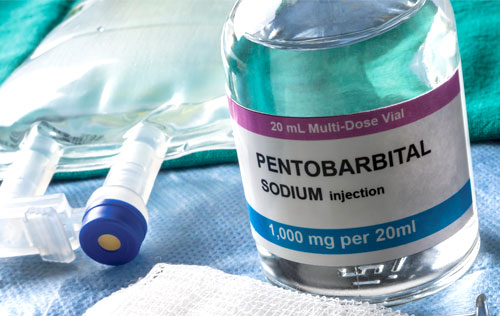

Just as national attention turns to the veterinary tranquilizer xylazine in the illicit drug supply, another substance pops up: pentobarbital.

Last spring, a reporter contacted the National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS) to inquire about pentobarbital after the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)

announced that five kilograms of the barbiturate had been among massive quantities of illicit substances seized during a 63-month Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces investigation. Researchers at NDEWS then conducted a review of potential indicators of illicit pentobarbital use and availability. Their findings were

published in

Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

Pentobarbital is primarily used by veterinarians for performing euthanasia. Its clinical use in humans is limited to indications such as managing seizures, pre-anesthesia or sedation, and short-term treatment of insomnia. However, pentobarbital has also been used off-label by several states to carry out executions and is sold underground to people who want to use it to die by suicide.

“This [substance] is of concern because there may be no way to reverse [overdoses] of it unless there is also some illicit opioid involved, in which case we can give Narcan,” senior author Linda B. Cottler, Ph.D., M.P.H., Dean’s Professor of Epidemiology at the University of Florida—which oversees NDEWS—told Psychiatric News. “We need to be vigilant.”

Putting Out Feelers

Cottler and colleagues used several methods to get a snapshot of emerging trends in illicit pentobarbital use and supply. First, they queried the NDEWS early warning network, which includes 16 sentinel sites representing various cities and states throughout the United States. In response, several sentinel site directors informed the researchers that:

•

Counterfeit oxycodone or alprazolam pills seized in Texas contained various barbiturates, including pentobarbital.

•

At least one death occurring in Kentucky between 2021 and mid-2024 was associated with pentobarbital.

•

There were three pentobarbital-related suicides in San Diego between January 2022 and May 2024.

•

A federal indictment in Chicago charged an individual with importing pentobarbital into the U.S. from Mexico to serve as a suicide drug.

The researchers also sent Freedom of Information Act requests to the DEA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and only the DEA responded before the researchers prepared their paper. The DEA informed the researchers that between 2020 and 2023, there were 259 thefts or other types of losses involving pentobarbital reported to the agency, with a total of 68,485 mL reportedly diverted. Specifically:

•

30.9% of diversions were reported thefts, such as employee theft or burglary.

•

69.1% were other types of losses, such as pentobarbital being lost in transit.

•

52.9% of diversions were from practitioners.

•

37.1% of diversions were from distributors.

Use, Exposure, and Morbidity

The researchers also reviewed annual and/or quarterly reports published by the National Poison Data System between 2020 and 2024. These reports chronicled 12 fatal pentobarbital exposures between 2020 and 2022, of which eight were reported as suspected suicides, two as adverse reactions, and two for unknown reasons. The researchers wrote that illicit pentobarbital use, exposure, and morbidity and mortality may be more common than the data currently suggest: The National Survey on Drug Use and Health stopped asking about barbiturates in 2015 in order to focus on benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, data from coroners and medical examiners is lacking, and most of the overdose- and mortality-related information the researchers were able to access was based on published case studies in which pentobarbital was found to be linked to suicide. Cottler said that one way to get a clearer picture of emerging trends in illicit pentobarbital use and availability is for more clinicians and forensics professionals to test for it—something that may be easier said than done.

“It’s unknown how many people are exposed, because they may not even know they are exposed, or they could have symptoms they don’t tell anyone about, or they may not go to the hospital,” Cottler said. “There are hospitals that use urine testing on admission, but [in general] they’re continually being asked to add more and more to the list of drugs they test for, and it could be a while before pentobarbital is added to that list.”

The study authors noted that research published in their report was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. ■