Depression is a prevalent and morbid condition (

1,

2), and a leading cause of disability and loss of quality of life in the United States and globally (

3,

4). Primary care providers (PCPs) and practices are on the depression care front lines. In addition, safety‐net primary care clinics (those caring for people with low incomes, no private insurance, and/or special medical needs) are often the main access point to health services (including mental health) for low‐income, racial and ethnic minority patients (

5,

6,

7).

Myriad patient, provider and systems factors are barriers to depression care in primary care. Patients may not seek mental health care or may not agree with a depression diagnosis from their PCP due to perceived stigma (

8,

9). Although PCPs treat approximately 60% of people with depression in the United States (

10) and write >60% of antidepressant prescriptions (

11), many lack training to effectively treat depression (

12,

13). Studies show that a minority of patients are appropriately treated for depression by their PCP per evidence‐based guidelines (

14,

15,

16). Measurement‐based care for depression (systematic tracking of depression symptoms using validated instruments until depression remission is reached) also occurs at a much lower frequency than recommended by evidence‐based guidelines (

17,

18). Furthermore, PCPs provide antidepressant medications for shorter duration than recommended (

19), leading to inadequate treatment response or relapse. As a result, many patients treated for depression in the primary care setting will not experience symptom remission (

20) and continue to experience disabling symptoms.

The Collaborative Care Model (CoCM) addresses many barriers to depression care (

21). The CoCM is an effective model for improving depression care in primary care settings, with over 90 clinical trials demonstrating efficacy. The CoCM has five core principles: (1) patient‐centered team care; (2) population‐based care; (3) measurement‐based care; (4) evidence‐based care (antidepressants, psychotherapy, or both); and (5) accountable care (providers are reimbursed for quality of care and clinical outcomes). A multi‐disciplinary team, including a dedicated behavioral health care manager, consulting psychiatrist, and PCP, carries out the core functions of the CoCM in primary care settings. These functions include creating and maintaining practice or population‐level registries, conducting regular patient outreach and follow‐up, and ensuring adherence to measurement‐based and evidence‐based care (

22).

Although CoCM can be effective in safety‐net populations (

23) and reduce depression care disparities for racial and ethnic minorities (

24,

25,

26), multiple challenges remain to implementing the CoCM in these resource‐poor settings. These challenges include staffing constraints, inadequate financial resources to support implementation and sustainability, as well as payment or reimbursement challenges (

27,

28,

29,

30). CoCM implementation in under‐resourced settings varies widely and is less successful when insufficient staff or psychiatrist time is available (

31,

32). No prior studies describe feasible CoCM adaptations for safety‐net settings that respond to these financial, staffing and logistical limitations.

To address these real‐world financial and staffing issues, we developed a modified CoCM intervention, “Bring It Up!” (BIU), that leveraged existing primary care and behavioral health staff, rather than hiring a dedicated CoCM behavioral health care manager. Our quality improvement pilot trial sought to determine if this adaptation is feasible to implement and improves depression outcomes, compared to usual care in historical controls, in the safety‐net.

METHODS

Setting

The Richard Fine People's Clinic (RFPC) is an academic primary care safety‐net clinic at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. Approximately 40 PCPs serve nearly 9000 adults with high medical and social complexity. RFPC serves a racially/ethnically diverse population: 42% Latinx, 23% Asian/Pacific Islander, 16% white, 12% Black/African American, 1% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander and 7% other. Forty‐four percent of RFPC patients speak a primary language other than English (including 25% Spanish, 7% Cantonese, 1.9% Tagalog, 1.3% Vietnamese and 1.3% Russian). Only 1% of RFPC patients have commercial insurance; the rest have Medicaid, Medicare, both (Medi‐Medi) or Healthy San Francisco, a city health plan that makes healthcare available and affordable to uninsured San Francisco residents.

Provider Participants & Training

All PCPs at RFPC were invited to participate in the BIU pilot; we stopped recruitment once we reached our goal of seven PCPs total (three MDs and four NPs). Participating providers received a two‐hour in‐person training on evidence‐based depression care, a depression care algorithm, and the BIU pilot model of care and referral process. After this training, PCPs could refer eligible patients to the BIU team.

