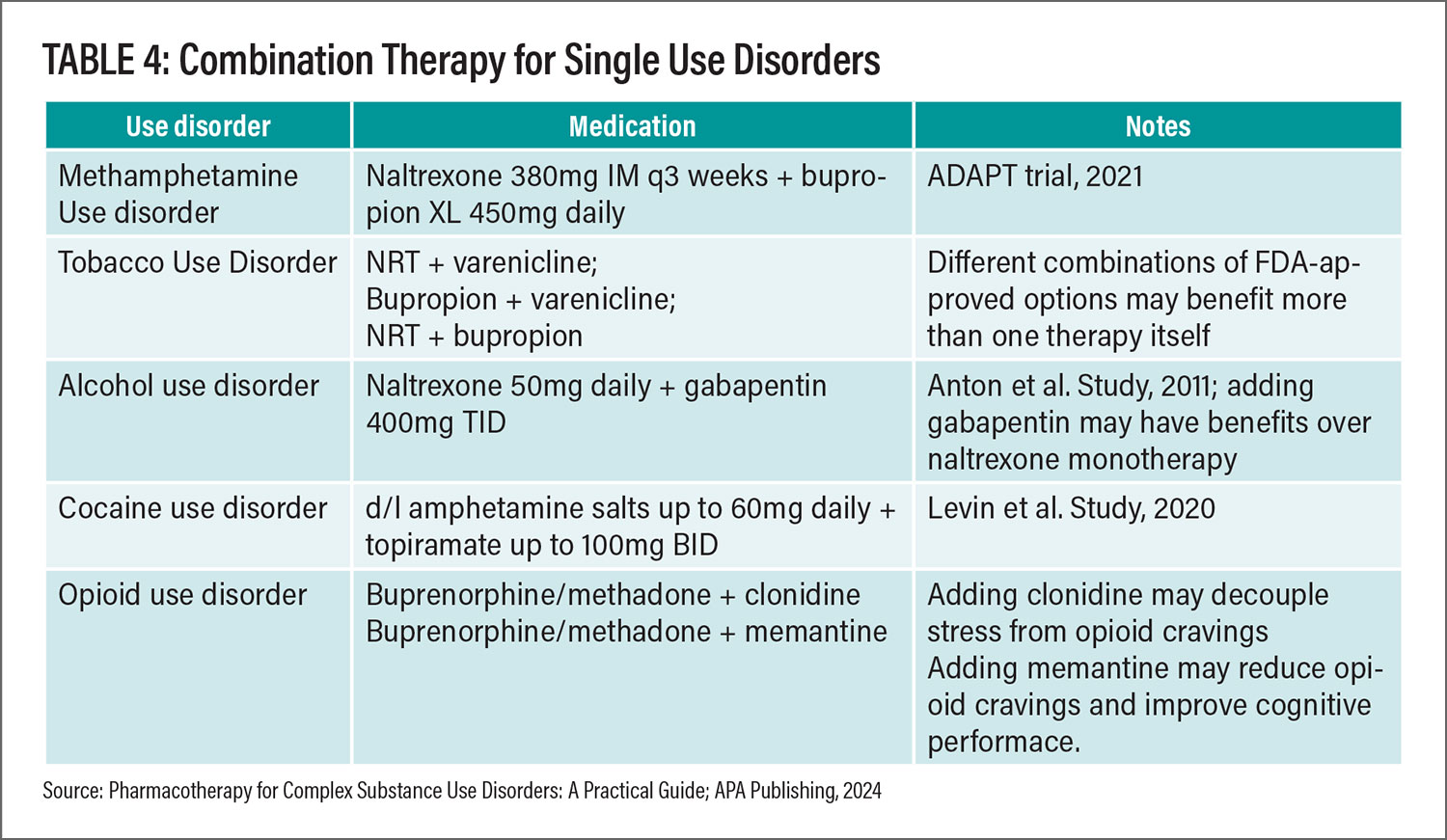

“Combination therapy” with two or more medications for the treatment of one substance use disorder is not recommended typically as an initial treatment option due to risk of polypharmacy, additional side effects, and drug-drug interactions—without any guarantee of additional benefit. For example, in one of the largest clinical trials for alcohol use disorder, the addition of acamprosate to naltrexone did not confer any additional benefit to taking naltrexone alone. “More is not necessarily better” can apply here. But in our experience, combination therapy can make a significant difference in some who do not respond adequately with one medication, so it may be warranted based on the available evidence.

