A cardiac metric known as the index of cardiac electrophysiological balance (iCEB) is more sensitive at predicting risk of a rare but potentially fatal arrhythmia in patients taking antipsychotics than the traditionally used QT interval, according to a four-year

study of hospitalized patients published in

BMC Psychiatry.

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, and stimulants are among medications that may prolong ventricular relaxation. This prolonging can induce malignant cardiac arrhythmias, including in rare instances torsades de pointes, leading to sudden death. Previous studies have shown that patients treated with antipsychotics had an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death.

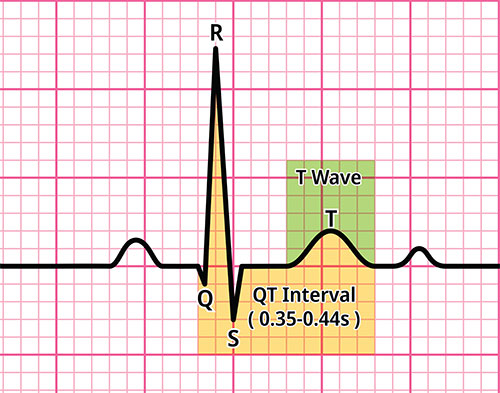

Prolonged relaxation can be readily assessed with an electrocardiogram (ECG) value known as the QT interval. This measurement reflects one cycle of ventricular contraction (observed as a rapid ECG spike known as the QRS complex) and relaxation (the T wave). But as Qiong Liu, B.A., of Anhui Medical University–affiliated Chaohu Hospital in Hefei, China, and colleagues wrote: “…[If] we only evaluate QT intervals, we may abandon some effective treatments and may also overlook some important information.”

The researchers suggested that the iCEB—which is the ratio of the QT duration to the QRS duration—was a better predictor of risk because it homes in on the balance between contraction and relaxation.

Study Methods

Liu and colleagues studied 80 adults with schizophrenia who began taking atypical antipsychotics alone or in combination with other medications after being admitted to Chaohu Hospital between 2017 and 2023. All patients were hospitalized for at least four years and underwent ECG tests at admission and every two to four weeks thereafter.

Researchers found that with long-term use of atypical antipsychotics, patients’ QTc interval and iCEBc increased over the four years. (The “c” reflects that the ECG data was corrected to account for individual differences in heart rate.) More than 90% of patients did not develop any arrhythmias, and among those who did, the iCEBc changed earlier and to a larger degree compared with the patient’s corresponding QTc change.

These findings suggest “that the iCEBc is more sensitive than the QTc and has greater clinical value in predicting the risk of arrhythmias caused by antipsychotics,” the authors wrote. However, none of the ECG reports indicated severe arrhythmia or torsades de pointes, and there were no other cardiovascular symptoms reported.

Experts Weigh In

Two experts who coauthored an APA research document on QTc prolongation and psychotropic medication and reviewed the study at the request of Psychiatric News said it poses an interesting hypothesis for further exploration but will not change their current practice.

“Right now, the recommendation from American Heart Association and other established cardiology organizations is to use the QTc interval as the best metric for estimating the risk of torsades [de pointes] and other arrythmias,” said Scott R. Beach, M.D., a clinician at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Richard J. Kovacs, M.D., Russell Professor of Cardiology and interim chief of cardiovascular medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine, agreed. “The index they examined, the ICEBc, did seem to change earlier and more significantly, so their contention that [the iCEBc] may be a more sensitive biomarker than QTc alone is hypothesis-generating, but not definitive,” Kovacs said.

“We have always tried to figure out what to do about fluctuating QRS durations when assessing ECGs,” he said.

The iCEB tested by researchers removes QRS from the equation, Kovacs explained. However, while the four-year study provided a good longitudinal outlook, it was also underpowered—with only 80 participants—to demonstrate an effect on torsades. Moreover, only about one-third of participants were women, who are far more at risk for clinically relevant arrythmias.

Another limitation of the study is that the researchers used Bazett’s formula for correcting the QT interval, Beach said. It was created in the 1920s, and while Bazett’s is still used as the default in many modern ECG machines, it has been established that the formula does a poor job of the task, particularly at heart rates significantly above 60 bpm. “So, the researchers set up the [QT interval] to fail,” Beach said.

“In our APA resource document, we have been advocating for clinicians to not take ECG machine readings at face value, but to do their own calculations using a different formula to correct for heart rate.” Opinions vary on which formula is best, but Fridericia, Framingham, and Hodges are among the better options, Beach said.

Antipsychotics Generally Safe

If anything, Beach thinks the study by Liu and colleagues reinforces the idea that antipsychotics are safe from a cardiac perspective. “However, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t monitor for this,” he said.

Patients with previous cardiac problems, particularly heart failure; or who are female, bradycardic (low heart rate), older, or sicker; or taking diuretics/prone to electrolyte imbalances (particularly low magnesium or low potassium) are at higher risk for drug-induced arrhythmia. For these individuals, Beach advises checking heart rates on the spot in outpatient settings. He also recommends that physicians consider ordering bloodwork for patients with suspected electrolyte abnormality.

The guidance for treating outpatients who are not considered high risk for torsades de pointes and who are not taking a “high-risk” antipsychotic such as ziprasidone or thioridazine is that cardiac monitoring is not needed.

What is the bottom line? Kovacs said that it is important for psychiatrists to be aware of the small increased risk of clinically important arrythmias when prescribing certain psychotropic agents, including antipsychotics. “Take advantage of a good, reproducible, safe test, and that is the ECG,” he said. “Do it properly, measure it properly, and correct it properly for heart rate.

“Then take that information and factor it into your decision making on drug choice,” Kovacs said, “using your good clinical judgement.” ■