Depression is highly prevalent among those with and at risk for psychosis, with comorbidity rates ranging between 40% and 50% for individuals with a clinical high‐risk for psychosis (CHR‐P) syndrome (

1,

2). Depression and psychosis also share environmental risk factors, such as childhood trauma (

3), and genetic risk factors, with polygenic risk for schizophrenia also associating with affective dysregulation (

4). Similarly, an elevated emotional reactivity to stress and reduced motivation or effort‐cost decision‐making (

5,

6) are present in both psychosis and depression. Together, these observations suggest that depressive symptoms are highly relevant to the developmental origins of psychosis (

7).

Many studies have shown a moderating effect of depression on global functional outcomes in individuals with schizophrenia (

8), such that depression is indicative of worse long‐term global functional outcomes (

9), including a higher risk of suicidal behavior (

7) and social functioning decline (

10). Depression also shares similar cognitive impairment profiles with schizophrenia (

11), across domains of executive function, memory, and attention (

12). In particular, there is a tendency to mislabel neutral emotion in both depression and schizophrenia, thought to be driven by the negative interpretation bias in depression (

13) and impaired safety signaling in schizophrenia (

14), respectively. Thus, among patients with fully psychotic forms of illness, depression appears associated with greater severity, chronicity, and functional disability. In these cases, depression may have developed as a consequence of greater psychosis disease burden. However, depression may have the opposite association in predicting global functional outcomes within the CHR‐P population. Indeed, prior research has suggested that depressive symptoms in the early stages of psychosis may be indicative of a more episodic subtype, that is, associated with

better long‐term outcome (

6), potentially because depressive symptoms may be responsive to treatments during this phase of illness. Theoretically, an “affective” pathway to psychosis, characterized by affective dysregulation, may be distinct from a “cognitive” pathway, which may lead to a more chronic course of illness and poorer functional outcome (

15).

