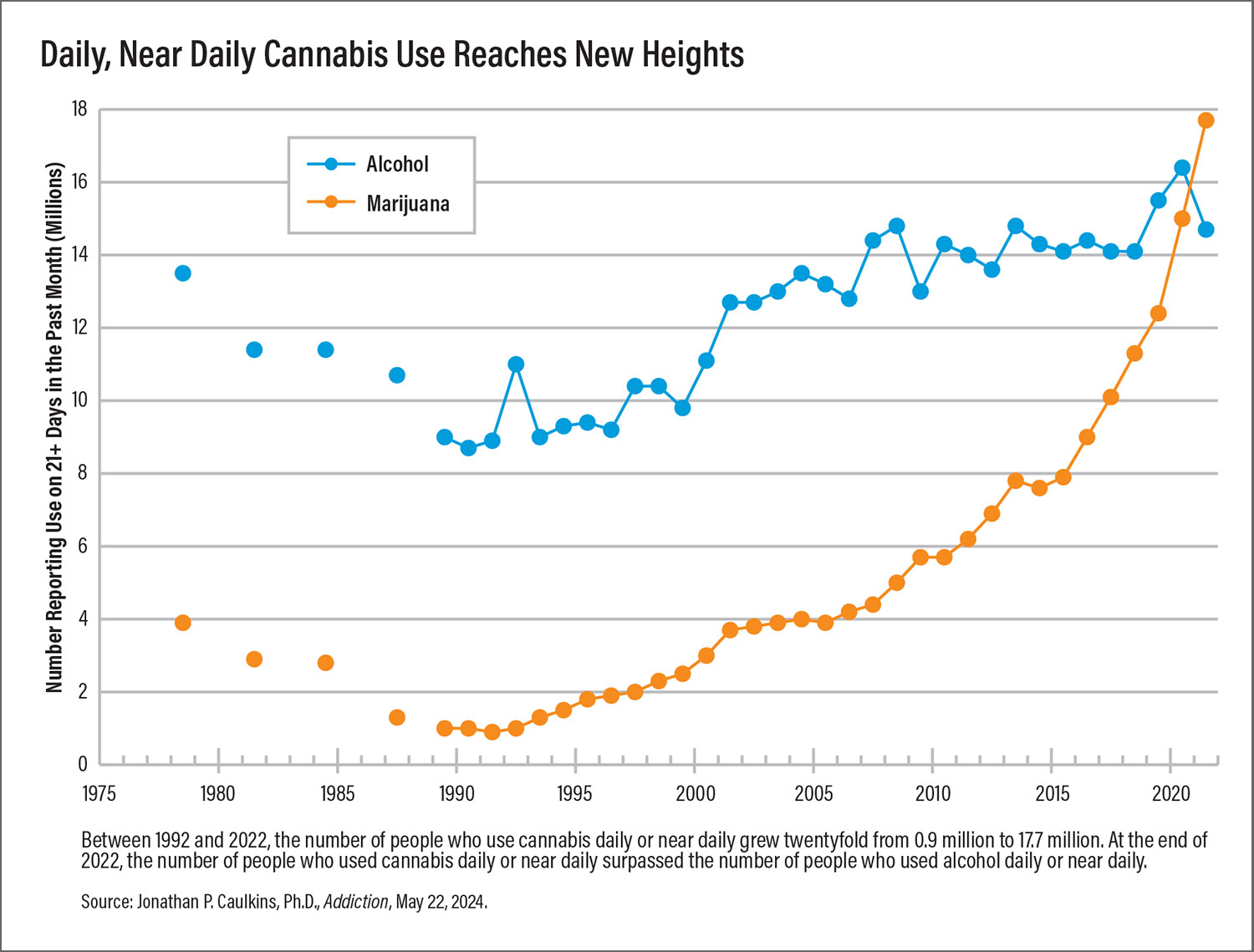

Daily cannabis use has grown in the United States such that it has outpaced daily alcohol use, a

study in

Addiction has found. The research suggests that long-term trends in cannabis use in the United States parallel corresponding changes in cannabis policy, decreasing during periods of greater restriction and increasing during periods of policy liberalization.

Jonathan P. Caulkins, Ph.D., the H. Guyford Stever University Professor of Operations Research and Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College, examined data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) since 2002 and its predecessor the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) going back to 1979. All told, Caulkins drew data from 1,641,041 participants across 27 surveys.

