Sustaining remission through the use of medication of perinatal major depressive disorder (MDD) is essential for achieving optimal maternal and offspring health (

1,

2). Given the high comorbidity, clinical guidelines recommend screening for anxiety disorders in women with perinatal MDD (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7), the individual symptom trajectories of anxiety and depression vary across pregnancy to postpartum (

8,

9,

10,

11). Multilevel modeling of self‐report measures of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms reflect symptom heterogeneity within samples and identify distinct groups of women (

12), though this approach has yet to elucidate these trajectories in perinatal women treated with antidepressants, despite the large number of women who rely on this treatment modality (

13).

Studies of cohort and community samples (

3,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20) from general populations of pregnant women support three observations about the naturalistic trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms. First, a significant proportion of women (14.6% of Swedish cohort sample (

16); 42.3% of Canadian community sample (

11); 30% of a Finnish community sample (

14); and 23.4% of a Brazilian cohort sample (

19)) report chronic depression and/or continuous anxiety symptoms during the perinatal period. Second, between three to five trajectory groups emerge, characterized by descriptors of symptom severity (low, moderate), timing (antepartum, postpartum), and chronicity (stable, variable) (

3,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20). Third, the reported symptom intensity is greater in women with established depression risk factors, which include pre‐pregnancy depression, psychosocial stressors and socioeconomic disadvantage (

3,

19,

20). Collectively, these naturalistic studies show that chronic depressive and anxiety symptoms across the perinatal period may be understood as trajectories defined by symptom severity, timing, and course stability.

The expected result of antidepressant maintenance treatment during pregnancy and postpartum is the continuous control of depressive and anxiety symptoms. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants are commonly prescribed to treat MDD and anxiety disorders in pregnant women (

2); however, sustaining response during pregnancy is a clinical challenge due to its dynamic physiology and unique psychosocial milieu (

16). In the FinnBrain Birth Cohort study of >3000 women (

15), 3.1% were treated with SSRI during the third trimester. Two depression trajectory groups were identified in the SSRI‐treated women (stable‐high severity or increasing from moderate to high severity). These findings demonstrate that the SSRI are not fully effective in symptom control during pregnancy; however, the adequacy of treatment at study entry was not reported. The trajectory patterns, number of groups, and proportion of the sample of women who continue to respond to SSRI treatment across pregnancy remain undefined as prior studies did not report SSRI use (

3,

14,

16,

18,

19) or excluded drug‐treated women from enrollment (

21). Our goal is to analyze the depressive and anxiety symptom trajectories across pregnancy and after birth in women who did not have syndromal MDD at entry and who were maintained on one of the four commonly prescribed SSRI antidepressants that have equivalent effectiveness (

22).

We examine the following questions: What is the symptom course of SSRI‐treated women across childbearing? Do depressive and anxiety symptoms vary together? Do symptoms increase after birth?