Combination therapy is most widely supported in those who have tobacco use disorder, where different combinations of nicotine replacement therapy (nicotine patch, nicotine gum, nicotine lozenge, etc.), bupropion, and varenicline could have some benefit over monotherapy. Examples of combination therapy are noted in Table 4.

Psychiatrists may naturally be concerned about the risks of polypharmacy for patients with multiple use disorders. However, this may only reflect the complexity of some patients with multiple substance use disorder, and there may be continued justification for the regimen if the benefits continue to outweigh the risks. In some cases, the complex regimen is a result of months of fine-tuning. We recommend that major changes are not made to these regimens, unless the patient clearly does not want to continue the regimen, the risks outweigh the benefits, or there are inappropriate drug-drug interactions.

Conclusion

To improve the quality of life and reduce the overdose and suicide risk of patients with MSUD, we must adopt a collaborative, patient-centered approach utilizing non-stigmatizing language in order to obtain a nuanced substance use history. Expanded knowledge of laboratory testing and judicious use of information from family and friends may also help to identify patient risk and progress. While psychosocial treatments are often a helpful component of treatment, they may not be available and/or readily accepted by the patient. Regardless, pharmacotherapy is a cornerstone to reduce substance cravings and to obtain patient goals of either substance reduction or abstinence. While multiple medications may be effective for a patient, it’s important to become more adept in weighing the risks and benefits of such interventions by staying up-to-date on the literature of FDA-approved and off-label treatments for SUD. A population of patients may benefit from multiple medications to obtain stability, and from a harm-reduction approach this may be justified if the regimen effectively reduces or stops the use of multiple toxic substances. ■

References

Truong TT, Li BT, Shorter DS, Moukaddam N, Kosten TR. Pharmacotherapy for Complex Substance Use Disorders. APA Publishing, 2024.

Horký P, Grabic R, Grabicová K, et al. Methamphetamine pollution elicits addiction in wild fish. J Exp Biol. 2021; 224(13).

Willems R, You SJ, Vollmer F, et al. Toxic Leukoencephalopathy due to Suspected Levamisole-adulterated Cocaine. Clin Neuroradiol. 2024; 34(2):503-506.

Nwodim O, Karsalia R, Heslin ME, et al. Opioid-related xylazine toxicity manifesting as myonecrosis, rhabdomyolysis, multifocal ischemic cerebral infarcts, and cerebral edema. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2024; 5(3):e13187.

Magura S, Lee-Easton MJ, Abu-Obaid R, et al. Prevalence and drug use correlates of inadvertent fentanyl exposure among individuals misusing drugs in seven U.S. states. J Addict Dis. February 14. 2024. Online ahead of print.

Zhornitsky S, Tikàsz A, Rizkallah É, et al. Psychopathology in Substance Use Disorder Patients with and without Substance-Induced Psychosis. Journal of Addiction. 2015; 2015:843762.

Hersi M, Corace K, Hamel C, et al. Psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions for problematic methamphetamine use: Findings from a scoping review of the literature. PLoS One. 2023;18(10):e0292745.

Moos R, Timko C. Outcome research on twelve-step and other self-help programs. In M. Galanter, H.D. Kleber, Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th Ed.) Pp. 511-521. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Trivedi MH, Walker R, Ling W, et al. Bupropion and Naltrexone in Methamphetamine Use Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384(2):140-153.

Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, et al. Extended release mixed amphetamine salts and topiramate for cocaine dependence: A randomized clinical replication trial with frequent users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020; 206:107700.

Kowalczyk WJ, Phillips KA, Jobes ML, et al. Clonidine Maintenance Prolongs Opioid Abstinence and Decouples Stress From Craving in Daily Life: A Randomized Controlled Trial With Ecological Momentary Assessment. Am J Psychiatry. 2015; 172(8):760-7.

Elias AM, Pepin MJ, Brown JN. Adjunctive memantine for opioid use disorder treatment: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019; 107:38-43.