The survey timeframe spanned four distinct periods of cannabis policy as follows:

•

The 1970s liberalization period, reflected by 11 states decriminalizing or reducing penalties for cannabis and President Jimmy Carter appointing Peter Bourne, M.D., a proponent of cannabis decriminalization, to head the federal Office of Drug Abuse Policy.

•

The 12 years of more conservative cannabis policy under Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush from 1980 to 1992.

•

The 15 years of state-led cannabis policy liberalization (largely with respect to medical indications) from 1993 to 2008.

•

The period of explicit non-interference by the federal government beginning in 2009, up until the 2022 NSDUH.

Cannabis use declined to its lowest point in 1992, after 12 years of conservative Reagan-Bush policies. Then cannabis use gradually rose before shooting upwards beginning in 2015.

From 1992 to 2022 the number of people who reported using cannabis in the prior month rose from 7.9 million to 41.9 million. In this population, the proportion reporting daily or near daily use (21 or more days in a month) increased from 11% to 42%.

“It’s good to step back and look back at long-term trends,” Caulkins told Psychiatric News. “Even if something grows in small increments, like a stock that goes up 10% every year, it results in a big change when it accumulates over time.”

Caulkins expressed concern over the frequency of cannabis use, especially in light of increasing concentrations of THC in cannabis products.

“The average THC content of seized cannabis did not pass 5% until 2000, and now the average labeled THC content of flower [-based products] sold in state-licensed stores is over 20%,” he said. He also explained that only about 60% of legal cannabis sales take the form of cannabis flower, and the rest involve consumption of products such as edibles and vape liquid (“vape juice”) made with extracts and concentrates, which are more potent.

Caulkins added that intensive cannabis use can raise the risk of cannabis use disorder and have other negative outcomes.

“Large cannabis doses can create anxiety and panic leading to a trip to the emergency department, especially with edibles because they can have a three-hour delay in action. It’s easy for someone to take a little, feel like it’s not enough [soon after], and then take more,” he said.

Alëna A. Balasanova, M.D., a member of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry and an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, said that the study’s results were worrisome.

“What concerns me about the intensity of use is that we know that people who use high-potency cannabis every day are up to five times more likely to develop schizophrenia and other psychotic illnesses,” Balasanova said. “Meanwhile the potency of cannabis has increased over the years with little regulation or oversight.”

Cannabis vs Alcohol

When Caulkins compared the frequency of cannabis use with that of alcohol use, he found stark differences between the 1992 and 2022 surveys.

In the 1992 survey, 8.9 million people reported daily or near daily use of alcohol, compared with 0.9 million people who reported daily or near daily cannabis use. In the 2022 survey, 14.7 million people reported daily or near daily alcohol use, and 17.7 million people reported daily or near daily cannabis use. Thus, in 2022, frequent cannabis use outpaced frequent alcohol use. Furthermore, in 2022 the median survey respondent who used alcohol reported 4 to 5 days of use in the prior month, but the median survey respondent who used cannabis reported 15 to 16 days of use in the past month.

Caulkins wrote that one of the study’s limitations is that the willingness to self-report cannabis use may have increased as cannabis became normalized, so actual changes in use might be less pronounced than changes in reported use.

“Nonetheless, the enormous changes in rates of self-reported cannabis use, particularly of [daily or near daily] use, suggest that changes in actual use have been considerable, and it is striking that high-frequency cannabis use is now more commonly reported than is high-frequency drinking,” he wrote.

As cannabis use becomes more common, debates about whether cannabis or alcohol is safer have begun to emerge in public discourse and social media. Balasanova said that pitting cannabis against alcohol this way creates a false dilemma because both substances carry health risks. However, she noted one caveat.

“Alcohol has been legal and regulated in our country for a very long time, and we have policies and research to show what is acceptable use and what is not,” Balasanova said. “For example, we know that a blood alcohol content of 0.08% will impair driving and is the legal limit in most places. We don’t yet know what the acceptable limits of cannabis are for driving.”

Balasanova said that it is crucial for psychiatrists and other health professionals to ask their patients about cannabis use and educate their patients about the risks accordingly.

“Many people do not consider cannabis a drug, especially where it’s legalized, so if you ask them if they smoke, the implication is that you’re talking about cigarettes. Now you have to ask if they smoke cannabis or use cannabis products because if you don’t ask, they won’t tell you,” she said. “It’s important for people to understand that despite public opinion about the safety of cannabis use, the actual safety has not changed. It’s really not safe.”

Caulkins reported no outside funding for his research. ■