Patient Participants

BIU participants were enrolled as part of a quality improvement pilot between April 1, 2018, and September 30, 2018. Eligible patients were: (1) ≥18 years old; (2) diagnosed with major depression (new or existing diagnosis) with Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9) score ≥10; and (3) active patients of the seven RFPC PCPs trained for BIU. We excluded patients (1) with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, (2) receiving hospice or palliative care, or (3) permanent nursing home residents. The principal investigator reviewed referred patients to ensure they met inclusion criteria before formal BIU enrollment.

Control participants were drawn from the panel of the same intervention PCPs before BIU was implemented. We selected this historical control group to avoid spillover effect of enhanced depression management skills and CoCM depression management practices. Using a random number generator, we selected patients who received usual care from the PCP in 2017 and met the BIU participant inclusion criteria.

Development of the Intervention

Quality improvement efforts identified that baseline depression remission rates in RFPC were 3% per year, which was below the 25th percentile for the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (

33) measure of depression remission. In response, a multidisciplinary working group (a PCP mental health champion, psychiatrist, clinic panel manager, and behavioral health clinician) was formed in 2018 to develop and pilot BIU. This model was based on four of the five core principles of collaborative care: (1) patient‐centered team care; (2) population‐based care; (3) measurement‐based treatment‐to‐target (using the PHQ‐9 items with target of depression remission [PHQ‐9 <5]); and (4) evidence‐based care (

20). Accountable care, the fifth core principle, was not incorporated because RFPC's payment model does not allow for reimbursement to individual PCPs based on care quality.

