HIV remains a significant public health crisis in the United States with over 36,000 new diagnoses in 2021 (

1). People living with mental illness (PLWMI) experience a disproportionate prevalence of HIV, with estimates suggesting the rate is up to 10 times that of the general population (6.0% vs. 0.6%) (

2). Concurrently, PLWMI face numerous social and systemic barriers to accessing healthcare including stigma, a fragmented care delivery system, housing instability, and higher rates of incarceration, which have been consistently documented as major contributors to increased HIV vulnerability (

3,

4,

5). Comorbid substance use disorders (SUD) also raise HIV vulnerability and incidence, especially among people who inject drugs (PWID) (

1).

The past decade has seen the approval and scale‐up of biomedical HIV prevention methods, specifically antiretroviral pre‐exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (

6). An extensive body of literature has established the effectiveness of oral PrEP, which reaches rates of >95% when taken daily (

6). Furthermore, long‐acting injectable (LAI) cabotegravir administered at 8‐week intervals (following two loading doses 4‐week apart) was approved as PrEP in 2021, representing the first non‐oral option (

7). While substantial evidence supports the use of PrEP, only an estimated 30% of patients with PrEP indications used the regimen in 2021, largely attributed to stigma, limited clinician knowledge, and difficulties accessing care (

8,

9). Rates of PrEP use are much lower among minoritized sub‐groups (e.g., people of color), who experience additional hurdles such as racism and lower rates of health insurance coverage (

8). In 2021, over 75% of White patients with PrEP indications were prescribed compared to less than one‐third of Black patients (

9).

PrEP uptake is even lower among PLWMI; a recent study of a limited national electronic health record dataset found 0.3% of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were prescribed PrEP between 2013 and 2018 (

10). This is in contrast to the well‐documented HIV vulnerability associated with these diagnoses (

11). Other studies have identified connections between depressive symptoms and increased HIV vulnerability and decreased likelihood of using PrEP (

12). Recent work also demonstrated that an estimated 0.15% of PWID with commercial health insurance were prescribed PrEP (

13). Mental illness and SUD have been consistently identified as barriers to PrEP engagement among patients and as independent risk‐factors for HIV (

14).

Psychiatrists serve as the primary healthcare providers for many PLWMI, and a growing body of work supports the expansion of the range of clinical services provided by psychiatrists to include more preventive healthcare (

15). There may be a role for psychiatrists in expanding access to PrEP for HIV prevention among PLWMI. However, this possibility remains critically under‐examined as most prescriptions for PrEP currently come from primary care providers (e.g. family medicine), infectious disease physicians, and those specializing in HIV care (

16). Several previous studies have investigated barriers and preferences related to PrEP implementation among primary care and infectious disease clinicians (

8). To the best of our knowledge, no previous research has investigated PrEP prescription by psychiatrists. Additionally, a majority of work describing integration of psychiatric and HIV care has focused specifically on integration of psychiatric services for patients living with HIV rather than integration of HIV‐prevention services in psychiatric care

(14). There is growing focus on “reversing” collaborative care models to integrate primary preventive services in mental healthcare settings considering the drastic, 10‐20 years life expectancy gap between people with and without mental illnesses, largely attributed to preventable diseases (including HIV) (

17).

Prior studies have investigated availability of HIV testing in outpatient mental health care settings have found overall low availability (6.64%) (

18). Additionally, in 2021 only 5.2% of outpatient substance use treatment facilities indicated PrEP prescription was available (

19). Furthermore, less than half of the facilities that indicated HIV treatment services were available also indicated PrEP prescription was available, despite both requiring prescription and management of antiretrovirals (

19). This suggests both feasibility of offering PrEP in mental healthcare settings given existence of some available services, but also the need for expansion of PrEP availability to meet the needs of PLWMI and minimize barriers to care.

The purpose of the present study was to investigate psychiatrists' perspectives on implementation of PrEP within psychiatric care. The specific objectives of this study were: (1) Examine PrEP requests, PrEP prescription, and interest in prescribing PrEP among psychiatrists; (2) Determine barriers to PrEP prescription among psychiatrists; (3) Investigate psychiatrists' preferences for clinical models to support PrEP prescription within psychiatric practice; and 4) Evaluate psychiatrists' self‐reported confidence in PrEP‐related clinical tasks.

METHODS

Population & Recruitment

Psychiatrists were recruited via a combination of methods to surmount the documented difficulties in conducting research with physicians (

20). First, information about the study was shared via email with the American Medical Association Physician MasterFile, a large, national listserv of psychiatrists (

n = 10,840). Emails were sent up to six times including an initial message and up to five reminders if the study instrument was not completed. Geographic filtering was applied to over‐sample the

Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) priority jurisdictions given the increased focus on HIV prevention in these areas due to disproportionate HIV incidence (

21). This was supplemented by distributing information about the study at the 2023 American Psychiatric Association annual meeting (

n = 1143 U.S. attending/fellows in psychiatry), for a total of 11,983 possible respondents.