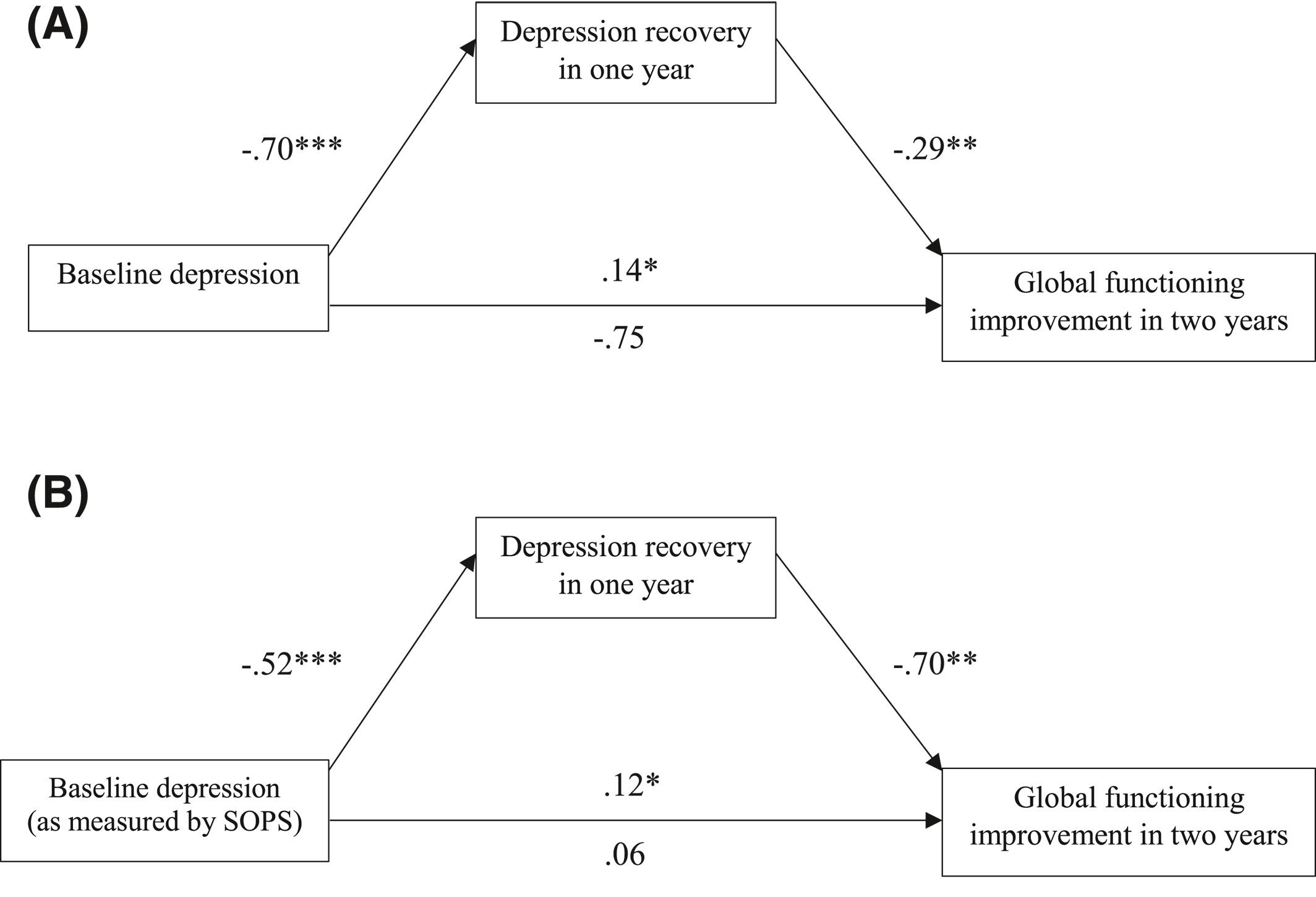

The present study aimed to investigate the roles of psychotic and depressive symptoms in predicting longitudinal global functional outcomes within the CHR‐P population, while accounting for the potentially confounding effects of baseline neurocognitive abilities and anxiety symptoms. Given that higher levels of attenuated positive symptoms are associated with a higher risk of conversion to psychosis, we hypothesized that higher levels of positive symptoms at baseline will predict worse longitudinal global functional outcomes. The two theoretical perspectives considered above yield opposite (mutually exclusive) predictions with regard to the association of depressive symptoms with long‐term functioning. If depressive symptoms track with greater psychosis‐related disease burden and chronicity among CHR‐P individuals as they do in patients with schizophrenia, higher depressive symptoms will predict more severe functional impairments over time (though perhaps not independently of positive symptom severity, given that this model predicts collinearity between psychotic and depressive symptoms). Alternatively, if depressive symptoms signal in line with the theorized affective pathway to psychosis among CHR‐P individuals, their presence at baseline should be predictive of better long‐term global functional outcomes, with reductions in depressive symptoms mediating improvements in functioning over time.

DISCUSSION

In contrast to the pattern observed among patients with schizophrenia, in which comorbid depression is associated with worse long‐term outcomes, in this study baseline depressive symptoms in the CHR‐P population were found to predict

better global functional outcomes. Furthermore, the degree of recovery of depressive symptoms in the first year following baseline completely mediated the association between depressive symptoms at baseline and functional improvement at 2 years. These findings support the view that among those at risk for psychosis, depressive symptoms may signal the presence of an affective subtype, that is, more likely to recover, perhaps because of the episodic nature of depression (

31,

32) and/or positive response to treatments.

Our findings on the functional implications of the presence of affective symptoms within the CHR‐P population differ from those among patients with full‐blown schizophrenia. Depression comorbidity may characterize worse outcomes in schizophrenia, as depression may indicate a more serious disorder presentation (

9,

33). In particular, depression may manifest as a response to prolonged social isolation and other concomitants of a more serious, fully developed form of schizophrenia. For example, worsening negative symptoms in schizophrenia may reflect a more severe impairment in effort‐cost decision‐making mechanisms. Given that such mechanisms are affected in both depression and schizophrenia, the same impairment can then exacerbate depressive symptoms associated with effort‐cost decision‐making, perhaps manifesting in the form of anhedonia and social withdrawal. In turn, patients with a heightened level of symptoms of both depression and schizophrenia may suffer worse functional impairments, have more limited social relationships, and lower quality of living than those without comorbid depression.

Our findings, together with the theorized model of affective pathway to psychosis, refute the same role of co‐occurring depression in the CHR‐P population. At an early phase of the developmental trajectory of psychosis, co‐occurring depressive symptoms predict better long‐term global functional outcomes. The fact that this relationship was fully mediated by the amount of recovery of depressive symptoms over the first year of follow‐up highlights the value of focusing on depressive symptoms in psychosis as a potential treatment target. In comparison with cognitive impairments and other symptom dimensions in psychosis, co‐occurring depressive symptoms may be more responsive to treatment and more closely associated with better long‐term outcomes (e.g., through improving social functioning and quality of life). In this naturalistic study design, participants were afforded a high degree of contact with trained clinical staff even though treatment per se was not a part of the research protocol. Those who were and were not receiving psychological and/or pharmacological treatments outside of the study protocol did not differ from each other in terms of depression recovery or functional improvement.