Intervention: The BIU Model

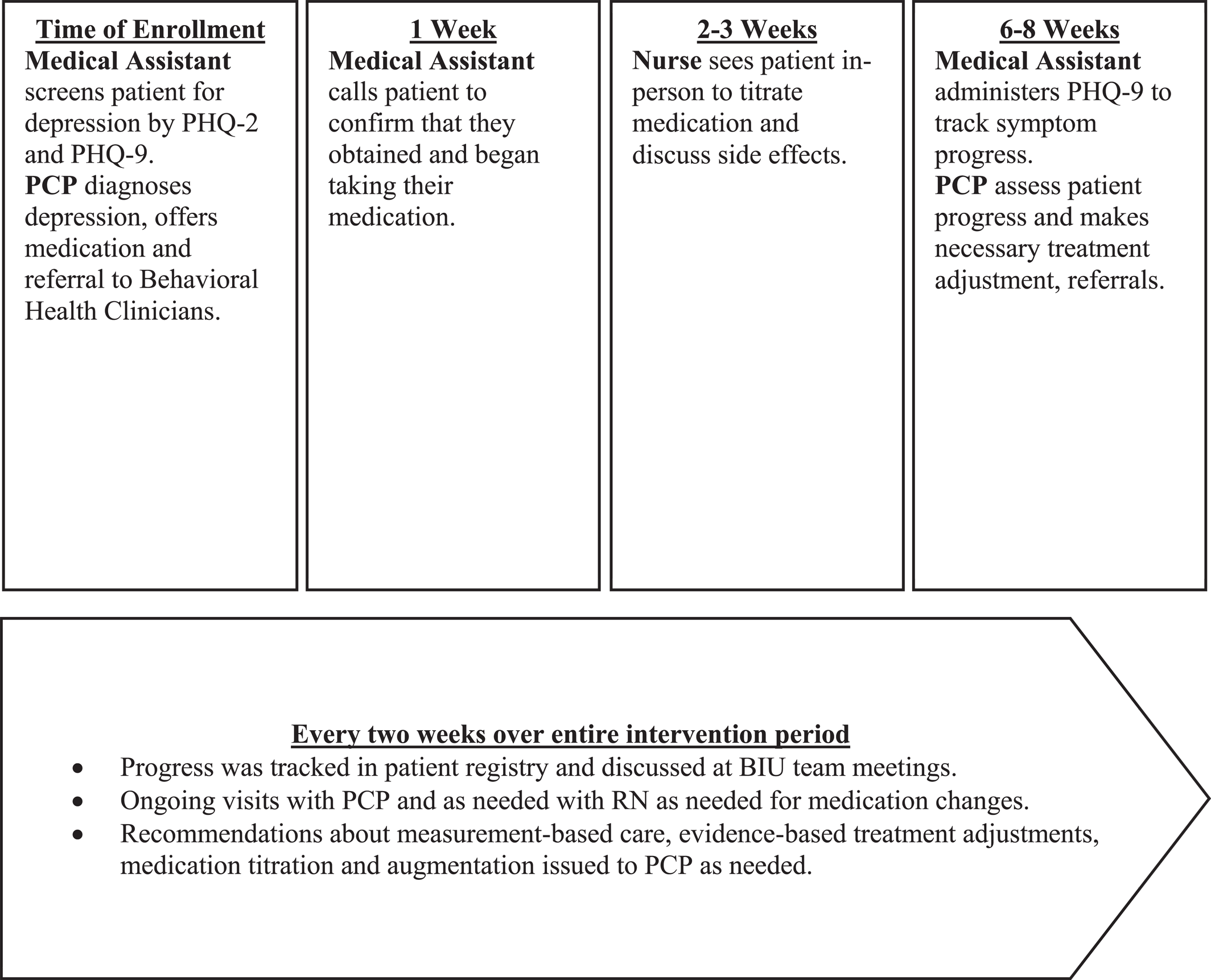

We developed and implemented an algorithm with timelines for appropriate patient follow‐up and depression management. Notably, instead of hiring a new behavioral health care manager, existing staff adopted CoCM roles and responsibilities (see

Figure 1 and

Table 1). Key intervention components included:

1.

Patient‐centered team care: BIU team members (see

Table 1) underwent a two‐hour training on the BIU model and their expected roles. Thereafter, this team met every two weeks for one hour. During meetings, the team tracked depressive symptoms (using PHQ‐9), discussed patient progress and treatment plans, reviewed adverse effects and treatment adherence, facilitated scheduling of needed additional visits, and provided psychiatrist‐generated treatment recommendations to PCPs via messages in the electronic health record (EHR) to support evidence‐based depression care. The BIU team supported enrolled patients in appointment attendance, treatment adherence and linkage to psychotherapy (behavioral activation or cognitive behavioral therapy).

2.

Population‐based care: The BIU team tracked enrolled patients using a validated, free patient registry from the University of Washington Advancing Integrated Mental Health Solutions (AIMS) center, the center that developed and champions CoCM (

20). In preparation for the team meetings held every two weeks, the clinic panel/quality improvement manager updated the patient registry with data about interim visits, medication changes, and PHQ‐9 scores.

3.

Measurement‐based treatment‐to‐target: PHQ‐9 scores were tracked for intervention participants at each provider visit. The clinic panel manager issued reminders to the primary care team to repeat PHQ‐9 administration during upcoming visits. The PCP mental health champion and psychiatrist issued treatment guidance via EHR messages with a goal of reaching depression remission (PHQ‐9 <5).

4.

Evidence‐based care: All referring PCPs received a treatment algorithm which included evidence‐based guidelines for depression care, such as timing of follow‐up, formulary medications available and guidelines for psychotherapy referral. This algorithm also included evidence‐based guidance on measurement‐based care, anti‐depressant dosing, titration, augmentation and the importance of reaching the minimum effective antidepressant dose (i.e., target dose) as defined by the American Psychiatric Association's clinical practice guideline (

34). Notably, we consider the two‐hour training of the providers (described above) critical to ensuring that all providers understand evidence‐based care.

Implementation Strategies

Several implementation strategies (

35) were employed in the BIU pilot including: (1) stakeholder engagement in design of our adapted model; (2) interactive education of the multidisciplinary team with an effective system for care team communication using the EHR; and (3) support for the clinicians through standing meetings and promoting face‐to‐face interaction between team members through co‐location.

Data Collection

Baseline and six‐month follow‐up data for all participants were extracted from the clinic EHR.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was depression remission, as defined by PHQ‐9 <5 within six months. Additional secondary outcomes included depression response (reduction of PHQ‐9 score by ≥50%) and PHQ‐9 score change (defined as the difference between baseline and follow‐up PHQ‐9 scores within six months of initial PCP visit).