Psychiatrists were eligible for participation if they: (1) Held an allopathic (MD) or osteopathic (DO) medical degree, (2) Spent at least some percentage of their time providing direct patient care, (3) Were practicing in the U.S., and (4) Were an attending or fellow in psychiatry. Data were collected between November 2022‐October 2023. All participants received an electronic $50 Visa® gift card as compensation.

Instrument

The study instrument was developed based on review of previous studies about PrEP implementation conducted among primary care and infectious disease physicians (

22,

23,

24). Items were refined with input from experts in infectious disease and psychiatry. A focus group of five psychiatrists reviewed the instrument and provided feedback on item wording, which was incorporated before distribution. The study instrument was hosted on Qualtrics® (Qualtrics Inc., Provo, UT). The full study instrument is included as Supplemental Material.

Previous PrEP Experiences: First, psychiatrists indicated whether they were aware of PrEP at the time of the study, which was defined. Next, psychiatrists indicated whether a patient requested PrEP prescription from them, and whether they previously prescribed PrEP. If a participant indicated “yes” to either of these, they were prompted to complete a follow‐up item to estimate the number of times (1‐5, 6–10, ≥11) for each. Additionally, we inquired about interest in prescribing PrEP and interest in receiving training about PrEP (yes/no/not sure).

Barriers: A series of 12 possible barriers to PrEP implementation including six system‐level barriers (eg. insurance coverage, administrative requirements, liability) and six individual‐level barriers (eg. limited knowledge, discomfort in discussing sex, out‐of‐scope) was presented. The list was developed considering previous studies with other groups of clinicians about implementing PrEP prescription

22,

25,

26. Respondents selected all barriers they thought would negatively affect PrEP implementation in their practice.

Preferences for PrEP Implementation: A series of four models for PrEP implementation was presented (eg. all psychiatrists trained in PrEP prescription, patients referred out for PrEP, psychiatrist initiates PrEP with arranged primary care follow‐up) based on previous studies (

22,

25,

26). Psychiatrists indicated each of the models they felt were acceptable.

Confidence: Two domains of confidence were assessed. First, participants were presented with 10 PrEP‐related tasks (eg. ordering follow‐up lab testing, taking sexual history) adapted from the CDC guidelines, and previous research with healthcare professionals and trainees (

26,

27). Second, participants were presented with a series of eight items measuring confidence managing general medical conditions (GMC; eg. hypertension, non‐opiate pain management, and asthma) (

28). The GMC confidence scale was included as a baseline measure of comfort practicing outside of the traditionally defined scope‐of‐practice of psychiatry. All confidence items were phrased as: “I would feel confident…” and rated on a 7‐point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Items in each domain were averaged to create aggregate measures of PrEP‐related tasks (Cronbach's

α = 0.91) and managing GMC (

α = 0.95).

Demographics: Psychiatrists indicated their race, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, age, years in practice (including residency and any fellowship[s]), and primary practice setting. Participants also indicated the state in which they practiced. If psychiatrists practiced in a state with an EHE priority jurisdiction (counties or cities), they completed a follow‐up item to indicate if they practiced in one of these jurisdictions (

21).

Statistical Analyses

First, we calculated frequencies and other descriptive statistics to describe the sample and outcomes. We employed a series of bivariate, binomial logistic regressions to model the associations between demographic/practice characteristics, confidence in managing GMC and PrEP‐related tasks, and likelihood of: (1) receipt of a PrEP request, (2) previous PrEP prescription, and (3) interest in prescribing PrEP, followed by three multivariable models to evaluate the combined associations between all demographic/practice characteristics, confidence domains, and each outcome. For the multivariable models, adjusted odds ratios (aOR) are presented and we assessed for multicollinearity during model construction. All descriptive outcomes were repeated, separated by primary practice setting (Supplemental Figures

S1A‐2C). In addition, we performed a series of secondary analyses of the primary practice setting, barriers, and confidence comparing the group of psychiatrists who had prescribed PrEP following a patient request and the group who did not using chi‐squared tests for categorical variables and independent samples

t‐tests for continuous variables.

Analyses were completed utilizing StataMP V17 (StataCorp). A p‐value <0.05 was established as statistically significant. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Chicago.

RESULTS

A total of 1172 participants began the study (response rate = 9.78%; 1172/11,983). First, we excluded 54 responses from participants who did not meet inclusion criteria including 32 who were not psychiatrists, 12 without an MD/DO degree, and 10 who did not have any direct patient contact. An additional 238 responses from psychiatrists who did not complete the main study outcome(s) or demographic items were excluded. The final analytic sample was 880.