The differential roles between depressive symptoms in CHR‐P and comorbid depression in schizophrenia have underlined the potential importance of early identification and intervention for psychosis. The findings of this observational study raise the important possibility that providing early treatments targeting affective symptoms in the CHR‐P population may increase the likelihood for depression recovery and lead to subsequent improvements in long‐term global functional outcomes. This possibility needs to be tested in a randomized controlled study design.

It is worth noting that the amount of recovery in depression did not mediate the inverse relationship between baseline positive symptoms and long‐term functioning within the CHR‐P population. While both depression and positive symptoms are important baseline predictors for global functional outcomes, the two symptom dimensions appear to impact on global functioning through independent pathways. This pattern coheres with the theoretical distinction between the cognitive and affective pathways to psychosis. Our findings further strengthen the claim that, while severe baseline positive symptoms may predict a more chronic subtype of psychosis and worse global functional outcomes, co‐occurring depression at an early stage of psychosis risk characterizes a distinctive subtype, with symptoms potentially stemming more from affective dysregulation than neurocognitive impairments. Given the wealth of evidence‐based treatments for emotion dysregulation and depression (

34,

35), the affective subtype of psychosis has a greater potential for recovery through treatments, and could therefore be associated with long‐term functioning improvements.

While baseline negative symptoms and anxiety did not relate to the amount of global functioning changes, the two significantly predicted the direction of changes (i.e., whether global functioning improved or not) at 2 years. Our findings reveal that baseline negative symptoms and anxiety may be less robust predictors of long‐term global functional outcomes than baseline depressive symptoms in that the former are not as sensitive in explaining the degree of recovery over time. Furthermore, similar to baseline depressive symptoms, negative symptoms showed positive associations with global functioning improvement at 2 years. It is worth noting that such associations were driven by the three items in the SOPS that are closely aligned with depressive symptoms—social anhedonia, decreased experience of emotions, and occupational functioning impairments. Baseline anxiety, on the other hand, showed a similar pattern as a positive symptoms in predicting a lower likelihood of global functioning improvement over time. This is in line with the threat anticipation model of psychosis, which theorizes that anxiety may elevate stress sensitivity and prompt paranoid thinking and aberrant salience in early psychosis (

36,

37). Future studies can further explore the interaction between positive symptoms and comorbid anxiety, to better tease apart how each contributes to longitudinal functional outcomes.

It is worth noting that this study did not find associations between baseline neurocognitive or emotion recognition ability and global functioning improvement. Baseline affective symptoms predicted longitudinal changes in global functioning above and beyond fundamental neurocognitive abilities. The null findings on neurocognitive ability and emotion recognition further support that the observed functioning improvement may mainly be driven by the affective subtype of psychosis, which is characterized by affective dysregulation rather than neurocognitive impairments.

The study is not without limitations. Differential attrition is always a consideration in longitudinal studies. With an attrition rate comparable to other studies of CHR‐P samples (

38,

39), this study observed that those who were evaluated at 12‐month follow‐up had significantly higher global functioning and less severe positive symptoms at baseline than those who were lost to follow‐up. While the differential attrition limits the external validity for models predicting outcomes at 12 months, there were no statistically significant differences in demographic variables and baseline symptom scores between those who were evaluated at 24‐month versus those lost to follow‐up. Thus, differential attrition does not appear likely to explain or limit the generalizability of our findings related to global functional outcomes at 24‐month, at which point the demographic variables and baseline scores of study variables matched between those who were followed versus lost to follow‐up. Further, while the CDSS provides a good gauge of depressive symptoms overall, it may be less sensitive to detect the relation between global functioning changes and particular symptom dimensions within depression, such as anhedonia. Future studies utilizing additional measures (e.g., Beck’s Depression Inventory) may contribute to a more fine‐grained understanding of the specific depressive symptoms’ recovery that are driving the longitudinal functioning improvement in the CHR‐P population.

To conclude, the present findings support the view that depression among those at CHR‐P is indicative of an affective subtype, that is, more likely to recover and experience better long‐term outcomes. This pattern highlights the potential importance of treating co‐occurring depressive symptoms at an early stage of psychosis risk.