DISCUSSION

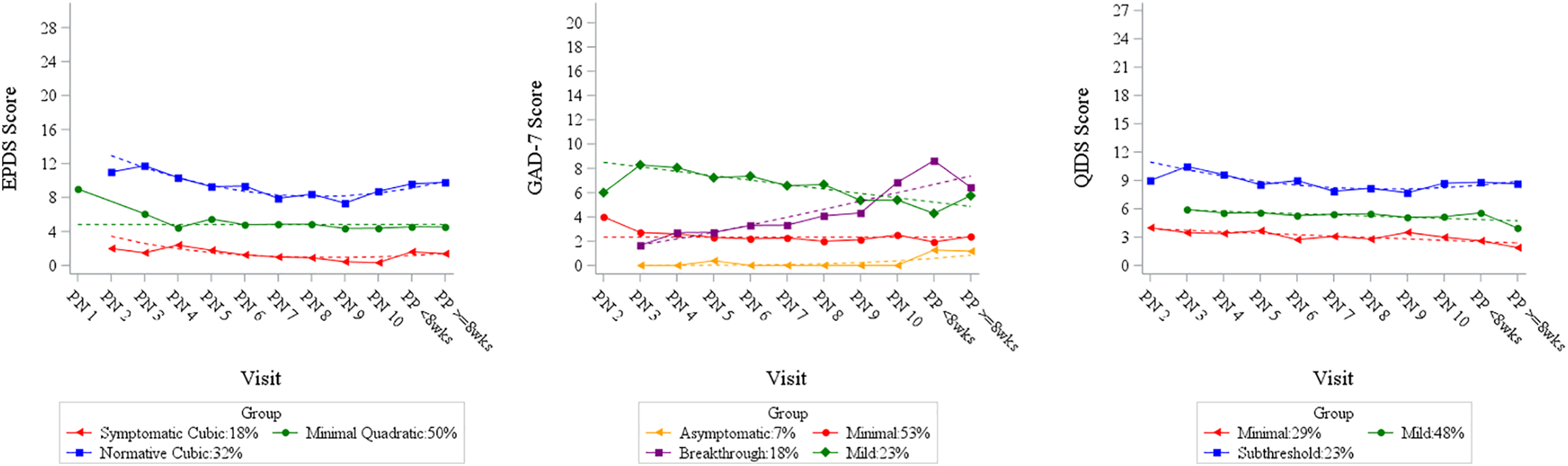

This prospective longitudinal observational study assessed trajectories of depression and anxiety symptoms across pregnancy in an SSRI‐treated cohort of women being treated for MDD. Upon study entry, the majority of participants were not in remission despite maintenance drug treatment (remission defined by DSM‐IV criteria). We identified three relatively stable trajectories of depressive symptoms across the perinatal period. In contrast, the four anxiety symptom trajectories were stable in two groups with one ascending and one descending group. Aligned with prior studies of cohort and community samples (

3,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20), our results reveal that a substantive proportion of women treated with SSRIs report depressive and anxiety symptoms, that can be discerned into three depression trajectories and four anxiety trajectories. As with prior studies (

3,

11,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20), specifiers that describe symptom severity, timing and course stability offer a systematic approach to classifying the course of perinatal conditions.

Our findings demonstrate that the treatment goal

to achieve full resolution of maternal depression symptoms remains a clinical challenge. Despite maintenance treatment, pregnant women with MDD frequently had residual symptoms at enrollment and throughout pregnancy and postpartum. Specifically, only 18% (by EPDS) to 29% (by QIDS; see

Figure 2) of the pregnant women in our cohort‐maintained remission. The justification for pharmacologic treatment of a pregnant woman is that the negative impact of the disease is greater than the risk of fetal drug exposure, such that providing drug treatment reduces disease expression and thereby its impact on pregnancy outcomes (

32). One strategy to reduce the rate of inadequate intervention for MDD is measurement‐based treatment, which is a critical component of the perinatal depression care pathway employed in obstetrical settings. Interventions are driven by serial administration of a quantitative symptom assessment tool with adaptation of the type and/or intensity of intervention until remission is achieved. This approach is particularly useful to personalize care during pregnancy, when multiple physiological and psychosocial factors are changing rapidly across childbearing.

Perinatal women with lifetime MDD have a high rate of comorbid anxiety symptoms and disorders (

6,

33). In our cohort, two of four anxiety symptom trajectories remained stable and represented asymptomatic (7%) and minimal (53%) symptom severities. The third trajectory group had high anxiety symptoms at enrollment that decreased across pregnancy and postpartum, but remained in the mild range of GAD‐7 scores (Mild; 23%). The fourth group experienced low symptoms at intake, but then showed steadily increasing anxiety (18%; Breakthrough) that peaked after birth. This investigation and increasing evidence (