Demographics

Most respondents were attending psychiatrists (

n = 764, 86.8%), practiced in academic medical centers (

n = 642, 73.0%), and over half reported their primary practice setting was outpatient psychiatry (

n = 480, 54.6%). Geographically, the largest percentage practiced in the Northeastern U.S. (

n = 304, 34.6%), and in an EHE priority jurisdiction (

n = 623, 70.8%). Most completed a fellowship after residency (

n = 584, 66.4%), and child/adolescent psychiatry (

n = 228, 25.9%) was the most common. Most identified as heterosexual (

n = 724, 82.3%), as men (

n = 475, 54.0%), and as White (

n = 482, 54.8%). Mean practice duration was 14.0 years (95% CI: 13.3–14.7), mean percentage of time providing patient care was 72.1% (70.4–73.8), and mean percentage of time spent in outpatient psychiatry was 70.1% (67.7–72.6). Complete demographic information is included in

Table 1. We found 93.2% of psychiatrists were aware of PrEP.

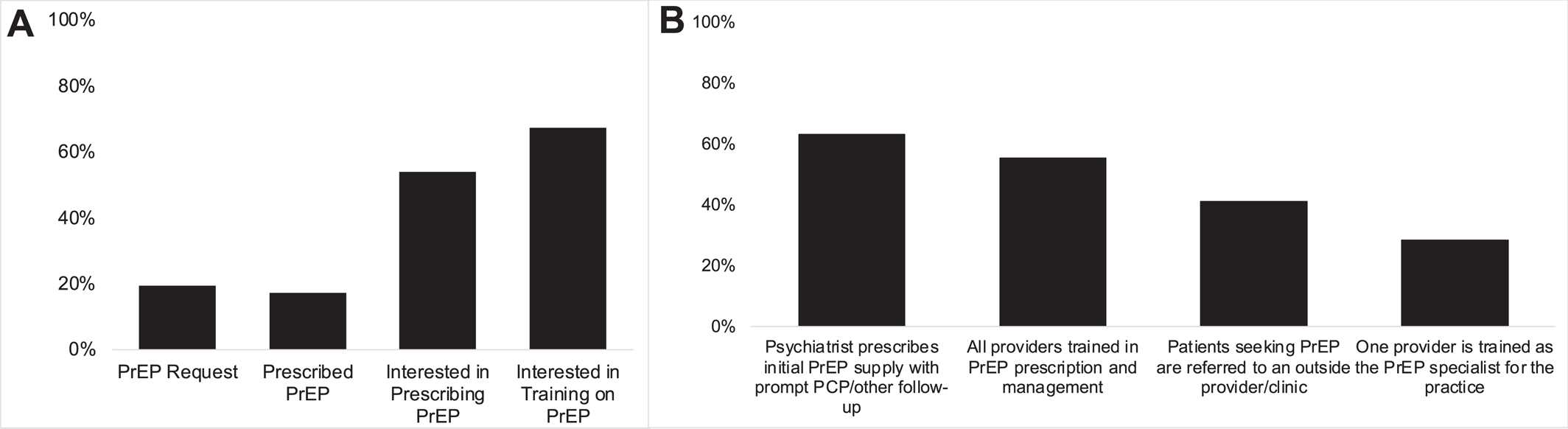

PrEP Requests

Overall, 19.3% of psychiatrists had received a PrEP request from a patient (

Figure 1A). Of these, most (72.4%) received a PrEP request between 1 and 5 times. Attending psychiatrists were more likely to have received a PrEP request (aOR = 2.08 [1.06–4.06],

p = 0.03) compared to fellows, while those practicing primarily in consult‐liaison (CL) psychiatry were less likely to have received a request (aOR = 0.33 [0.11–0.93],

p = 0.04) (

Table 2). Psychiatrists practicing in one of the EHE priority jurisdictions (aOR = 1.62 [1.02–2.58],

p = 0.04) were also more likely to have received a PrEP request. Compared to psychiatrists without fellowship training, those who completed an addiction medicine fellowship (aOR = 3.61 [1.78–7.29],

p < 0.001) or forensic psychiatry fellowship (aOR = 2.52 [1.07–5.92],

p = 0.03) were more likely to have received a PrEP request. A greater percentage of time in patient care overall (aOR = 1.01 [1.00–1.02],

p = 0.01) and greater confidence managing GMC (aOR = 1.21 [1.03–1.42],

p = 0.02) and PrEP‐related tasks (aOR = 1.76 [1.44–2.16],

p < 0.001) were associated with greater likelihood of receipt of a PrEP request (

Table 2).

