In our original publication in this journal,

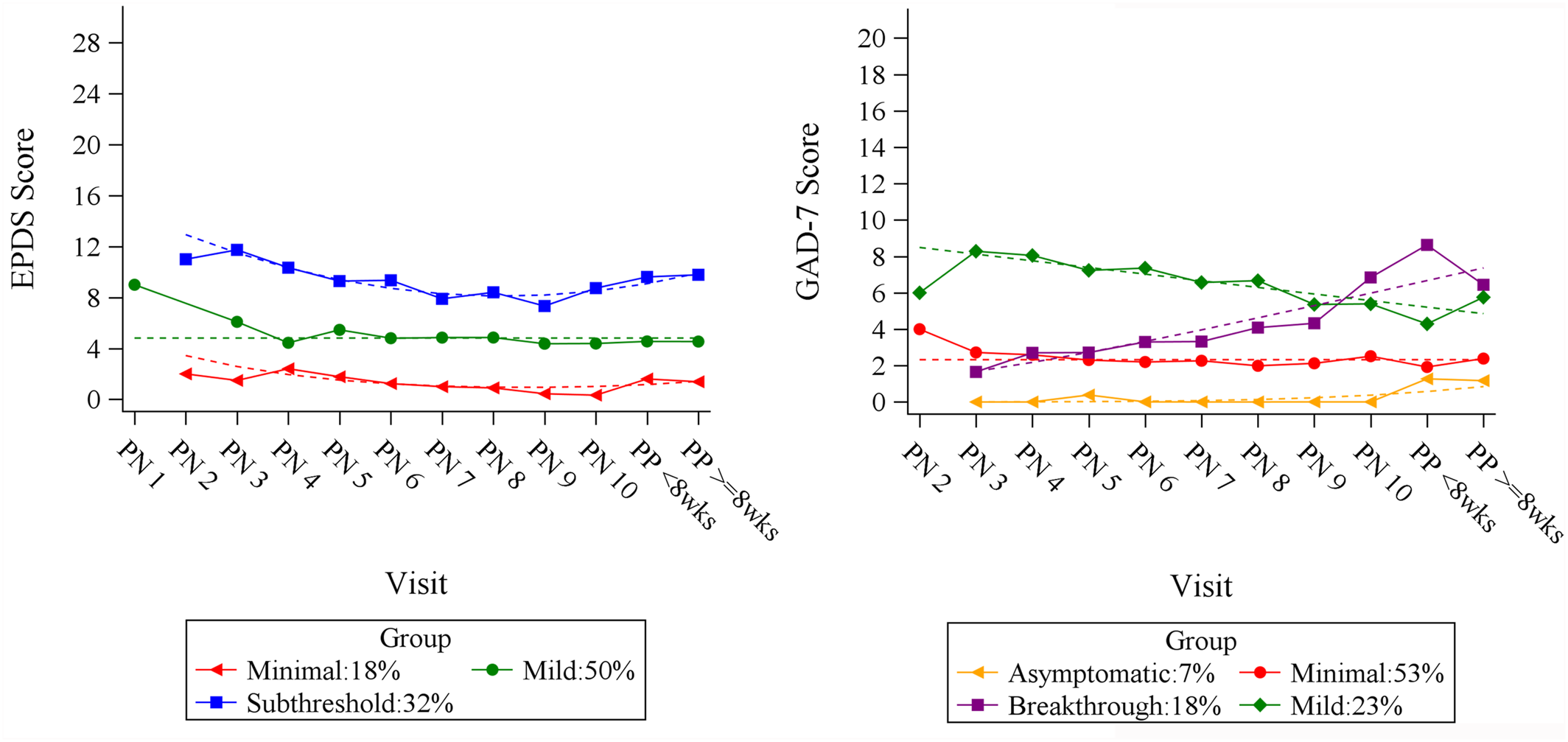

Trajectories of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Across Pregnancy and Postpartum in Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor‐Treated Women (

1), we observed three distinct depressive and four anxiety symptom trajectories from month 2 of gestation through 8 weeks post‐partum using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (

2) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder, seven item (GAD‐7) (

3) scores (

Figure 1). Although two of the anxiety trajectories were stable across the perinatal period (labeled

Asymptomatic and

Minimal), one trajectory was characterized by low anxiety scores early in pregnancy followed by ascending GAD‐7 scores (

Breakthrough), and the other showed higher anxiety scores which slowly declined (

Mild). Significant overlap in the EPDS and GAD‐7 groups was observed, with 70% of patients in the higher depressive symptom trajectory group (

Subthreshold, EPDS scores 8–12) belonging to one of the elevated anxiety symptom trajectories. Similarly, 100% of the patients in the lowest depressive trajectory (

Minimal, EPDS < 4) belonged to the lowest GAD‐7 trajectories (

Asymptomatic and

Minimal, with GAD‐7 scores < 4). In this article, we explored factors associated with the elevated EPDS and GAD‐7 trajectories to identify associations with membership in the groups with the highest symptom burdens in the perinatal period for selective‐serotonin reupdate inhibitor (SSRI)‐treated individuals.