5) document the co‐occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and the validity of the term perinatal mood and anxiety disorders in this clinical context. Notably, concurrent screening for both symptom sets in perinatal settings has been recommended in the United Kingdom by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Residual anxiety symptoms are common in treated depressed women and their presence extends the time to response, predicts more rapid recurrence, and signals impending relapse (

34). In our SSRI‐treated subjects, 41% had current clinically relevant anxiety symptoms, with substantially more women (18%) experiencing an increase in symptoms throughout pregnancy and postpartum compared to general perinatal populations (

3,

11,

15,

17). This group of SSRI‐treated women may represent a subgroup who, despite their low anxiety scores in early pregnancy, are sensitive to stress across pregnancy and require additional intervention to mitigate escalating symptoms as they prepare for birth (

3,

11). Residual symptoms also may result from the loss of drug efficacy due to declining plasma concentrations across pregnancy (

35). To mitigate symptoms, prescribers increased the SSRI dose in 28 of our participants, which suggests that concentrations became subtherapeutic during pregnancy. An in‐depth presentation of these results with serial plasma SSRI concentrations from these women are being analyzed for a subsequent publication.

Pregnant women with SSRI‐treated MDD experienced pre‐pregnancy, sub‐optimal health including elevated BMI and infertility, migraines, thyroid disorders and asthma. A history of eating disorders was predictive of elevated QIDS trajectory scores. Women with a history of eating disorders (

36) were at increased risk of developing perinatal depression (

37). The QIDS items that assess appetite, weight fluctuations and self‐perception likely explained this observation. Because the EPDS does not include these items, using the QIDS may better inform perinatal symptoms among women with risk for eating disorders.

This study's strengths include novel data from monthly self‐report symptom assessments through pregnancy and after birth in women who were treated with an SSRI at enrollment. This sizable population of pregnant women are frequently excluded in depressive and anxiety symptom trajectory research (

3,

14,

16,

18,

19,

21).

This study has limitations. First, the findings are generalizable to SSRI‐treated women such as those in this sample, which includes predominantly white, married, educated women. In commercially insured pregnant women, treatment with SSRIs was more common among those who were older, white, college‐educated and with higher incomes (>$100,000) (

13,

32), which describes the participants in our sample. Although Black and Hispanic women are less likely to accept drug treatment for MDD than white women, deficits in detection, engagement, treatment access and insurance coverage amplify racial/ethnic disparities in maternal mental health care (

38,

39). Studies to determine the symptom trajectories in specific populations of perinatal women at high risk of psychiatric and obstetrical morbidity are emerging to suggest ethnicity by trimester interactions (e.g., Latina women reported more positive depression and anxiety screens in the first trimester, compared to stable rates across all trimesters in non‐Hispanic Black women) (

40). The urgent need to reduce racial disparities in pregnant and postpartum Latina and Non‐Hispanic Black women are the subject of national policy attention.