Previous PrEP Prescription

We found that 17.3% of psychiatrists had prescribed PrEP to a patient (

Figure 1A), and most had prescribed between 1 and 5 times (68.4%). Of psychiatrists who indicated they received a request for PrEP prescription, 65.9% prescribed PrEP, and 5.6% of psychiatrists initiated PrEP prescription without explicit request. Psychiatrists practicing primarily in inpatient psychiatry (compared to outpatient; aOR = 2.80 [1.11–7.06],

p = 0.03), or in one of the EHE priority jurisdictions (aOR = 2.08 [1.23–3.54],

p = 0.003), were more likely to have prescribed PrEP (

Table 2). Psychiatrists who completed a CL‐psychiatry (aOR = 0.37 [0.14–0.98],

p = 0.04) fellowship (compared to no fellowship) were less likely to have previously prescribed PrEP. Greater confidence in managing GMC (aOR = 1.34 [1.12–1.60],

p = 0.001) and PrEP‐related tasks (aOR = 2.10 [1.67–2.65],

p < 0.001) were associated with higher likelihood of PrEP prescription. Among the group who had received a PrEP request but did not prescribe (

n = 58), the greatest percentage were practicing primarily in outpatient psychiatry (

n = 37, 63.8%).

Interest in PrEP Prescription

Of psychiatrists who indicated they had not previously prescribed PrEP, 53.9% indicated they would be interested in prescribing PrEP (

Figure 1A). Psychiatrists practicing primarily in inpatient psychiatry (relative to outpatient) were less likely to indicate interest in PrEP prescription (aOR = 0.43 [0.19–0.96],

p = 0.04) as were those who had completed a community psychiatry fellowship (aOR = 0.25 [0.11–0.57],

p = 0.001). Greater confidence in managing GMC (aOR = 1.30 [1.13–1.50],

p < 0.001) and PrEP‐related tasks (aOR = 1.53 [1.28–1.84],

p < 0.001) were associated with interest in prescribing PrEP.