We hypothesized that the number of past episodes of depression would be associated with the trajectories representing the highest symptom burden (i.e.,

Subthreshold in the EPDS analysis and

Breakthrough or

Mild in the GAD‐7 analysis) (

4,

5,

6). Additionally, based on the relationship of maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (

7) with perinatal depression (

8,

9), we hypothesized that higher ACE scores would be associated with the higher symptom burden trajectories. Finally, we explored group characteristics for obstetric and neonatal factors from the Peripartum Events Scale (PES) (

10) for association with higher symptom burden in the post‐partum period.

Methods

The study population included 84 pregnant individuals enrolled in the NICHD‐funded Obstetric‐Fetal Pharmacology Research Center study. As described further in the initial publication, inclusion criteria were 18–45 years of age, singleton pregnancy less than 18 weeks gestation at enrollment, diagnosis of depression, treatment with SSRI and intent to continue through pregnancy and post‐partum. Exclusion criteria included missing data, lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder or any psychotic episode, substance dependence, baseline EPDS >15 or score of 3 for self‐harm thoughts, and individuals treated with other drugs or herbal supplements.

Although the first study included 88 individuals, this secondary analysis included 84 individuals after excluding those with missing data (specifically a missing or incomplete ACE questionnaire).

We used the Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (

11) data to identify the number of lifetime depressive episodes with Wilcoxon rank sum tests. We compared the symptomatic anxiety (

Breakthrough and

Mild) and depressive (

Subthreshold) trajectories to the GAD‐7 (

Minimal and

Asymptomatic) and EPDS (

Minimal and

Mild) trajectory groups with symptoms in remission, to determine specific characteristics that differentiated patients with high symptom burden from the healthy groups maintained on SSRI treatment through pregnancy. We hypothesized that the groups with EPDS scores <5 (

Minimal and

Mild) and GAD‐7 scores <5 (

Asymptomatic and

Minimal) were in remission, therefore we did not compare groups with minimal symptoms against each other. We investigated the relationship between ACE scores of ≥3 and trajectory groups using both Wilcoxon rank sum test and bi‐variable logistic regression analysis. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and

p‐values were reported from the model. A

p‐value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We explored whether symptom increases isolated to the postpartum period may have been associated with birth trauma or specific obstetric or neonatal factors for the postpartum portions of the trajectories using the PES (

Table 1). Given the small sample size of most variables, we constructed categories based on obstetric and neonatal complications, and included a prior pregnancy loss or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission as separate variables.

Results

Adjusted for the ACE score differences, the GAD‐7 trajectory with higher symptom burden (Mild) experienced more lifetime episodes of depression compared to the groups with subthreshold symptom burdens (OR = 1.17, 95% CI 1.02–1.34, p = 0.03). The odds of being in the Mild anxiety trajectory group increased by 17% for every additional lifetime episode of depression experienced. However, the number of depressive episodes was not associated with membership in the Breakthrough versus Minimal or Asymptomatic anxiety trajectory groups (OR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.98–1.24, p = 0.10). A greater number of lifetime episodes of depression was not observed in the Subthreshold EPDS trajectory compared to the other trajectories (median three episodes vs. 2, p‐value = 0.20).

In this sample (n = 84), 22.6% of participants had ACE scores of ≥3 and 11.9% had scores of >4. No significant impact of ACE scores was observed between any of the groups in either the depressive or anxiety symptom trajectories using ACE scores of ≥3. Finally, no significant associations were identified between obstetric or neonatal characteristics, prior loss, or NICU admission and any of the trajectories.

Discussion

Congruent with other studies (

5,

6), we found a high prevalence of co‐occurring mood and anxiety symptoms and that past episodes of depression remain an important historical risk factor for perinatal symptom burden even among SSRI‐treated individuals. Less favorable trajectory membership was not attributable to ACEs or any obstetric or neonatal factors, NICU admission, or experience of pregnancy loss in our sample. Additional non‐significant covariates assessed in the primary study included race, history of anxiety, eating disorder, substance use, age, and BMI. Although prior studies of perinatal patients reported associations of higher symptom trajectories (

12,

13), this study is unique in its inclusion of only SSRI‐treated perinatal individuals.

The number of lifetime episodes of depression was associated with membership in one of the higher anxiety symptom burden trajectories (Mild) but not the other (Breakthrough). Interestingly, this was the group that appeared to have steadily higher GAD‐7 scores despite SSRI‐treatment throughout the perinatal period. The co‐occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in the perinatal period adds to the literature to reinforce that past experiences of depression increase not only the risk of future symptoms but also higher symptom burden during antidepressant treatment.

We did not confirm our hypothesis that ACE scores and obstetric or neonatal characteristics, NICU admission, and pregnancy loss were associated with symptom burden. However, this study population was largely a homogenous, White, highly educated, affluent population and does not represent the majority of perinatal individuals in the general population. Additionally, the proportion of ACE scores

>4 in our sample were lower than a similar demographic group (11.9% in our sample population vs. 23% of reproductive age women in the 2019 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data—of which 60% were White compared to 89% in this study population) (

1,

8). Overall, results from this secondary analysis of a prior publication must be evaluated in the context of a limited small sample size. Furthermore, there are limitations in assessing confidence intervals in light of this study's low sample size and associated power.

Although none of the neonatal or obstetric characteristics, NICU admission, or history of prior loss were associated with trajectory membership in SSRI treated perinatal individuals, the low frequency of these events may have limited this assessment. This dataset is unique because it is an evaluation of the trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms and associated factors among SSRI‐treated individuals.