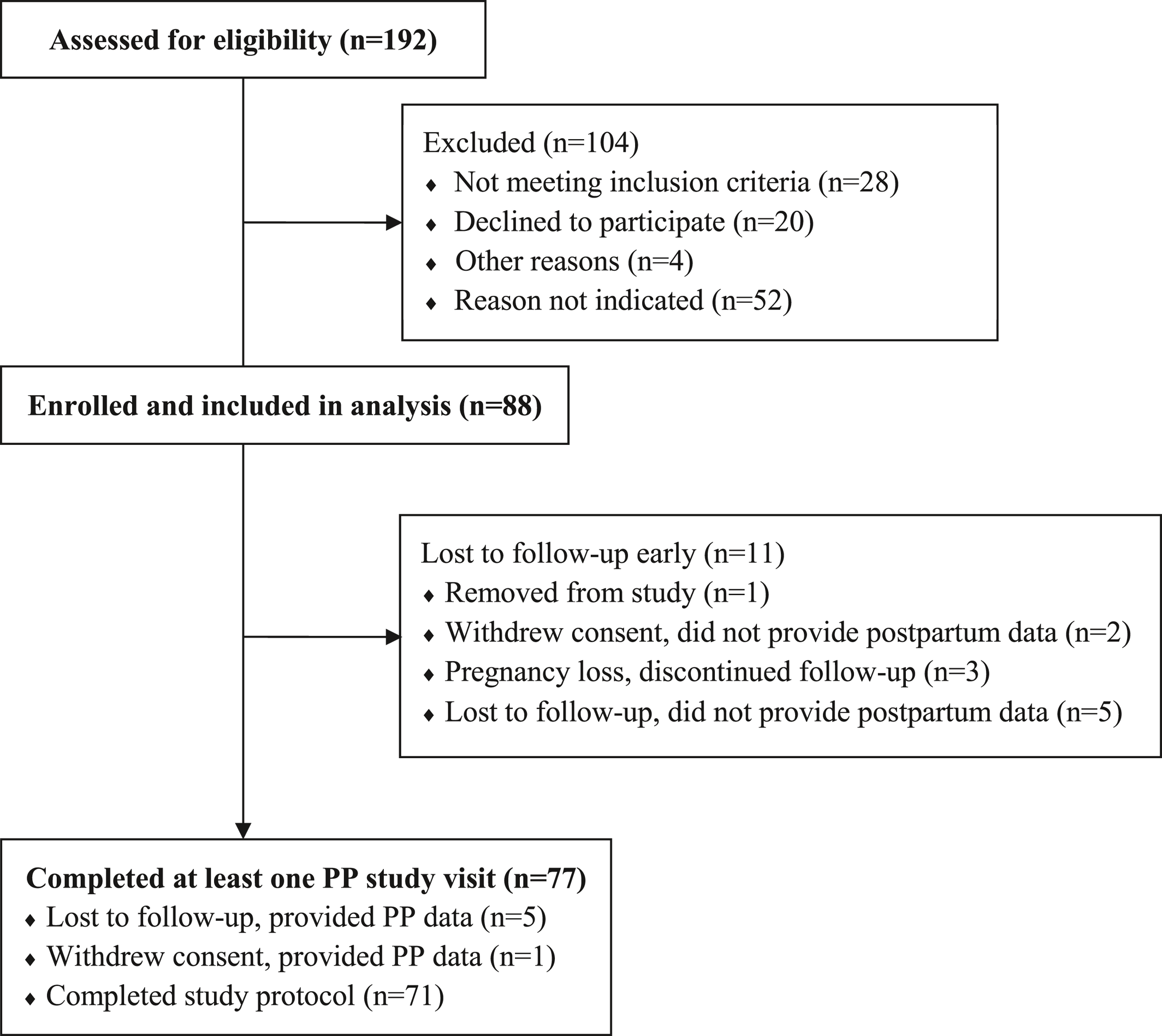

Second, we evaluated only women who were treated with SSRI and our findings are limited to this drug class. Future studies could expand this study to include women treated with other classes of antidepressants. Third, as mentioned, there were no formal sample size calculations for symptom trajectory endpoints, and we ultimately ended with a modest number of women (N = 88). However, each woman provided multiple consecutive data points which allowed for assessment of trajectory patterns in this group of women. Also, we lost 11 women to follow‐up, which prevents a complete picture of the postpartum effects. Finally, provider treatment practices, not a prescribed treatment algorithm, may have influenced our results. Future studies could intensify their tracking using biological or ecological momentary assessment approaches in lieu of self‐reports to identify endophenotypes or contextual factors related to trajectory changes. Also, future work could identify the effect of just‐in‐time treatments to constrain symptom increases across the perinatal phase.

Our findings support the implementation of measures of both anxiety and depression to obtain a more complete clinical assessment of residual symptoms during SSRI‐maintenance treatment of maternal MDD. Additional intervention research is needed to enhance the effectiveness of maintenance medication especially for women in the highest scoring QIDS and EPDS trajectories, respectively.