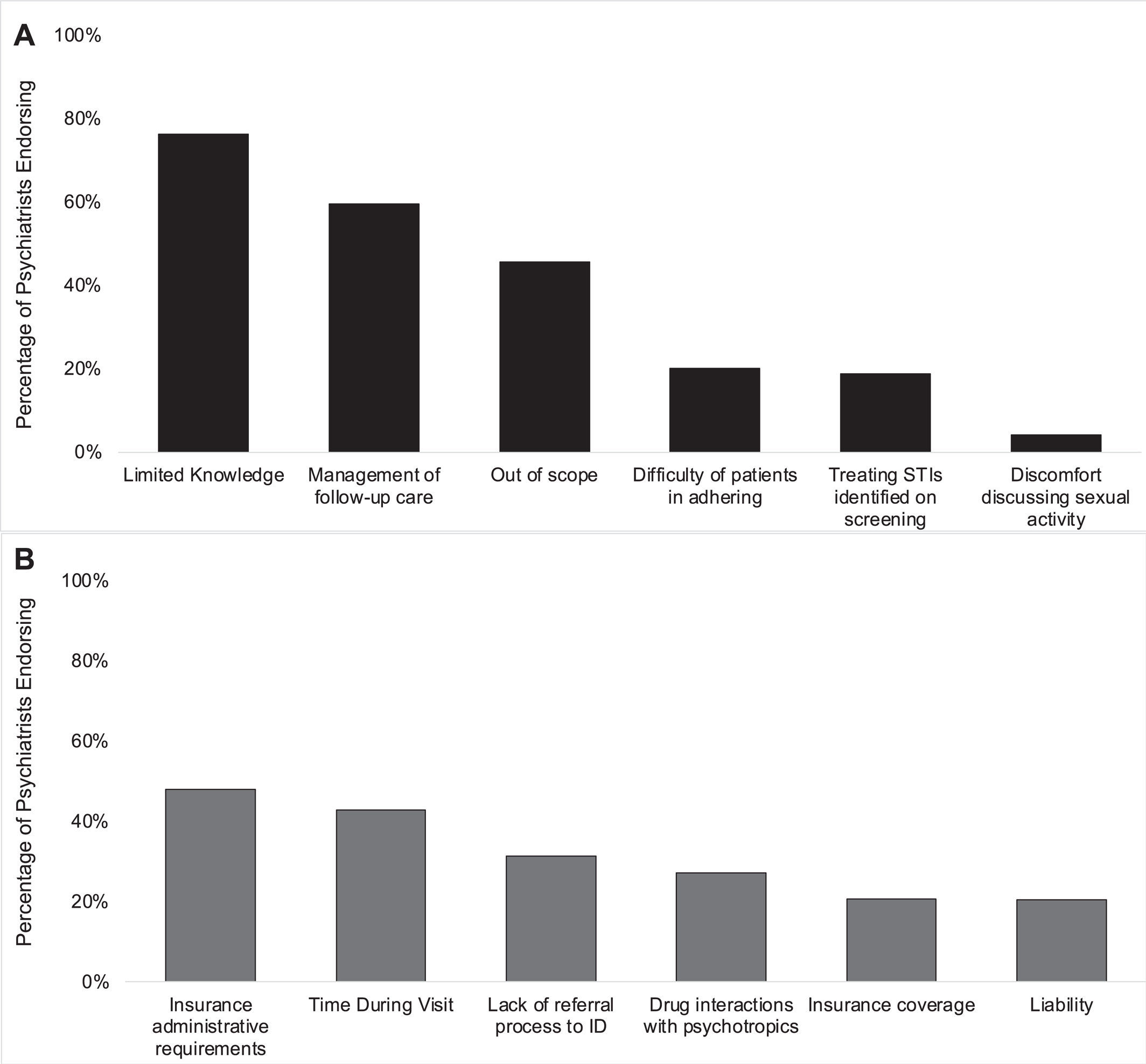

Individual & System Barriers to PrEP Implementation

All participants endorsed at least one individual‐level barrier to PrEP implementation (

Figure 2A). The most frequently indicated individual barrier was limited knowledge of PrEP (76.3%) and the least frequently indicated was discomfort discussing sexual activity with patients (4.2%). High percentages also endorsed the need to manage follow‐up care for patients on PrEP (59.5%) and the view that PrEP was outside of the scope‐of‐practice for psychiatrists (45.6%) were additional barriers.

All participants also endorsed at least one system‐level barrier to PrEP implementation (

Figure 2B). The most frequently indicated system‐level barrier was administrative requirements from insurers for PrEP (48.0%) and the least frequently endorsed was liability of PrEP prescription (20.5%). Limited time during visits to discuss both PrEP and the patient's psychiatric needs (43.0%) and lacking a referral process to Infectious Diseases for patients identified as HIV seropositive (31.4%) were additional barriers. Analysis of anticipated barriers separated by primary practice setting followed this overall trend (Supplemental Figures

S1 and

S2).

Overall, the percentages of psychiatrists endorsing each barrier were similar in the groups of psychiatrists who had prescribed PrEP following a patient request (n = 112) and who had not (n = 58) and the overall sample. Compared to those who had prescribed following a request, those who did not were more likely to endorse that PrEP was outside of their scope of practice (χ2[n = 170] = 6.93, 25.0% vs. 44.8%, p = 0.008) and that management of the follow‐up care for PrEP (χ2[n = 170] = 5.59, 46.4% vs. 65.5%, p = 0.02).

Preferences for PrEP Implementation & Training

The greatest percentage of psychiatrists (63.1%) indicated that a model in which a psychiatrist would prescribe an initial prescription of PrEP to a patient with prompt follow‐up with primary care or infectious diseases was their preference (

Figure 1B). Smaller but still sizeable percentages indicated that having all psychiatrists in the practice trained in PrEP prescription and management (55.5%), referral outside the practice for PrEP prescription (41.1%), and having a single psychiatrist trained as the PrEP specialist for the practice (28.3%) were acceptable implementation methods (

Figure 1B). Overall, 67.3% of psychiatrists were interested in receiving training on PrEP (

Figure 1B). Online training about PrEP prescription was the preferred method overall (88.7%).