We also collected information about adherence to pharmacologic treatment guidelines, including (1) antidepressant prescription; (2) medication adjustments (increased or augmented); and (3) time (in weeks) from initial visit until target dose was reached. Finally, we collected process metrics about care coordination by the team (see

Figure 1).

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline characteristics, process outcomes, and depression care outcomes between control and intervention groups using two‐sample t‐tests with unequal variances, Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests, Chi‐square test, and Fisher's exact tests. Baseline and follow‐up PHQ‐9 scores were used as assessment points for score‐based analyses. Score change was calculated by subtracting the final follow‐up score from the baseline score. An improved score was defined as having at least a one‐point reduction in PHQ‐9 from baseline. Patients who did not have a follow‐up score were excluded from score‐based analyses.

Because almost half (46%) of controls lacked follow‐up scores, we compared baseline characteristics and scores between controls with and without depression care outcomes. Due to the limited sample size, we did not test the interaction effect between demographic variables and process outcomes. All tests were conducted at the 0.05 level of statistical significance. Due to a small number of patients for certain categories, we limited the analysis to patients' gender (female or male) and language (English, Spanish, or other).

Analyses were performed using Stata/IC 15.1 (StataCorp). The study protocol was approved by University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Our study was registered with the UCSF IRB; approval was obtained for secondary analysis of existing data. Need for consent by participants was waived by the UCSF IRB per 45 CFR 46. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the UCSF IRB.

RESULTS

Sample demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in

Table 2. Our sample was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity and primary language spoken. All patients in intervention and control groups had a primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Anxiety disorders and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were common co‐morbidities in both groups, but more so in the control group. Baseline PHQ‐9 scores were not significantly different between study groups; most patients reported moderate or severe depressive symptoms. We did not find statistically significant differences at baseline between controls included and excluded from score‐based analyses.

Primary and secondary depression outcomes are shown in

Table 3. Intervention patients received increased frequency of PHQ‐9 symptom tracking; 94.4% of intervention patients completed a follow‐up PHQ‐9 in the first six months of treatment compared to only 53.7% in the control group (

p < 0.001). Of those with a follow‐up PHQ‐9 score, depression remission (PHQ‐9 <5) was achieved in 33.3% of intervention patients compared to 0% of controls (

p = 0.001). Further, 44.4% of intervention patients achieved depression response (≥50% PHQ‐9 reduction) compared to 4.9% of controls (

p = 0.003). PHQ‐9 scores in the intervention group improved by a mean of 5.7‐points over the six‐month study period compared to a 1.5‐point mean improvement in the control group (

p = 0.01). In the intervention group, 66.7% of patients had their antidepressant medications appropriately increased or augmented with a second agent according to evidence‐based guidelines compared to 26.9% of controls (

p = 0.003). Among those who were prescribed antidepressants, the time to reach target dose was similar between study groups.

Table 4 compares depression care process outcomes for control and intervention groups, including care coordination metrics described in

Figure 1. Intervention patients received increased outreach and more medical assistant (MA), nurse, and PCP follow‐up appointments for depression care compared to controls. Medical assistants conducted outreach calls for 66.7% of intervention patients; there was no MA outreach for depression care in controls found on chart review. Among intervention patients, 47.2% of patients agreed to schedule a follow‐up visit with a nurse, with 19.4% scheduled within three weeks of initial PCP appointment; 36.1% attended the registered nurse (RN) visit. On chart review, control patients did not have any RN visits scheduled for depression during the study period as part of their usual care. Intervention patients were significantly more likely to have one or more follow‐up visits with PCP for depression care (

p = 0.03) and more likely to attend their PCP visits compared to usual care patients (

p = 0.03).

The number of behavioral health visits scheduled and attended was similar between study groups. However, the intervention group had a shorter interval between date of first behavioral health referral and behavioral health appointment when compared to controls (average of 1.8 vs. 4.2 weeks) (p = 0.047).