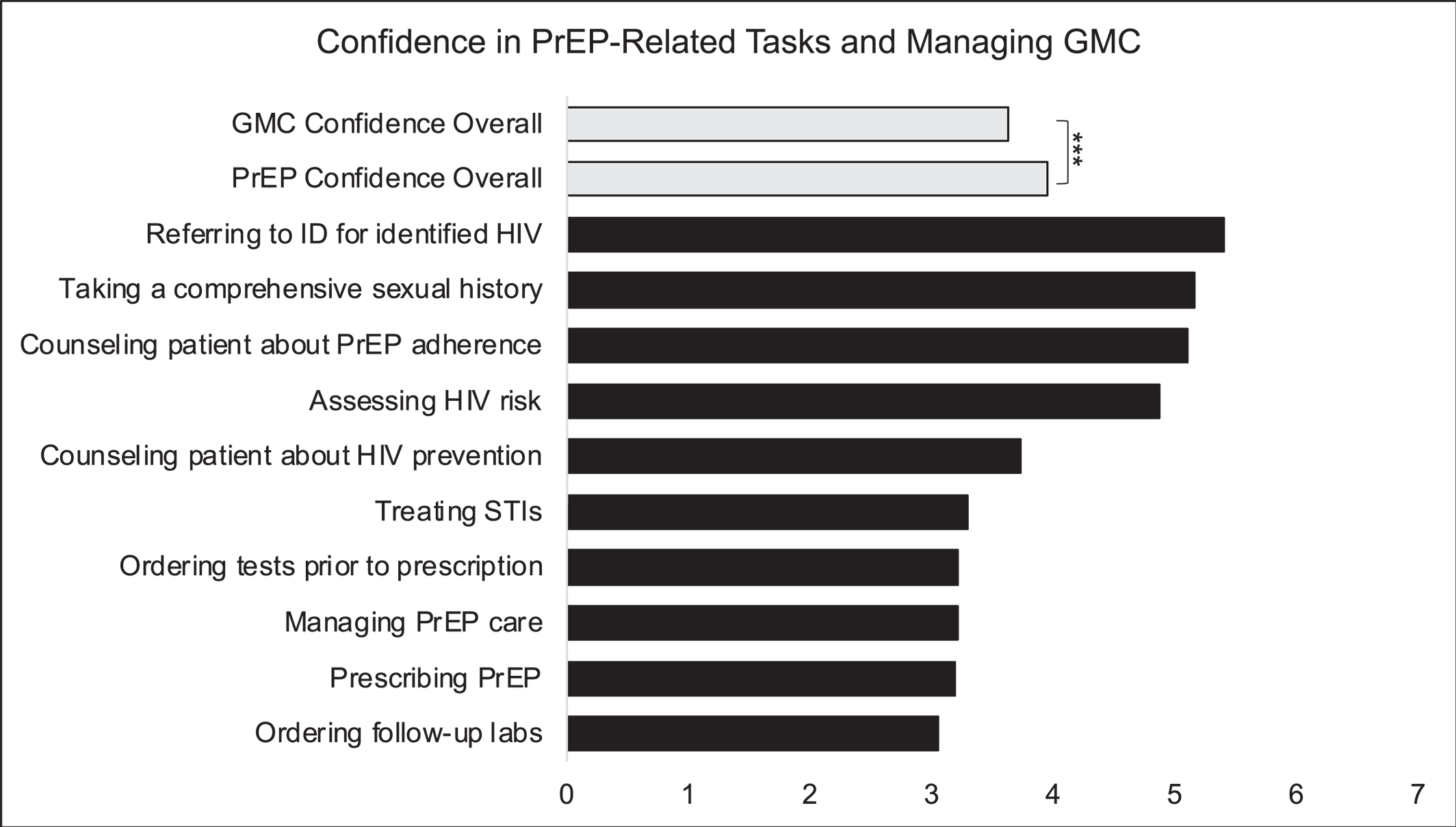

Confidence in PrEP‐Related Tasks

Overall confidence for PrEP‐related tasks was 3.95 (3.88–4.03) which was greater than mean confidence managing GMC (3.64 [3.54–3.73],

p < 0.001) (

Figure 3). Psychiatrists self‐reported the greatest confidence in referring patients to infectious diseases specialists for newly identified HIV diagnoses (

M = 5.41, [5.29–5.52]) and lowest in ordering follow‐up labs and testing for patients taking PrEP (

M = 3.06, [2.92–3.20]). Mean confidence managing GMC (

M = 4.72 [4.44–5.00] vs.

M = 3.49, [3.17–3.82],

t[168] = 5.36,

p < 0.001) and PrEP‐related tasks (

M = 5.03 [4.82–5.25] vs.

M = 4.09, [3.82–4.37],

t[168] = 5.16,

p < 0.001) were greater among the group of psychiatrists who had prescribed following a patient request compared to the group who did not.

DISCUSSION

Eliminating HIV for PLWMI will require a concerted and coordinated effort, including diversification of the settings in which a PrEP prescription can be obtained, as highlighted by the EHE (

21). Psychiatrists are well‐positioned to contribute to these efforts. In this study of predominantly psychiatrists in academic medical centers, we found that 17.3% had prescribed PrEP to a patient and that the greatest percentage of these were practicing primarily in an inpatient psychiatry context. Over half of psychiatrists were supportive of integration of PrEP prescription into their practice but noted that limited knowledge of PrEP would be a barrier, while 67.3% of psychiatrists were interested in further training about PrEP. The 2021 CDC guidelines specify a patient's request for PrEP is sufficient justification for prescription (

27). We found, approximately 35% of psychiatrists who received a PrEP request from a patient did not prescribe, representing critical, missed opportunities for HIV prevention within psychiatric care and a need for training and implementation science to improve uptake of PrEP.

Limited knowledge of PrEP was the most frequently indicated individual barrier to PrEP prescription among psychiatrists (76.3%). This finding is similar to previous studies of other clinicians (

8,

29). Additionally, large percentages of psychiatrists indicated that managing follow‐up care for patients taking PrEP was a barrier. These pragmatic elements of the clinical practice surrounding PrEP can be protocolized with concise training focused for psychiatric practice. The relative simplicity of the specific clinical tasks for PrEP management coupled with the greater relative self‐reported confidence in managing PrEP over GMC among the psychiatrists in this sample supports this possibility. In analyzing the effects of fellowship training, minimal effects were identified between fellowship‐trained psychiatrists and those who did not complete a fellowship. Among CL‐trained psychiatrists, the finding that this group was less likely to have prescribed PrEP is not surprising given the role as consultants in patient care rather than long‐term primary psychiatric providers. Interestingly, psychiatrists who completed a community psychiatry fellowship were less interested in prescribing PrEP, however this may be because they are practicing in settings with co‐located primary care where PrEP could be prescribed. Further study is needed to identify specific knowledge gaps among psychiatrists to design training and medical education initiatives.

High percentages of psychiatrists indicated administrative requirements, like prior authorization, (48.0%) and lack of insurance coverage for PrEP prescription (20.7%) would be system‐level barriers. However, this is a misconception as the Affordable Care Act mandates that most insurers provide coverage without cost‐sharing for preventive services that have received a “Grade‐A” evidence recommendation from the USPSTF, which PrEP received in 2019 (

27). Reconciling this with psychiatrists' concerns of administrative burden, perhaps influenced by formulary restrictions for some psychotropics or the utilization of Risk Evaluation and Management Systems for drugs like clozapine, may be an important factor to facilitate prescription of PrEP by psychiatrists.

We identified an important, possibly facilitating factor for PrEP prescription in the present study: comfort discussing sexual activity with patients. Discomfort in this task was the least frequently identified barrier to PrEP implementation by psychiatrists (4.20%). This is an encouraging finding as previous studies of physicians have identified discussing sexual activity and sexual health as a barrier to PrEP initiation (

30). Psychiatric care creates a safe environment to discuss sensitive subjects, such as sexual activity and drug use, and this therapeutic alliance may lend itself to conversations about harm‐reduction with HIV PrEP.

Implications & Opportunities

The science and efficacy of PrEP for HIV prevention is well‐established, but clinical adoption has not reached the necessary scale. Implementation strategies and adjunctive interventions are needed to bridge this gap to expand access to PrEP for all patients who are vulnerable to HIV (

31). Many prior implementation strategies to increase PrEP use have been reported in the literature (

31). Adaptation of existing interventions for implementation in psychiatric care may be an efficient and rapidly scalable method for increasing PrEP use among PLWMI, reducing HIV incidence in this underserved population, and addressing the system barriers to PrEP implementation reported by psychiatrists (

32).

It is notable that the greatest percentage of psychiatrists who previously prescribed PrEP practiced primarily in inpatient psychiatry (30.8%). Implementation of a protocol to initiate PrEP prescription prior to discharge from the inpatient psychiatry with linkage to PrEP navigation services upon discharge may be a promising future direction to reach patients who face other difficulties in accessing care. Such a model would align with psychiatrists' indicated preference for initial PrEP prescription with subsequent follow‐up. A similar structure has been applied in other acute care settings like emergency departments (ED) in which patients with HIV risk‐factors are referred for timely PrEP initiation as an outpatient (

33). Existing ED PrEP navigation models have not included PrEP prescription while in the ED (

33). But, PrEP prescription may be possible at discharge from inpatient psychiatry with appropriate follow‐up appointments and HIV testing arranged given that psychiatric hospitalization is longer and gives more time for care coordination as opposed to an ED visit. PrEP initiation for medically hospitalized patients with HIV risk‐factors was feasible and acceptable in a recent pilot study suggesting this may be possible in other types of inpatient care (

34).

This sort of a model may also be feasible in settings that already have some degree of psychiatric and primary care service co‐location, such as in Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) or look‐alike facilities. However, this model is not in place in all mental health care settings. Implementing a model in which psychiatrists begin PrEP with prompt referral would require identification and organization of referral streams that are unique to the existing workflows of a care setting. This sort of practice model may also limit prescription as not all patients seeking psychiatric care have established primary care follow‐up to continue PrEP prescription. Importantly, we found that most psychiatrists who'd previously prescribed PrEP had done so between 1 and 5 times suggesting prescription is not sustained. This has been identified in other studies as well reinforcing the need for interventions aimed at PrEP persistence especially with ongoing HIV risk (

35).