DISCUSSION

Patients receiving this adapted CoCM intervention (BIU) were more likely to experience depression remission compared to usual care in a safety‐net setting. Notably, rates of depression remission are comparable to those described in pragmatic clinical trials implementing CoCM in primary care clinics and above the 75th percentile for the HEDIS measure of depression remission compared to our baseline of below the 25th percentile. Our study provided clear evidence of depression treatment guideline adherence as outlined in our treatment algorithm. BIU patients were more likely to be prescribed antidepressant medication, and at appropriate/target doses, with more titration and augmentation than controls. Our findings indicate that an adapted CoCM was feasible to implement with existing resources and likely contributed to the favorable outcomes over usual care.

Secondary process measure outcomes demonstrate that our adapted model maintained fidelity to the CoCM core principles of patient‐centered team care, population‐based care, measurement‐based treatment‐to‐target and evidence‐based care. Findings suggest that the BIU team‐based care facilitated more outreach and care from primary care team members such as the MA, nurse, and PCP. This high‐touch, patient‐centered care sought to reduce commonly identified barriers to depression treatment such as failure to pick up prescribed medications due to formulary problems, side effect management and/or stigma about antidepressant medications expressed by family members or friends (

36). In addition, our team successfully implemented a population‐based care tool, the AIMS center registry, to track BIU patients and monitor treatment progress. The BIU model revealed far higher rates of tracking and treating depression symptoms to target remission with a validated tool (PHQ‐9) among intervention patients than controls.

This adapted CoCM model may be advantageous for other low‐resourced settings as it leverages small amounts of time from existing primary care team members to implement the intervention. This is likely to be more feasible and sustainable than hiring, funding, and training a new care manager to coordinate the team, maintain the registry, and perform patient outreach, all key and timely functions of the care manager or proxy for this position. For example, our clinic leadership was aware of the published efficacy of the CoCM model and desired an improved depression treatment model for our patients but was unable to allocate resources to hire a dedicated behavioral health care manager. Our model is likely to be scalable and sustainable since we used a modest amount of effort from existing clinic providers and staff. This includes one of our most limited and expensive clinic resources, our part‐time psychiatrist, who was able to consult on a large group of patients through BIU.

Several limitations should be noted. First, this was not a randomized controlled trial as this project was started as a quality improvement intervention and utilized a historical control. Therefore, our results may be prone to selection bias or confounding despite efforts to select a comparable control cohort. While the study groups had similar baseline depressive symptom severity and demographic characteristics, the PCPs who volunteered to participate in this intervention may be especially motivated to improve depression care. Second, our sample size is small; we may not have achieved the same success with a larger number of patients and PCPs. However, we first wanted to ensure our pilot was efficacious before committing limited clinic resources to this model. We have now expanded the model to more PCPs and patients. Third, not all control patients had repeat PHQ‐9s due to low clinic‐wide repeat PHQ‐9 rates. This however also shows the strength of the intervention given the improvement in measurement‐based care over baseline. Fourth, the differences in enrollment date between controls and intervention group could mean improvement observed in the intervention group was a function of secular trends in improved depression screening and care due to shifting guidelines. Fifth, the control group contained more patients with co‐morbid anxiety and PTSD, potentially contributing to the relative improvement seen in the intervention group, as those with co‐morbid psychiatric disorders are less likely to achieve depression remission than individuals without co‐morbid psychiatric disorders (

37,

38). Given our small sample size, we could not adjust for co‐morbid anxiety and PTSD diagnoses. No control patient reached remission, so we could not attempt an in‐group proportion test related to those with co‐morbid anxiety. Another limitation is that since treatment was medication‐focused, it could be biased toward enrollees most motivated to start medications. Finally, we noted a significant under‐representation of Cantonese‐speaking patients in both intervention and control groups compared to our overall Cantonese‐speaking patient population. This may simply be a result of the small sample size but warrants further investigation into a possible disparity in depression diagnosis and treatment.

CONCLUSION

The BIU model, an adaptation of the CoCM for safety‐net settings, appears to be a feasible and potentially effective way to provide depression care in under‐resourced settings. Given the favorable clinical outcomes found in this low‐cost adaptation, this intervention warrants further study in a large cluster‐randomized controlled trial that analyzes clinical outcomes and cost‐effectiveness.