One such practice model may be informed by previous collaborative practice initiatives to scale the use of buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. The Physician Clinical Support System‐Buprenorphine (PCSS‐B) is a previously described model in which primary care clinicians acted as the primary prescribers of buprenorphine with a national support system of addiction medicine specialists and psychiatrists acting as a resource (

36). This arrangement may be adaptable to PrEP prescription by psychiatrists with a select group of infectious disease or primary care clinicians serving as a resource for psychiatrists who are identifying HIV risk‐factors in patients and prescribing PrEP. Such a model would allow psychiatrists to manage the day‐to‐day aspects of PrEP care, with expert availability when needed. This model may also address the identified barriers of needing an urgent referral process should a patient be identified as newly diagnosed with HIV and in treating STIs diagnosed upon screening. Similarly, the University of California San Francisco operates the National Clinician Consultation Center for HIV care and prevention‐related clinical questions as well as providing online resources about PrEP (

https://nccc.ucsf.edu/). An additional possibility is collaborative care models with pharmacists within psychiatric practice given increasing engagement of pharmacists in HIV prevention and mental healthcare (

37,

38).

Additionally, psychiatrists and psychiatric care facilities have longstanding experience with LAI antipsychotic and anti‐craving medications, including clinical services for regular administration of both intramuscular and subcutaneous formulations. LAI‐cabotegravir represents the first LAI‐PrEP option with possible approval of lenacapavir, which is in clinical trials to evaluate effectiveness as PrEP administered subcutaneously at 6‐month intervals. Implementation of co‐located service models in which LAI‐PrEP and LAI‐psychotropic or anti‐craving medications are administered at synchronized intervals may also represent an efficient way of improving PrEP uptake. Leveraging the existing clinical workflows and physical/staffing infrastructure for medication storage and administration within psychiatric care settings may also provide valuable lessons for integration of LAI‐PrEP in other clinical contexts with less experience with LAI medication formulations (

39).

Limitations

The findings of the present study should be interpreted considering several limitations. First, most of the participants in the study were practicing in academic medical centers which does not represent the full spectrum of psychiatrists and practice settings. Many patients receive mental health care in community settings or through collaborative practice arrangements which are an important target for future study to support PrEP prescription for PLWMI. Second, we intentionally oversampled psychiatrists practicing in the EHE priority jurisdictions given the significant need for additional HIV prevention focus and disproportionate incidence. However, these jurisdictions are primarily large, urban centers and thus we did not capture a significant number of responses from rural areas of the U.S. Future work should specifically focus on recruitment from rural regions which experience unique barriers to HIV elimination, especially limited prescriber availability and access. Scope of future work should also be expanded to include additional practitioner groups, especially non‐physician and non‐psychiatrist providers (eg. physician assistants, nurse practitioners, general practitioners) who comprise much of the workforce in rural settings (

40). Finally, we acknowledge the low response rate of this survey which may limit generalizability of these findings to describe PrEP prescription within psychiatric care. Data collection from physicians, while essential, is difficult given time constraints in clinical practice. We attempted to overcome this with in‐person recruitment at a large meeting of psychiatrists however still achieved a low response rate. However, our response rate is similar to prior studies of physicians related to HIV PrEP (

20).

CONCLUSION

PLWMI are at heightened vulnerability to HIV. Domestic and international HIV prevention agendas place specific emphasis on improving targeted HIV prevention efforts for PLWMI and one such way to accomplish this is engagement of psychiatrists in PrEP prescription. In this large, national study of psychiatrists, we found that a majority were interested in prescribing PrEP and 17.3% had already done so. Most participants indicated that knowledge of PrEP, time during visits, and belief that PrEP prescription was out of scope‐of‐practice were the greatest barriers to PrEP prescription. Additional research is needed to understand specific knowledge gaps and their associations with PrEP prescription. Most psychiatrists preferred a PrEP implementation model in which patients who were at risk for HIV received an initial prescription for PrEP from a psychiatrist with linkage to follow‐up care outside of psychiatry. Further research is needed to evaluate practice models to implement PrEP prescription within psychiatric practice with the goal of expanding access to HIV prevention for psychiatric patients.

Clinical Implications

PrEP for HIV prevention is an effective and safe intervention however uptake among psychiatric patients has not met the public health need of this vulnerable population. As the primary clinicians caring for people living with mental illnesses, psychiatrists have an important role in expanding access to PrEP to prevent HIV, but data to support these efforts are sparse. The results of this study suggest that psychiatrists are interested in prescribing PrEP but need training to support broader integration. Many aspects of the clinical management of PrEP prescription are protocol‐based and can be easily integrated into psychiatric care, leveraging existing workflows. Training about PrEP for HIV prevention that is specifically focused on the needs of psychiatrists should be developed to support PrEP prescription by psychiatrists to increase access for patients vulnerable to HIV.